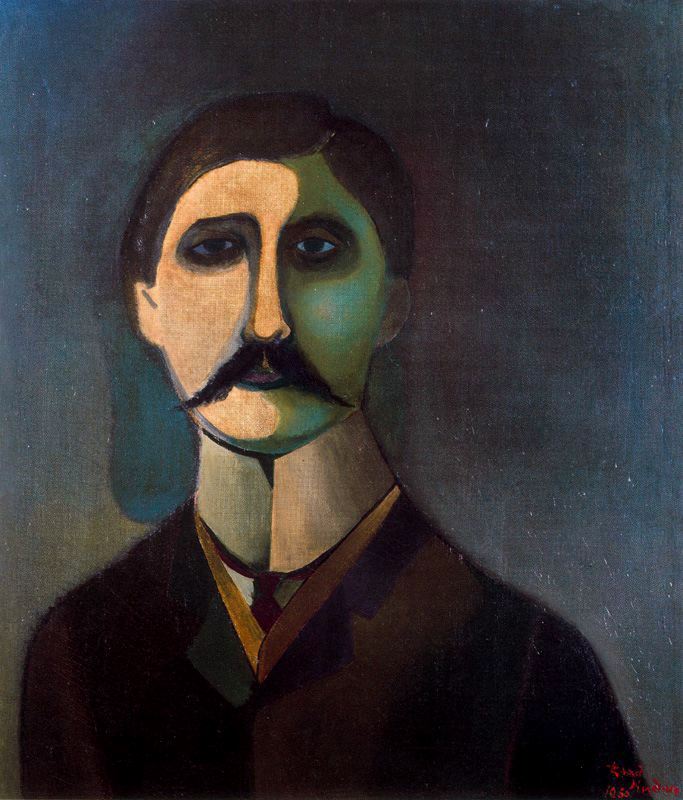

The story of Proust’s madeleine in Swann’s Way is almost certainly the most famous passage of In Search of Lost Time, a cultural export so entrenched as to be a talking point even for those who have never read a word of Proust’s enduring novel. The narrator, tasting a cookie dunked in tea, is transported to distant childhood by way of the seductive power of involuntary memory, a world unspooled from the delicate budding of a single, potent recollection. It is intensely relatable — indeed, the Proustian project, for all its intimidating length and esoteric reputation, remains warmly universal: to recapture what is irrevocably lost by time’s erosion. For Proust, remembrance is tantamount to prayer.

That act of reverie — of navigating deep, personal memory — is composed of a kind of cinematic intimacy: awash in telling detail and dramatic, curated sequencing. Memory coalesces into individual moments of charged significance and calcified feeling. They haunt the twilit attics and musty parlors of our inward worlds, untold troves of dusty stills and rickety loops. When we imagine, when we recall, we make concentrated movies of these interior spaces, a series of connected echoes.

In the production of memory, you might say we traffic in the Proustian gif.

True, Proust’s most famous of memories was one of taste, not sight. It is the madeleine dipped in tisane that plunges the narrator into deepest reverie. But in thinking about gifs — the charming, droll, undoubtedly beloved visual currency of today’s internet space — I kept returning to the dreamy-eyed French novelist and his evangelism for the intensity of memory. It seems to me that gifs — as circuits of mesmerizing imagery — are built like and analogous to a kind of invented memory, perhaps a communal one. What is a memory if not a circling, tightly wound emotional coil? If I dream in absurdist cinema, I remember in gifs.

Though ostensibly disposable, the humble gif has become a potent narrative force in web content and culture, jockeying with text and static photography for storytelling primacy. The gif, with its modest looping of a few sequential frames, has become an unlikely cultural emblem for a technologically mature world more than capable of crafting long-form, exquisitely pixel-dense video; however, the gif’s efficiency — its unparalleled ability to trim time’s messy sprawl down to easily digestible morsels of experiential visual data — has solidified its standing as a robust narrative technology. The gif isolates and magnifies. It hypnotizes. It raises mythologies almost overnight. If Venus were to emerge from her shell today, we wouldn’t turn to a Botticelli or a Wagner for cultural testimony, or at least not entirely; rather, the moment would be brief and bright and endlessly looped. The gif would give us a goddess, distilled.

But whence came this pervasiveness? Why should the gif, with its considerable formal constraints, become such a ubiquitous narrative language? Certainly its technological pedigree of broad support and easy portability has played an enormous role in its proliferation; however, I think there is something else at work here, a lurking significance inherent to the format itself. The gif, for all its supposed inconsequentiality, is endlessly meditative. Whether composed of Beyonce’s mugging, a chemical reaction, or the last moments of a human life, gifs offer a unique opportunity for extended contemplation of a single phenomenon. There is an addictive brevity at the heart of the gif that appeals to our habituating brains. Given the informational cacophony of internet space, rife with click-baiting dreck and the relentless blare of image curation, it is a real (and rare) satisfaction to home in on something intensely focused, something that delivers what it promises — a singular, lean study of slivered time.

And that, to me, feels an awful lot like a sort of Proustian shorthand. Implicit in any attempt at chasing time is the search for a commensurate means of capturing it. Siegfried Kracauer, that great chronicler of mass culture, wrote about the intensification of time in personal memory, a process of enlargement by which, often inexplicably, the ephemeral is revealed to contain as much potency as the permanent. He called these crystallizations “monograms”, and I believe the allure of the gif is tied up in something similar: its ability to intensify, to concentrate, to repeatedly articulate an otherwise fleeting essence. The gif, in subverting time’s decay, however modestly, speaks to the larger aims of any representational art — namely, to capture the warp and woof of shimmering, prismatic reality.

That it does so in such an economical fashion seems to me not a mark against it, but rather a fascinating adaptation necessitated by a perennially distracted world. Walter Benjamin said that memory collapses time. A useful analogue to this statement might be that technology collapses form. This, to me, is not something to wring one’s hands over. I shrug off the shrill decrying of technology as the killer of high art. It will take much more than a knee-jerk Luddite’s saying so for Twitter to slay the novel. But that is not to say all forms are equal — nor should they be. The gif, like Twitter, serves us best as a scrappy supplement to the more holistically engaging forms of the novel or the art film. It fills in small sociological blanks; it shines a miniature beam of light upon a particular fascination or jest or human frailty. In the end, the gif is found most happily in the gaps.

According to the Futurists, it is an inevitability that consciousness and the plumage of memory will someday become digitized, transformed into fields of multi-sensory data. One imagines Proust reliving what he termed the “precious essence” in an ecstasy of reverie, at last able to wring every exquisite drop of nostalgic pleasure from a bank of endless memory. What would that collection look like? Bundles of circuitous pain and love, tiny parcels of beauty, a bright and breathless assortment of lusts. Strange treasures, these — inward gifs, in a sense, yet enhanced, enchanted. The gif, as a miniature model of specific experience, can be seen as a first faltering step towards a kind of tech-utopian vision of a digitized Emersonian Over-Soul: collectivized populist perception as a mapping of cultural memory.

Richer and subtler than reckoning or summation, memory, like the gif, holds no claim to completeness, or, for that matter, truth value. It is a mode of consciousness only insofar as it is a language: the soul’s private tongue. But within these strictures, memory remains the ne plus ultra of experiential artifacts, a record of impossible texture and intimacy. In Proust’s immortal novel, we find an aesthetics of memory. In the gif, however inchoate, however enigmatic, we may have been given the rudiments of its technology.

This post may contain affiliate links.