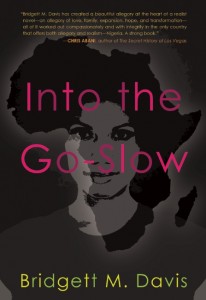

[The Feminist Press; 2014]

[The Feminist Press; 2014]

Bridgett M. Davis’ new novel, Into the Go-Slow, considers the uneasy stasis of a life mired in memory. Four years after the sudden death of her sister in Nigeria, Angie remains unable to move forward with either her grief or her life. Into the Go-Slow portrays a middle class African American woman’s experiences in both Detroit and Lagos in the mid 1980s as she tries to find herself by retracing the steps of her deceased sister. Although it is fictional, the text draws on the author’s own experiences of Nigeria in the 80s lending it the air of a textual time capsule, rife with headlines and hit songs.

The novel starts out strong, the narrator feeling like an extra person sitting at the kitchen table in Angie’s family home where global news is casually interspersed with everyday life. Once Angie heads to Nigeria (or “as far away from Detroit as you could get”), however, the plot slows down and the drama speeds up. The novel whirs from one character to the next without giving enough time for each to become much more than a caricature. Each scene is interesting in itself, but the novel begins to read like a picaresque in which every character stays rooted to the place where Angie finds and leaves them. The final scenes gush over the edges of the page without it being clear to this reader how the characters’ actions fit with their previous, albeit developing, personalities.

And, yet, there is still something powerful about this historical novel that is itself about being stuck in the past. How can we keep connections to the past without becoming trapped by it, it asks?

Following a trail of names and places mentioned in her sister’s letters, Angie scours the residue of the past for a way to understand, accept, and move out of the gridlock. The writing moves deftly between Angie’s childhood memories and young adult explorations, emphasizing how entangled we all are with what has come before, both individually and collectively. Over the course of the novel, Angie reads both Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude. Although Davis’ text incorporates none of the haunting or magical realism that characterizes these works, it does approach similar themes of being unable to move forward from a traumatic history. Throughout, Davis writes with a profound, apparent appreciation for the many writers who have shared their words with the world and demonstrates the importance of these texts in shaping her characters’ lives.

Music, too, permeates the pages of this otherwise straightforward text. Lyrics of Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson echo from the TV sets of Lagos, while Fela Kuti sings as much from Angie’s American cassette player as he does from his post-coup Nigerian club. Davis emphasizes how the words and visions of these artists permeate everyday life — the sounds of revolution and possibility. Into the Go-Slow repeatedly inspired me to wander YouTube to hear the soundscape it so carefully creates. As someone too young to remember the 80s, I found the novel’s primary interest came more from this precise recreation of an era and its voices than from its simple, memoir-like style.

Davis also tunes into the shifting dialects of its characters to illustrate the constantly changing place and class of the people Angie encounters. As Angie’s mother tells her, there are innumerable ways to be black, a statement that the novel’s almost entirely African-American or African cast illustrates well. Given its transatlantic setting, Into the Go-Slow is particularly interested in the cultural exchange between Americans and Africans. At times, the contrast is between black and white American impressions: “Later, when the May issue of Ebony came out, the cover photo boasted Africans dancing in white billowy costumes, beating drums, smiling wide, looking like exuberant, self-possessed cousins of those found in National Geographic.” At other points in the novel, the contrast is within Nigerian communities. Angie observes “the dissonance of desperate living beneath a sprawling, modern construction,” a sight that “disturbed Angie, fractured her senses.” Ultimately, perhaps her senses must be fractured to incorporate the many realities that they encounter.

By avoiding a convoluted plot and overwrought prose, Into the Go-Slow effectively highlights the difficulty of understanding the world’s many contrasts and contradictions while remaining extremely approachable. Davis’ coming of age narrative offers a needed contribution to the collection of stories that discuss the challenges of finding oneself amid all those who are already present.

This post may contain affiliate links.