[Itna; 2014]

Tr. by Vitaly Chernetsky, Margarita Shalina, Dmitry Gelfand, and Alex Cigale

Three faces of young men in uniform — they could be regular soldiers or navy soldiers — deface into ravenous wolves.

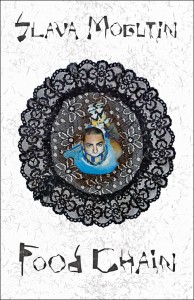

“If you’re afraid of the wolves, don’t fuck in the woods” a Russian proverb wisely recommends on the opening page of Food Chain, Slava Mogutin’s collection of poems, drawings, and pictures. The book is a retrospective collection of texts written from the 1990s to the beginning of this decade and translated from Russian for the first time. After reading the whole thing, I had the feeling that it was already somewhat encapsulated in those words: the wolves, the woods, and the fucking.

The title sets the tone and the atmosphere. The omnipresent topic of Mogutin’s work, both verbal and visual, is the encounters between young and less young men who first meet, then have sadomasochistic sex, physically and psychologically hurt each other, then laugh at each other, all while producing and exchanging a considerable amount of bodily fluids. The images and poems of the book unsubtly remind us of food chains in various ways: the texts constantly mention human bodily waste; all encounters are regulated by uncontrollable desires; the characters occupy the position either of dominating eater or eaten subject as it was assigned to them via a deterministic rule of nature that is unmediated and necessary. Bodies constantly transform, and experiences and pieces of stories imply complex and often unsuccessful digestive processes, smells and feral instincts. Mogutin’s food chains are not entirely linear, though; eater and eaten easily swap places so as to short circuit the transaction and seal the metaphor of sadomasochistic love.

The ecology of sexual appetites that constitutes the book is intertwined with the author’s personal history and, indeed, the volume describes his experiences as aspiring model, writer, and artist. Mogutin made a name for himself as a queer poet in Russia, where his publications garnered him official condemnation and two criminal cases. He then sought asylum in the United States and joined the New York City art scene, pairing his writing with other forms of artistic production, mainly photography.

Needless to say, this imaginary ecology is populated with the main icons of Russian masculinity: the training soldier, the KGB agent and his depraved son, blonde algid naked machos waving guns and taking pictures of themselves, astronauts flying high in space and losing their minds, muscled men in uniform who hide the kinkiest fantasies and then drink their lives away. This disparate collection of male characters parades through the author’s stories, but none of them ever gains depth, to the point that they could all be the same person in different circumstances or at different stages of life.

Needless to say, this imaginary ecology is populated with the main icons of Russian masculinity: the training soldier, the KGB agent and his depraved son, blonde algid naked machos waving guns and taking pictures of themselves, astronauts flying high in space and losing their minds, muscled men in uniform who hide the kinkiest fantasies and then drink their lives away. This disparate collection of male characters parades through the author’s stories, but none of them ever gains depth, to the point that they could all be the same person in different circumstances or at different stages of life.

The collection alternates poems, which roughly grow longer into more prose-like texts over the course of the collection, and images. These are mainly photographs, collages, drawings on cut-out papers with occasional snippets of writing.

Much of the visual content works via odd juxtapositions of pictures and texts that ironically contradict each other and show the internal fragility of apparently solid masculine types. In the first half of the book, a full-page image of a young Russian soldier appears under the banner: “The new action heroes.” The caption at the bottom of the photo goes: “We Must Expand Our Nuclear Power Program If We’re To Realize Our Dreams Of Superhero Mutants.” The man has a fierce patriotic look and a neat face with handsome and smooth features that appear almost feminine.

The tone of the book is sarcastic and, at least in the first part, also funny. Perhaps it is because the stories are stranger and the protagonists less human and, apparently, more invented and adventurous. Poetic texts uncover uncomfortable desires of hurting, beating up and shooting guns and maybe even jokingly aiming at somebody, while leaping into the absurd. Ambiguous characters, like the members of the boy-family, are as cute as they are violent and iteratively hurt each other with candid smiles on their faces. Actions are intentional, but nobody is to blame for them. Arguably, if the absurdity of certain combinations and actions helps make them more acceptable, this may speak to some degree of efficacy in Mogutin’s work at catalyzing the readers’ potential sarcasm.

As the book continues, descriptions of sexual intercourse become more explicit. Impossible lovers are carefree and ironic and have no concerns of mixing together all the stuff that material life is made of, including romance, vomit, and golden pendant crosses. If we look a layer below the apparent cynicism, we may find a sort of unstable matter of reality in which fantasies run free — and my mind, almost predictably, did briefly go to Georges Bataille while reading — and that Mogutin tries to manipulate in order to magnify odd close encounters. The point is that such manipulation loses its spark pretty quickly.

The stories of sexual intercourse, sadomasochism, and sarcastic lovers repeat each other over and over. The main pitfall of the book is very similar to the main problem porno generally has: after a while, it becomes predictable and boring.

The challenge of reading the book through to the last page, enduring my boredom, prompted a number of thoughts on the difference between monotony and actual boredom. Any sexual act implies a repetition of gestures and words. Eroticism is exuberant while being somewhat scripted. It strikes a skewed and fantastic relation between rootlessness and coded steps. New excesses break the rule, but just to be integrated in the ritual for the time to follow. Something that plays a crucial part is probably automated body rhythm, cadence, and the small inventions that syncopate the movement.

When translating erotic sadomasochistic intercourses into words, the sensual experience is obviously limited, but the problem of Mogutin’s erotic writing is that the rhythm flattens out into boredom. The pace shows no minor differences or playful syncopation.

The book turns into an amorphous avalanche of anal penetrations and blowjobs, in which terms related to quantities begin to stand out as in every predictable and safe porno: the sperm projected onto somebody’s face is always a generous unload.

This does not necessarily mean that the radical intentions of Mogutin’s writing are entirely evened out due to limited inventiveness or a lack of — alas — eruptions. But ultimately they are tamed, and just a little less queer than we would like them to be.

Silvia Mollicchi is a writer, co-founding editor of Fungiculture, and is currently based in London.

This post may contain affiliate links.