[Counterpoint; 2014]

[Counterpoint; 2014]

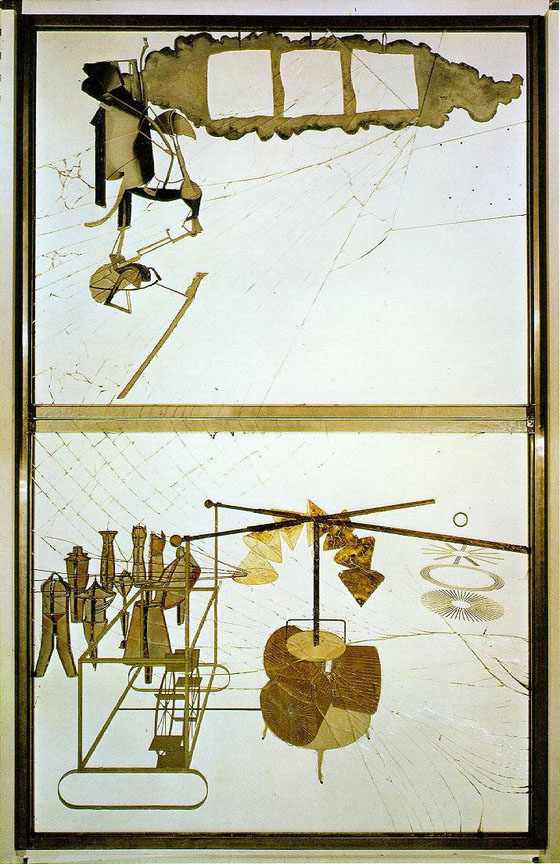

The tension at play in Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even is the result of temporal paralysis; by virtue of being an inanimate work of art, it obscures the movements of the complex machine it depicts — a machine whose movements would likely clue us into its meaning. It’s divided into two panels — a masculine and a feminine, with the feminine “bride” object — a mechanical, relatively genderless Chihuahua-esque thing that, were it not for Duchamp’s vivid title and published notes, wouldn’t exactly scream femininity — suspended over a clusterfuck of “bachelors” — knobby, dwarfed “malic molds” hooked up to an apparatus with a chocolate grinder at its core.

In her isolation and her longitudinal superiority, the bride appears at once almighty and encaged, objectified through glorification. It might seem that “The Bachelor Machine” — the phrase Duchamp coined for the male, bottom half of the piece — runs on the sustenance of the bride’s image. But on the flip side, it might also seem that the bride’s image is projected from The Bachelor Machine, her being only actualized by male longing. We’re left to speculate on what, in Duchamp’s eyes, is causal and what’s consequential — that’s why the piece is so haunting. Just as the placing of dehumanized shapes on view in the piece sums up gender relationships in a tableau of perpetually unfulfilled desire, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even is, for the viewer, a flagrant perpetrator of intellectual blue-balls.

In her isolation and her longitudinal superiority, the bride appears at once almighty and encaged, objectified through glorification. It might seem that “The Bachelor Machine” — the phrase Duchamp coined for the male, bottom half of the piece — runs on the sustenance of the bride’s image. But on the flip side, it might also seem that the bride’s image is projected from The Bachelor Machine, her being only actualized by male longing. We’re left to speculate on what, in Duchamp’s eyes, is causal and what’s consequential — that’s why the piece is so haunting. Just as the placing of dehumanized shapes on view in the piece sums up gender relationships in a tableau of perpetually unfulfilled desire, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even is, for the viewer, a flagrant perpetrator of intellectual blue-balls.

But a novel — at least a traditional novel — moves. Quite obviously, it travels through time, and in reading, one becomes aware of its machinations and forms a clearer idea of who’s doing what to whom. The “readymade”-titled The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, by Chris F. Westbury, being a conventional novel, follows suit: in it, we see a man with severe OCD (which fuels his obsession with Duchamp) slowly begin to understand himself and transcend the confines of his mental illness. Somehow, despite its themes of death and mental illness, the book turns out to be a sweet, lighthearted comedy — albeit one that’s choked in decorative philosophizing (between two art history buffs and a women’s studies doctoral candidate, Westbury creates characters who can spout philosophy so that the novel as a whole doesn’t quite have to).

The recognizable road-trip-comedy format — a heartfelt romp where people overcome internal obstacles while dealing with the obstacles of the great American road — here diminishes Duchamp’s work by asking it to fit into its well-mannered story of personal betterment and healing. The book is written from the POV of Isaac, whose OCD makes him experience art as a form of compulsion (he can spend months revisiting the same painting at the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum daily). He and Craig, a friend from his OCD support group, meticulously plan a trip to the promised land — Philadelphia — to visit The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, engage in a relatively futile meta-“performance art” piece about the Bride, and buy a chocolate grinder akin to that in the piece. Of course, given that their OCD precludes them from doing most things they’d need to do to get from one city to another, they hire the crushingly beautiful grad student Kelly to drive them in their disinfected rental Winnebago.

Despite its philosophizing dialogue, the book seems at times old-fashioned, especially when dealing with gender. Due to their germophobia, the two protagonists are extremely wary of touch — this symptom has understandably led to romance-free lives. In this regard, Westbury’s characters are the ideal parallel to the bachelors in Duchamp’s piece — inert men who look but cannot touch. This could be the author’s chance to show the more unsettling results of repressed male sexuality, but this book and its protagonists are far too good-natured for that. As such, there’s dissonance here between the Duchamp piece and the novel — Bride the book is a cute story whose themes seem naively fleshed out by Bride the work of art with far more disturbing connotations. Westbury problematically characterizes the two female romantic interests by their beauty and exoticism, seeming to uncritically fulfill what Duchamp might be critiquing in the way men relate to women. The laws of hackneyed rom-coms dictate that the woman HAS to be beautiful — is this not a rule that perpetuates the spinning of the bachelor machine (if, indeed, said machine spins)?

Westbury’s best move here is the juxtaposition of OCD and Duchamp’s perfectionist reevaluation of societal “givens”: the book’s two “diagnosable” protagonists are plagued by crippling compulsions — acts that, on their own, may seem nonsensical, but serve as a physical proxy for more abstract obsessions — hand washing, obsessive counting, making sure to always park in a specific direction. The rigidity of the way they run their everyday lives (through a series of illogical gestures and actions that, in their heads, provide some form of comforting logic) mirrors the precise architecture of Duchamp’s semi-abstract shapes in The Bride, and the way they coalesce into an enigmatic, but possibly logical entity.

Despite this connection, Westbury’s reading of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even ultimately proves narrow. Tapered off by a rushed marriage plot, the book offers an old-school reading of the work of art: the guy gets the girl, and the boundaries between male and female are shattered! Male longing is fulfilled! The female is brought down off her pedestal and into a happy union! In Duchamp’s piece, we’re presented merely with a frozen moment, and because of that, we’ll forever be unaware of the endgame of Duchamp’s gendered spatial relationship, and unaware of any meaning beyond its delayed potentiality. Sadly, this is a teleological novel. From the start, it seems a story bound for a happy ending. Imagine Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even if the bachelors and bride had transcended the boundaries of their respective glass panels, and were living happily ever after in Philly. I don’t know if I’d travel to Philly to see that.

Moze Halperin is an almost-Brooklyn almost-playwright and almost-author. He likes ham (from time to time).

This post may contain affiliate links.