[McSweeney’s; 2014]

Inventive and hilarious, The Parallel Apartments delights in the oddities of people and language. Inhabiting a mesmerizing and unnerving kaleidoscope world, Bill Cotter’s vivid characters turn “extreme” into the new normal. In this bizarre, yet consistent universe, a bullied-child-turned-sociopath lives next door to an opera singer whose psychotic desire for a child drives her to actions even Wagner wouldn’t stage. Cotter’s novel is remarkable in the sympathetic attention it gives to its characters, no matter what their motivations. By allowing these drives to play out, The Parallel Apartments holds true to the world it has created, even when it leads to brutal results.

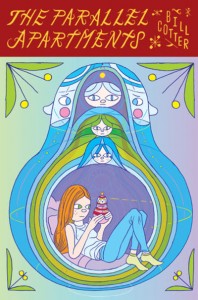

The book primarily unpacks the estranged, lie-ridden family of Justine Moppett. Like a set of Russian nesting dolls, the women in Justine’s family contain multitudes. Shifting between the stories of Justine, her mother, and her grandmother, The Parallel Apartments considers how people perpetuate themselves in both their offspring and their stories. The female characters dominate The Parallel Apartments, each obsessing over the possibility of pregnancy. Most of the novel’s women try desperately not to become pregnant, using everything from an ill-advised triple layer of condoms to a blessedly infertile sexbot as preventive measures. The novel’s title, then, does not just represent the intertwining lives of several unusual tenants in the Parallel Apartments complex. It also describes the parallel lives of one person growing inside the body of another. Unlike most parallel lines, however, these lives repeatedly, bizarrely, and dramatically intersect.

A novel so preoccupied with pregnancy naturally depicts a lot of sex. So much sex, in fact, that if thinking of sex every seven seconds is your m.o., this novel will not inhibit your habits. In fact, the scenes that don’t involve sex in some way are glided over. Without ignoring the reality of nonconsensual interactions, The Parallel Apartments offers a kinky, sex-positive approach to life. Although admirable in its determination to avoid heteronormative representations of sex, The Parallel Apartments’ portrayal of all women as pregnancy-obsessed and almost all men as incapable of forming lasting, monogamous relationships is frustratingly stereotypical. Only the character who is both male and female proves a consistently functional partner and parent. These polarized depictions illustrate the dysfunction of limiting people by their sex or gender, but the novel’s composition does not sufficiently prevent these stereotypes from feeling reinforced rather than undermined.

A novel inhabited only by extreme cases, it still manages to feel real with descriptions of people acting like people, as when Justine (a child at this point) tries to find out about her mysterious grandfather:

“Who’sLouWho’sLouWho’sLouWho’sLouWho’sLouWho’sLou?” Justine had said while lying in the middle of the kitchen floor dressed in a Little Orphan Annie costume, its curly red wig component wadded up and stuffed under the smock component in order to create a bosom component, which Justine felt essential for her interpretation of the character.

Young Justine’s sexualization of her character parallels the way Cotter prioritizes sex for his characters. But, given Cotter’s penchant for descriptive lists, his characters do not lack for other qualities to supplement their sexuality. By stringing together a host of attributes, Cotter prevents his reader from assuming which traits reside together. For example, describing Sousou, a character who barely stays in the story past her initial description, Cotter writes:

Cynical, gloomy, lazy, promiscuous, larcenous, well read, forgetful, brilliant, nippy, sexy, unhealthily crushed out on Bob Newhart, betrothed to a local Satanist, tattooed from earlobe to instep with wandering particolored scrolls and long vines of mysterious rhetoric that crept beneath the cuffs of her cutoff overalls, then emerged from under the collar of her T-shirt and circled her neck a few times before disappearing into the hairline behind her left ear . . .

I recommend The Parallel Apartments with a warning: it is occasionally graphic in its horrors as well as its pleasures. I laughed aloud more than once, but I also had to close the book at one point to stem my nausea. The novel quickly shifts between wittily entertaining scenes and intensely disturbing ones. Ultimately, The Parallel Apartments is much like the set of Russian nesting dolls on its cover: charming, but also all-too-similar and uncomfortably trapped within itself.

Emma Schneider is a graduate student at Tufts University; her research focuses on North American and Environmental Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.