Music, awake her; strike!

‘Tis time; descend; be stone no more; approach;

Strike all that look upon with marvel. Come,

I’ll fill your grave up: stir, nay, come away,

Bequeath to death your numbness, for from him

Dear life redeems you.

—Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale

There was always something extra-dimensional about Martin Scorsese’s filmmaking. Take the synaesthesia of the opening sequence of New York, New York (1977), the V-J Day celebration in 1945 with its dizzying crowds and Big Band sound and popping colors. Scorsese designed New York, New York to look like a series of realist and expressionist paintings come to life in the way only film, with its kinetic movement and immediacy of lived experience, can achieve. Hugo (2011), Scorsese’s epic fable shot in 3D, is a painting come to life in the second degree. You can see Scorsese using 3D technology as an extension of film just the way he used film, in 1977, as an extension of painting. Along with Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), Ang Lee’s Life of Pi (2012), and, this year, Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013), Hugo is one of the great marvels of this early era of 3D because it uses the technology as an artist’s media, not a parlor trick or commercial ploy. In Hugo, 3D also becomes an expression of the film’s subject. The story of a young orphan boy who rediscovers the magical films of Georges Méliès in the years after most of them were destroyed during the Great War, Hugo is a fable of renewal and rebirth. It allows us to see the world’s first films, like the Lumière Brothers’ short picture of the train arriving in the station, as though we were among the world’s first audiences: through 3D we experience them as astonishingly, dazzlingly new. Méliès was a magician-turned-filmmaker, and in Scorsese’s hands 3D is the new magician’s art, one that mediates between the photographic real and the illusive imaginary.

Hugo is actually a film about the conceptual continuity between the invention of motion pictures and the 3D cinema of today. The orphaned son of a clockmaker, Hugo lives in Paris’ Gare Montparnasse train station, each day winding the clock in the majestic clock tower where he sleeps. He has inherited, from his father, a broken automaton, one of those wind-up toys made in the image of a human being that were so popular in late nineteenth century France. This metal machine, small and lean like a boy of eight or ten, is poised with a pen – it appears to be able to write – but it languishes inert with its head bowed; Hugo is determined to fix it up and make it run again, to give it purpose by giving it motion. To do so, he swipes wind-up toy parts from a shop in the train station run by a severe old man (Ben Kingsley) his adventurous goddaughter Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz) calls Papa Georges. Papa Georges catches Hugo one day and, after demanding that he empty his pockets, discovers the notebook full of his and his father’s sketches for the automaton. Visibly disturbed, he confiscates it, and Isabelle becomes Hugo’s ally in retrieving the notebook – Hugo’s only link to his father aside from the machine itself – and uncovering the mystery behind the automaton. For it turns out that Isabelle wears around her neck a heart-shaped key given to her by her godmother that unlocks the elaborate clockwork of the machine. And when they wind the key in the lock, they learn that the automaton does not write a message but draws one instead – a picture of a rocket penetrating the eye of the man in the moon, signed with a flourish by one Georges Méliès. (“That’s Papa Georges’ name,” exclaims Isabelle.)

The two children are connected by a mysterious past of strange inventions, by clocks and pictures and machines that come to life, and in their adventure-quest for the story behind Méliès’ picture they discover the old man’s past as a magician of moving images – one of the forefathers of cinema – a history buried by the devastation of the Great War. Méliès, like the automaton, has fallen into disuse. And so the boy who lives inside a clock discovers, through a boy that is a clock, the secret history of motion pictures as well as cinema’s special power: to transform the mechanical into the living, to awaken the dead, to bring the past back to life.

Hugo is an adventure-quest and, like Shakespeare’s late plays such as The Tempest and The Winter’s Tale, a romance – a magical tale of rebirth. What distinguishes the romance from the fairy tale is that the proper subject of the romance is reality. At the beginning of romance, the world is broken – the hero’s quest is to heal that world, often through enchanted means. Magic is not a retreat from reality but the only medicine for what ails it. Like one who disappears into the darkness of a movie theater only to discover when he emerges that the illusory enchantments of the screen have strengthened his relation to his own life, the hero of romance heals reality by recovering its hidden link to a magical sphere.

In Hugo, it is the recovery of Méliès’ films that effects this world-renewal – the old man Méliès finds his purpose, as does the boy Hugo, who becomes adopted into the family. But here Scorsese is canny, for in this picture it is not really the spiritually impoverished, fragmented world of post-war Paris that is truly in need of transfiguration. It is ours. Scorsese reaches out to an audience made so cynical and complacent by the last century of movie culture we’ve lost our connection to film’s almost primal power. The magic trick of the film is to retrieve a lost world of images through a new world of images, and to restore, in the process, the proper role of movies as realist illusions.

“Movies are miracles to Scorsese,” Kevin Courrier wrote last year in Critics at Large, “and in Hugo, he takes the wonders of technology and infuses it into the picture with an ephemeral passion that reminds us that …it was technology that enabled magicians like Méliès to become great film artists.” Hugo traces a history of movie technology, but it also gestures towards something far more elusive and far-reaching: a modern history of the desire for pictures that come to life. For moving pictures were an idea long before the invention of the Lumière Brothers’ pioneering film technology – an idea that artists, whether through celluloid or digital 3D, continue to seek to fulfill. The film critic J. Hoberman has written extensively about this new era of digital filmmaking and computer-generated imagery which he called in a piece for The New York Times Review of Books last year a “radical impurity” in film’s otherwise overwhelmingly consistent hundred-year history. But looking back on a history of film that arguably begins – as Scorsese proposes in Hugo – with magic tricks and optical illusions instead of photography, I’m not sure movies had so much purity to begin with. Georges Méliès’ place in the history of movies reminds us that the camera, like all technology, may not be an artistic end in itself but simply a means to a better kind of magic trick.

****

If the story of film is the story of the relationship between technology and wonder – the story of a magic trick that brings pictures to life – then when does that story begin? And how? My history of moving pictures begins a full century before the Lumière Brothers sent a trompe l’oeil train rolling out into the movie theater. It begins, even, before Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot, our mid-nineteenth century pioneers of photography, fixed images from nature on paper, copper and glass. Our curtain opens on Paris, France circa 1796. The French Revolution is well underway, France is at war with Britain, and the Belgian painter and physicist Etienne-Gaspard Robert is entertaining feverish visions of a new invention.

Robert’s scientific imagination was indistinguishable from his taste for drama. Earlier that year, he had met with the French government and proposed for their military a colossal mirror that, by reflecting the sun’s rays, could set the British fleet in flames. His blueprint – based on a description from the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes – demonstrated his fascination with optics, a field of physics concerned with the nature of light. By the time the French rejected his Archimedean mirror – for any number of reasons, one can surmise – Robert was already preoccupied with a new project, one that would take his penchant for showmanship into its natural arena: the world of entertainment. Rather than use reflected light as a weapon, he would use it to dazzle, to dupe and to terrify – to inspire wonder.

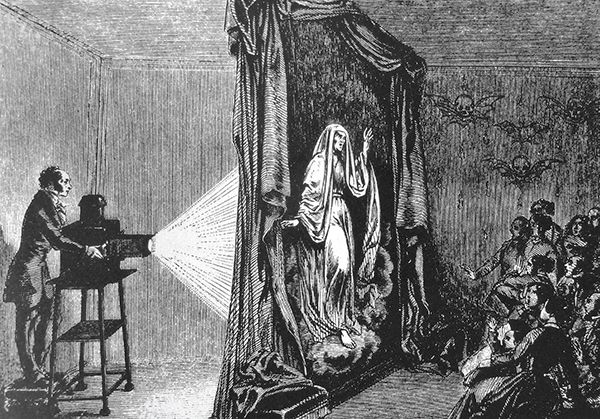

What Robert had in mind was a Gothic theater of moving images. Using a technology known as the magic lantern, he would project bright, translucent images of ghosts and demons of darkest imagination onto a dark screen made invisible by an unlit theater. The magic lantern device contained a candle and a convex mirror; a tube with a convex lens at each end held a small image painted on glass that could be reflected, magnified and illuminated. A few attachments manipulated by levers and rollers could increase the size of images, so that they appeared to move by their own volition, growing nearer and nearer to the audience. It would be like one of Fuseli’s horror paintings come to life, his succubus that clings to the sleeping maiden bounding out of the frame to menace the unsuspecting viewer – not only a new kind of painting but a new kind of magic show, a grand spectral haunting. In 1798, in an underground theater at the Pavillion de l’Echiquier bedecked with Gothic décor, he premiered his performance under the name “Robertson,” his new showman’s moniker. The show itself he called the phantasmagoria.

The phantasmagoria thrilled and terrified audiences; it was an instant sensation. Like modern viewers at a horror movie, most nineteenth century patrons of the phantasmagoria had a rough idea of how the illusions were generated, but they remained transfixed all the same. “I could never look at it without having the back of the chair to grasp, or hurting myself to carry off the intolerable sensation,” recalled the writer Harriet Martineau about the phantasmagoria. “It was so like my nightmare dreams that I shrieked aloud.” In an earlier account, recorded in Fulgence Marion’s 1871 The Wonders of Optics, an audience member attests: “A decimvir of the republic has said that the dead return no more, but go to Robertson’s exhibition and you will soon be convinced of the contrary, for you will see the dead returning to life in crowds.” Many believed they were witnesses at actual séances. A man asked Robertson to contact the woman he had once loved, and when the magician cued up a stock lantern slide of a woman, a second man ran screaming out of the theater believing it to be his wife come back to haunt him from beyond the grave.

Charles Dickens, an admiring profile of Robertson written two decades after his death, described him as “an artist in ghosts,” and truly the phantasmagoria was a ghost art, an art of symbolic resurrection that used the power of visual imagination to awaken the dead. Even the invention itself was a sort of ghostly return: it resurrected the physicist Robert as the magician Robertson, and the art of painting as the art of moving pictures, a transformation effected by optical science combined with an early intuition about the dark workings of what Freud would later call the unconscious. For Robertson’s moving images did not excite the audience by showing them what they had never yet imagined. They excited the audience precisely because they visualized their most private fantasies and fears. Like our dreams, successions of real and illusory images and states, the phantasmagoria was not in essence pure fantasy. Its power was in the liminal space it created between the fantastical and the real.

****

In Hugo, the past is resurrected to heal the broken present. Cinema is an art of magical restitution, of recovering what was lost or buried or dead. But in Robertson’s phantasmagoria, the dead were awakened with no healing in sight. The phantasmagoria was the dark underside of the romance, where ghosts and specters haunt the living without redemption or mercy or promise of spiritual renewal. It was not only the morbid subject matter of Robertson’s phantasmagoria that gave it the appearance of necromancy. It was the effect of the images themselves. Surging, changing, dissolving in endless transfiguration, they seemed to represent a symbolic return from the dead, one in which the boundary between the real and the illusory could be indefinitely suspended. Robertson’s great contribution was his recognition that spectral images – projections with no substance or tangible form – could mimic the intensity of imagination and dreams.

Robertson’s magic lantern show was only the beginning. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the phantasmagoria traveled across the English Channel, where English artists, magicians and showmen gave it a new life. Around 1823, the diorama – a portable theater that created the illusion of motion through the application of a light source behind a painted screen – showed up in Paris. Photography was invented in 1839, the same year the Sir David Brewster patented his 3D viewing device, the stereoscope. In the second half of the century, writers and dramatists as diverse as Charles Dickens and August Strindberg were championing magic lantern and photographic technology for their stagecraft. A Christmas Eve production of Dickens’ “The Haunted Man” at London’s Royal Polytechnic Institute in 1862 featured holographic figures reflected from below the stage interacting with flesh and blood actors. When, in 1895, Georges Méliès showed up for the first public screening of the films of the Lumière Brothers at the Grand Café in Paris, he saw his opportunity to update Robertson’s phantasmagoria using the illusionistic technologies of the past century. As Scorsese revived Méliès’ filmmaking through 3D, Méliès, through the motion picture camera, gave Robertson’s illusions a new lease on life for audiences who were by now accustomed to visual spectacles both realistic and wondrous.

Méliès’ films were fantasies, full of haunted castles and fairy kingdoms, underwater palaces and witches’ dens. He made versions of Faust, Bluebeard and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; his movies featured men who turn into bats or disappear in a cloud of smoke, variations on magic tricks improved by stop motion cinematography. The magic lantern limited Robertson to creating stories through still images in rapid juxtaposition. Thanks to the movie camera, Méliès could capture motion itself, yet the style of his illusions remained indebted to Robertson’s phantasmagorical metamorphoses.

In Hugo, the visual touchstone for Méliès’ pictures is the memorable image of the rocket going into the eye of the moon – a still from A Trip to the Moon, a picture he made in 1902. In this scene, Méliès gives the impression of the moon getting closer and closer – the way an object looks when we, in fact, are getting closer to it. The shot is from the perspective of the rocket, hurtling through space, and Méliès creates it through an inward zoom of the camera so that the moon gets bigger, bigger, bigger until the rocket hits smack into its eye, a final effect created through stop motion. It’s precisely the kind of visual trick the phantasmagoria, which included dissolving views and zooms in its limited repertoire, could achieve. I don’t think it’s an accident – it’s homage. A Trip to the Moon is the story of a league of astronomers who plan the first moon voyage, but Méliès’ version of science is a fairy tale – these wizardly professors conquer the man in the moon, after all. The movie is a parable about film itself, about the work of artists to discover unknown lands and explore new frontiers – dreamscapes, geographies of wildest imagination. Méliès tips his hat to an era in which artists were also scientists, sorcerers, showmen and explorers. In 1902, every trip to the movie theater was a trip to the moon.

There is no cynicism about technology in A Trip to the Moon, only a childlike sense of wonder, which may be why the First World War – which brutally exposed what mortal horrors humans were capable of with technology on their side – was so fatal to Méliès’ career. His film studio was repossessed by the war effort and turned into a hospital for wounded soldiers, and his film stock confiscated and melted down to make boot heels. In furious despair, Méliès burned hundreds of his films along with all his magnificent sets and costumes. That was in 1923, after the war: he was bankrupt both financially and spiritually. The space ship his fanciful astronomers had taken off in two decades earlier had been designed in the shape of a bullet, but perhaps it was not until the war years that Méliès learned for himself what Robertson, a veteran of one of history’s bloodiest revolutions, knew from the start: that the wild pursuit of freedom of imagination could also bring the deepest destruction.

****

Hugo is based on Brian Selznick’s children’s book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, but it is really a movie for adults, one that asks us to restore the belief in the magic of movies that comes so easily to kids – to accept filmmaking as an art of fantastical transformations, of ghostly returns and moon travel, of total surrender to narrative illusion. The fairy tale aspects of the film are part of what makes it so pleasurable, but like in a Méliès picture they are not meant to be taken exactly literally: it’s the suspension of disbelief, the willingness to enter a space in which our waking lives cross over with our dreams, that Scorsese is after. The 3D images recall us to the giddy innovation of artists and showmen like Robertson and Méliès and everyone who came in between – a time when visual technologies were endlessly advancing and audiences endlessly willing to be astonished.

What makes Hugo more than a fairy tale is its recognition that our most naïve responses to art can sometimes be our most sophisticated – that it is often our credulity and our sense of wonder that connects us to what is real. The Winter’s Tale, my favorite Shakespeare play, expresses this the best. It’s another romance, a story about an old tyrant king whose paranoid suspicions of his cherished wife’s infidelity leads to her death and the loss of their newborn daughter. The arc of the play is one of complete, even fantastical, redemption. Sixteen years pass: the daughter grows up a shepherd girl, and finds her way back to the court where she is reunited with the father she never knew she had. In the final scene the noblewoman Paulina, a trusted advisor to the king, takes him and his daughter behind a curtain to show them a sculpture of the dead queen, a likeness so extraordinary it fills the king with exquisite despair. And, in the most truly magical gesture of any work of drama I know, Paulina brings the statue to life. “It is required/ You do awake your faith,” she tells the king – and the audience – as the sculpture breathes and steps from the pedestal. Like Hugo, who makes the mechanical boy work again only to be rewarded by becoming whole himself, the king reaches out for an image of his wife and touches the warm skin of the woman he loved. Paulina operates a theater of benevolent subterfuge, where the naïve suspension of disbelief, the willingness to believe in enchantment, is itself the magic spell. It is required you do awake your faith.

The audience for The Winter’s Tale does not only bear witness to the spectacle of transformation but to the act of witnessing itself – for it is not only the queen who is transformed but the king who watches her metamorphosis with wonder. The statue scene may be the queen’s rebirth but it is the king’s redemption. It is always possible that the king is being tricked, that there never was any statue, just as audiences at 3D films who enjoy the sensation of immediacy, of being fully immersed within an illusion, are definitely being tricked. But the point in Hugo and of The Winter’s Tale is that it is the faith of those who bear witness that can turn a simple trick into a state of grace. And if movies are symbolic resurrections, it is always the audience being brought back from the dead.

Amanda Shubert is one of Full Stop’s founding editors. A PhD student in English at the University of Chicago, she also writes regularly about film and visual art for Critics at Large (www.criticsatlarge.ca).

This post may contain affiliate links.