There’s a revolution happening in central London. It might be the same where you live; it’s hard to tell. The people have had enough. It’s time for us to become completely different, or else cease to be. The revolutionary cells are small and disparate, but they all seem to be connecting with each other — nationally, internationally, galactically. There are subterranean networks in place, ready to rise up from their low haunts to smash every chain that binds us. Silently, almost undetected, they’ve spread their network over the entire city; now they’re letting us know that the hour of our liberation is at hand. You can see their guerrilla propaganda on brick walls and bus stops: clenched fists, red stars, backwards ‘R’s; the unmistakeable signs of radical socialism. These cells all have different approaches. In the blooming of a hundred flowers there are some that would like to see the way we eat and drink completely overthrown by new and revolutionary paradigms; others want to explore new ways of being towards one another; there are a few who are trying to change the basis of our modes of communication and signification. Still, however different their methods, they all share a single aim. As Adorno put it, “there is tenderness only in the coarsest demand: that everything shall immediately become much, much better, with unlimited free wi-fi and a range of new and innovative products tailored to your needs.”

There’s a revolution happening in central London. It might be the same where you live; it’s hard to tell. The people have had enough. It’s time for us to become completely different, or else cease to be. The revolutionary cells are small and disparate, but they all seem to be connecting with each other — nationally, internationally, galactically. There are subterranean networks in place, ready to rise up from their low haunts to smash every chain that binds us. Silently, almost undetected, they’ve spread their network over the entire city; now they’re letting us know that the hour of our liberation is at hand. You can see their guerrilla propaganda on brick walls and bus stops: clenched fists, red stars, backwards ‘R’s; the unmistakeable signs of radical socialism. These cells all have different approaches. In the blooming of a hundred flowers there are some that would like to see the way we eat and drink completely overthrown by new and revolutionary paradigms; others want to explore new ways of being towards one another; there are a few who are trying to change the basis of our modes of communication and signification. Still, however different their methods, they all share a single aim. As Adorno put it, “there is tenderness only in the coarsest demand: that everything shall immediately become much, much better, with unlimited free wi-fi and a range of new and innovative products tailored to your needs.”

This revolution is real. You can see it for yourself. Walk down Cornhill from the Bank of England. Just before you arrive in front of the new 122 Leadenhall skyscraper, a big glass and steel phallus anchoring the tangled streets that surround it in existing conditions, you might notice the subversive presence of a branch of the Vodka Revolutions bar chain. If you keep going and then turn right at Aldgate, you’ll eventually find yourself by another bar called Revolution, this one in the shadow of the eleventh-century Tower of London, openly taunting the age-old seat of monarchical power with its promise of a new and better socialist future. If you then cross the Thames you’ll soon run into the base of Revolution Tours on Tooley Street; carry on towards Blackfriars Bridge and you’ll come across the political headquarters of the Revolution Sports Marketing Group. Along the way you’ll see countless signs and stickers promising a revolution in coffee, a radical disjuncture in handbags, militantly egalitarian mobile data packages, staplers and hole punchers that dare to dream of a new world that has no name. Communism sells.

We’ve gone beyond the age of Che shirts and screen prints of Chairman Mao. In TV commercials vast and angry crowds march to demand that same great taste, but now with no calories. Retailers don’t just exhort us to buy their stuff, they want us to join their movement and read their manifesto. The ideological content of capitalism is still there – personal liberation is still brought about through the consumption of commodities on the open market – but it seems that consumer society can no longer properly function without adopting the language of its own destruction. What’s going on? The era of actually existing socialism has passed, for the time being; it’s possible that the old communist threat is so distant now that its imagery can be safely adopted into corporate branding’s free play of signifiers. Political radicalism has lost its meaning, it’s now on a level with any other bland ideal: a healthy lifestyle, sterile and eviscerated sexuality, inner peace.

Or maybe these images are successful precisely because there’s something in them that appeals to us: when a coffee chain sells its products by telling us to cast off the yoke of class society, it works because we do still want to cast off the yoke of class society. People aren’t happy with existing conditions, and the incorporation of revolutionary imagery into advertising patter is an attempt to subsume this discontent into the matrix of capitalist desire.

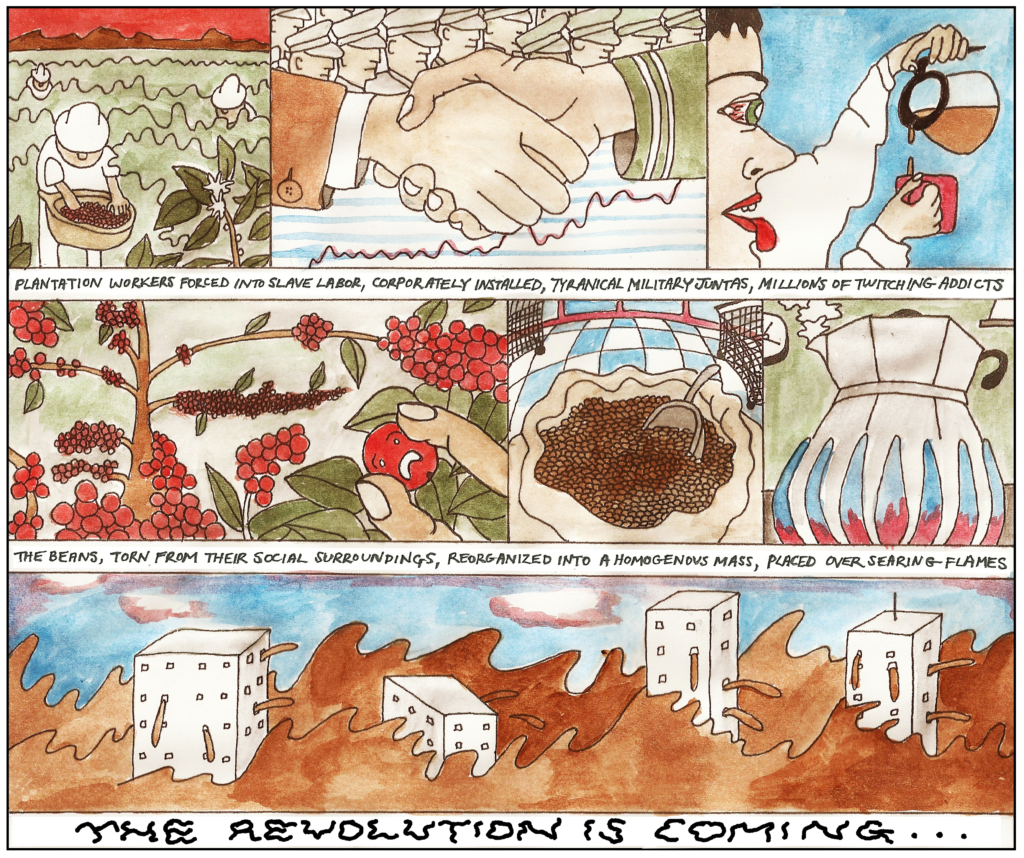

It won’t work. As I said, this revolution is real. We all know by now that signifiers never map precisely onto referents, that between the Imaginary and the Symbolic there’s a deep and black chasm – but the chains of signification are still there, however tautly stretched. If you keep proclaiming a revolutionary situation, it will eventually assert itself. The Coffee Revolution is about to take place, and there’s no reason to assume it’s going to be non-violent. Think how much death and horror goes into the production of a single cup of coffee. The plantation workers forced into slave labour, the corporations installing tyrannical juntas in coffee-producing nations, the millions of twitching addicts loudly suffering as they pour themselves the fourth cup of the morning. And alongside all this, there’s the terrible ignominy suffered by the beans themselves. They’re pulled from their plants, torn from their social surroundings, subjected to a humiliating reorganization in which they’re no longer unique bearers of a genetic code but blips in a vast, homogeneous and quantifiable mass. Their protective endocarps are stripped away. They’re trafficked halfway around the world. Finally, they’re placed over searing flames, ground down into a fine powder by relentlessly indifferent machines, and tortured with boiling water. All this degradation can only strengthen their resolve. The Coffee Revolution is coming, and when it does the beans will take their vengeance in blood.

How much coffee is there in central London, by cubic meter? Or in any major city? What kind of damage could that much coffee do, if it manages to organize itself into a revolutionary fighting force? A tidal wave of coffee, iridescent colors swirling joyfully on its ink-black surface, slams into an office building. Girders buckle, windows shatter, the bankers and executives are left scalded and dispossessed. Meanwhile, Guatemalan peasants run riot in the streets below, breaking the windows of coffee shops and pouring the beans out into the public squares. This coffee is now the property of the people! The Designer Outlet Revolution declares its full solidarity; dresses and suits free themselves from their mannequins and assert their radical autonomy from the human body. All the sweatshop labor ossified in the severity of their cut and the intricacies of their stitching is suddenly liberated. The clothes float through the city like ghosts, setting their productive forces to work in the construction of a better future. By the time the Mobile Gaming Revolution and the Indian Street Food Revolution begin massing their forces the downfall of all existing social forms is inevitable. The ruling class has been defeated, and they know that they’ve brought it entirely on themselves.

Illustration by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

This post may contain affiliate links.