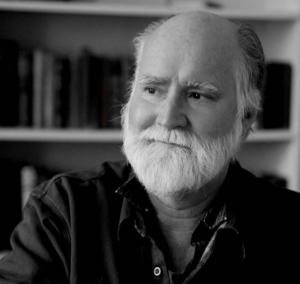

“I just had the most wonderful experience,” Nicholson Baker says as we sit down for breakfast at his hotel, “of walking around these blocks here in New York, playing ’80s oldies on my headphones. It’s a sunny day, and everybody’s going to work, and I’m out in search of toothpaste.” The comforts of music and enjoyable weather, the demands of toil and hygiene: ever since The Mezzanine established Baker’s fearlessness in the face of events so ordinary that they would send most writers running, it has been among the hallmarks of his style to strike at the mundane in the conviction that, hit just so, it will open up and yield something beautiful.

“I just had the most wonderful experience,” Nicholson Baker says as we sit down for breakfast at his hotel, “of walking around these blocks here in New York, playing ’80s oldies on my headphones. It’s a sunny day, and everybody’s going to work, and I’m out in search of toothpaste.” The comforts of music and enjoyable weather, the demands of toil and hygiene: ever since The Mezzanine established Baker’s fearlessness in the face of events so ordinary that they would send most writers running, it has been among the hallmarks of his style to strike at the mundane in the conviction that, hit just so, it will open up and yield something beautiful.

Another hallmark has been an increasing awareness of a different kind of strike, the kind that shatters the mundane and yields chaos and horror. In 2008, he published Human Smoke, a bracing, rhetorically unadorned selection of quotes and anecdotes about British war practices before and during World War II, which Colm Tòibìn called “an eloquent and passionate assault on the idea that the deliberate targeting of civilians can ever be justified.”

How contemporary Americans balance our roles as human beings to whom nothing much happens and citizens of a government that often makes terrible things happen is one of the major subjects of Baker’s new novel, Traveling Sprinkler, a sequel to 2009’s The Anthologist. Traveling Sprinkler revisits poet Paul Chowder as he worries about American policy, pines for and tries to win back his ex-girlfriend Roz, and starts to write songs. This might sound lugubrious, but the result is the opposite. A novel possessed of a sort of avant-garde friendliness, Traveling Sprinkler is casual and chatty, and reading it feels like taking a long car ride with a brilliant, warm, funny companion who is more interested in generously confiding doubts than in stingily defending positions. Or like having breakfast with him.

An edited version of our conversation appears below.

David Burr Gerrard: Is there such a thing as craft in fiction?

Nicholson Baker: Of course you can get better at writing if you do it a lot, but the moments when I feel I’ve got the craft down are usually the moments when I’m writing least well. There’s something useful about being humbled by the difficulty of what you’re doing, and by the sense that you’re trying to figure it out. It’s maybe better not to know what you’re doing, or at least that’s what I tell myself, because most of the time I really don’t feel that I’ve figured it out. When I was starting out, I’d check out books from the library on how to write, and they were useful to me in that I rebelled against some of the rules.

Are there any rules that you do live by?

“Tell the truth” is vague enough to be useful. “The best is the enemy of the good.” That’s a helpful one if things are going badly. Get to the end. “Finish” is a helpful one that I have trouble with. It’s very hard to finish. It’s much more fun to set something aside and research and learn things about some brand new territory. Research is a terrible temptation, at least for me.

You wrote a book called Checkpoint, a conversation between two friends, one of whom wants to assassinate President Bush. You’ve said since that you regret publishing it. There’s a conversation in this book where Paul’s friend Tim is trying to tempt Paul into going down to Washington to protest drone strikes, and Paul is saying no. I was wondering whether this was an attempt to rewrite Checkpoint.

Maybe indirectly. I’m interested in the character who is not part of the action. I’m not part of the action. I live in Maine, I read the news. I’m unhappy about the news, I’m happy about the news. But I don’t have any direct participation. Once in a while, I go to a peace protest. But that’s about as much as I do. So I’m a little bit more like Tim in the case of this book than like Paul, in that sense, but only in that sense. And I’m married. But it seems to me that that’s the really interesting problem about being a reasonably well-situated American citizen. There’s no direct threat, no physical harm, and if we hear something that sounds like a lawnmower, it’s probably a lawnmower, and not an unmanned aerial vehicle. And that’s a really powerful fact of our life. But we can still feel indignation or unhappiness about policy. So how far do you go? Do you write a book? Do you light a candle? Do you write an op-ed piece? Do you say: “Oh God, I’m powerless and it’s hopeless?” I wanted my character to have all of those feelings at one time or another, and to worry through that problem of how to be a citizen who means well but is also fumbling through life.

One of my favorite things about this book is that it involves unhappiness with drones, it involves unhappiness with middle age, but at the same time it’s very lighthearted. It feels like a joyous book.

I’m so happy to hear you say that. It was a joy to write in a sense because it was such a liberation to go back to a character I knew well, and to realize that this is closer to how I talk and think than how I write if I’m writing a magazine piece, where there’s a sort of received style that you play with, and sometimes you get too show-offy. I’m fascinated by diaries, and this is sort of like a diary. Not quite. Is it a diary, is it a podcast? Is it just a set of ruminations? Does it add up to a novel? That’s part of the confusion of it all.

Paul mentions that he reads Glenn Greenwald’s blog, but there’s really no point, it’s not going to change anything. I loved that, because I waste a lot of my writing time reading Glenn Greenwald’s blog.

I am so admiring and jealous of the fact that Greenwald can come up with new ways to say these things that are true and important and need to be said over and over. And he comes up with powerful arguments. And of course he broke the Snowden story, so he’s now become someone who has not just presented opinions, but who has really opened up new windows and doors and made things happen. But the character is thinking: what do well-formed, beautifully compressed opinions actually do when the people on the other side are not listening? Don’t you need people sitting down in the sidewalk? Don’t you need people getting arrested in front of the White House? In the few times that I’ve gone to protests, it’s always hit me that doing things or refusing to move has an expressiveness and directs the concentration in a way that a beautiful op-ed piece doesn’t. The powerlessness of words is what interests me, and what interests Paul. In the end, I’m writing a novel, so what am I saying? The powerless of words? I’m putting it all in a book. So I’m confused.

And of course your books are very deliberately reserved in terms of action.

[Laughs.] Beautifully put. Yeah. Look at this day. This was a big day for me. I got up, I read some articles on my iPhone, I bought toothpaste, I listened to some music as I walked back. I get to talk to a very interesting person. Then I’m going to get on a plane and go to a different city. There’s very little, but this is big, because I’m in New York. And I think my life is fairly representative. Books and movies are so skewed towards action. You get fired, and that’s the inciting incident, or your wife leaves you, your husband leaves you. You come into some money. You are suddenly mistaken for a CIA operative. Something happens that is completely out of the blue, and you’re expected to have wise, thoughtful reactions to it. But actually, you’ve just become a person who is sort of running and keeping up. I don’t believe that whole thing of: Get the character in a tree and then throw stones at him. I don’t buy it. It’s a very bad piece of advice.

Because you’re probably not yourself, you’re just somebody at whom stones are being thrown.

Right. I don’t know how I’d react, but I’d probably be like most people: ducking and swearing and falling out of the tree. What’s interesting about that?

So what standards do you have for inclusion versus exclusion?

You come to the either/or gate. Should I go there? Have I over-freighted this paragraph? Should I include yet another observation? Maybe I can live without that one. Does it have some sort of strangeness that is making some sort of entreaty? Is it saying: “You haven’t thought about me enough” or “People haven’t paid attention”?

The odd thing about the reaction to this book is that almost everybody is most interested in the fact that I included a YouTube URL in the book. Such a tiny thing, but in the moment I thought: okay, I’ll be really adventurous. I didn’t know it would be the thing people really paid attention to. Maybe it was a mistake. I think it was a bit of nostalgic postmodernism. In the way that people paint a photorealistic painting of a street sign. “Look at this! Look at this sequence of letters! Think about the fact that it takes you to a human voice singing in a Paris hotel room. Look at that, and be happy.” So, at that point, I was just sitting there, thinking: “Well, I really want people to listen to Stephen Fearing. I really would like that. If my book could do one thing, it would be that people would actually be guided to listen to Stephen Fearing.” And of course the worst possible way to tell them to go, I guess, is to give them a dead YouTube link, because they’re going to make a typo. The best way is to type “Paris hotel Fearing” or something. So I kind of blew it.

But it does have a strong presence on the page.

With no underline under it. As soon as you underline it, the brain blocks it out. It knows it’s a link, and you don’t even look at it. But when the letters are all there, like some sort of serrated battlement, with all these ups and downs of capitals, it’s fascinating. And why? It says: Watch, question mark. A question mark in the middle, as though it’s still thinking.

Do you ever think: “This is a Nicholson thought, not a Paul thought”?

That’s a good one. Yes, I have had that problem. Ever since The Mezzanine, where those were really my thoughts. After that, I thought I had done that, with my thoughts, and since then I’ve tried to liquefy, melt them a little more. Not use bulleted lists and footnotes and all the technical trappings of that first book. But I have to be honest about it: I think almost all of the thoughts in Traveling Sprinkler are my own thoughts.

But Paul regrets, quite movingly, being childless, which is not true of you.

That’s true, that that’s not true. But it is true of my asking myself: “what would I feel like if I had not met my own wife?” She’s so important to me, so much the source of everything that I have done right. Without that love in my life, I don’t think I would have written any of these books. I would have whined and pined and been miserable and thought I’d made a terrible mistake. And of course I wouldn’t have had two children. If I hadn’t met her, I don’t know what would have happened. I would be dead now. That’s what I think. I would probably be dead. What Paul is saying is my trying to think through what life would have been like if I hadn’t found her.

Is she involved in your writing process?

When I’m discouraged, she says nice things to me. She’ll say: “Oh, come on, you’ve finished them before; this is what you always say when things go badly, but things go better.”

Where she’s terribly important is that she’s a much, much better reader than I am. She’s a careful reader, but also an intolerant reader. When she doesn’t like something, she just says no, and puts a blue line through it. And she’s almost always right. Sometimes I don’t do what she suggests, but mostly I do. Once I get a draft finished, I show it to her, and she’s saved me from so many excesses.

I wonder what Henry James’ writing would have looked like if he had had a partner.

I wonder, too. He would get these stern letters from William James: “Your new manner is just . . . I didn’t get it!” So they were maybe a team, in a strange way. But I think Henry James needed . . . well, obviously he needed more love in his life. Poor guy. A real partner would have probably helped him a lot.

Paul also says that he can’t really read novels. He loves to read all sorts of other things, but he can’t really read novels. Do you find that that’s true of you?

I go through phases. I can’t read novels of the moment. I have to wait until they’re older. I do love diaries, letters. And I love doing research, so all that research is nonfiction. I go to archives and read a lot of stuff that’s not even published. It’s so much fun to just read somebody’s memo from 1943. But I’ve been rediscovering Graham Greene. Not really rediscovering, that sounds like I knew him. I’d read Our Man in Havana when I was twenty. That and The Human Factor. And I’ve been reading some of Nabokov’s short stories. “Perfection.” Beautiful story.

Graham Greene is on the opposite end of the action spectrum.

His characters do a lot of thinking and wandering around. They’re very sad. Greene himself is too sad for my taste, in long bursts. But I’m always drawn to sad writers. Sad, lonely writers. Then it’s just a balancing thing, it’s like making a cocktail. “Now it’s time for some Benchley!”

One thing that was very interesting to me: Paul talks about Archibald MacLeish’s role in forming the CIA, and says that poets should probably stay out of politics.

It was sort of a throwaway line when I said that the moral of the story is that poets should stay away from politics, although I think it may be true that somebody like MacLeish was led astray and corrupted slightly by his closeness to Roosevelt and his feeling that he could control information. It wasn’t good for him as a poet. Then again, he had already been destroyed as a poet because by 31 he had won two Pulitzer Prizes, but then he realized that the really knowing New York scene of Louise Bogan and Edmund Wilson and even Elizabeth Bishop really had no time for him. He was a very depressive kind of guy, and, as other people did, he used the war as a pick-me-up.

It’s depressing in a way that you have these people who are accomplished writers who are still very war-like. There was a thought that part of the problem with Bush was his lack of interest in literature, his lack of interest in language, but an interest in those things doesn’t seem to make that much of a difference.

That’s a very interesting point, and I think I learned it most devastatingly with Winston Churchill. You may think his prose is heavy and bombastic, but he’s brilliant, he’s verbally brilliant. His mind was filled with poetry. Semi-dirty dance hall tunes, but he was enormously gifted in forming sentences. And he was completely crazy and hyper-violent and so destructive.

It called into question my whole Anglophilia, my whole feeling of reverence I had for the 19th century. The Edinburgh Review and Blackwood’s. Reviewers like Sydney Smith. Great speechifiers. They were willing to be quiet in the midst of a British empire that was doing just unthinkably awful things, daily. Their sentences were never better, and the brutality coexisted with that. How can that be? Somehow that made that kind of beautiful Victorian sentence suspect for me, at least momentarily. And Churchill is the inheritor of that.

Does that have something to do with the somewhat more plainspoken style of your recent books?

I think it does, yes. Something broke in me around the time of Human Smoke.

Switching gears significantly, you mention this one line from a pop song: “Life’s like an hourglass glued to the table.” I’ve thought about that line many times over the years, but it’s never occurred to me to write about it, because it’s from a silly little teenybopper song. I was extremely impressed that you said no, this is worth writing about.

Thank you. I’m so grateful to some of those pop songs. I’m so happy that they exist. That’s the contribution that this country really makes — pop songs, television comedy. Of course there are some novels, though maybe our greatest novelist was a Russian émigré — Nabokov. But song lyrics cement themselves into your brain. They’re there because of the music, but the music wouldn’t exist without the lyrics. It’s a wild collaboration, beyond understanding.

This post may contain affiliate links.