1) Kimchi can fuck off and die in a fire.

2) Teaching creative writing, my largest fear is fantasy. Besides regular pre-teaching nightmares about rape and coercion, about being bound and stapled to the whiteboard, I dream the night before class about fantasy, not of worlds or dimensions or the kinds of characters who have corresponding powers, of maps, but of students, my students, telling me (do they know me?) that they’ll be writing it.

3) That they’ll be turning it in.

4) But this blog entry for Full Stop is going to be about a romance novel. It’s going to be like a review.

5) My fear of fantasy, or genre, leads friends to remind me, “Ursula LeGuin,” and ask, what is literary fiction anyway, a genre-less drift of paragraphish stuff?

6) Confession: Here he is finally tapping into some really good shit is what I thought of Don Quixote in its pastoral parts, which I only later learned were a mockery — were the transplantation and strange placing, the laughter of a genre.

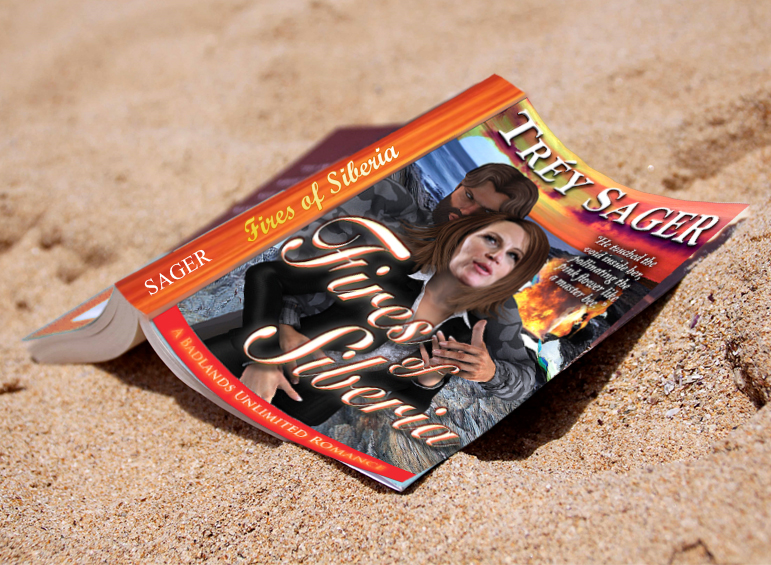

7) This semester I’m going to assign Trey Sager’s romance novel, Fires of Siberia, to my creative writing class at the University of Utah. This blog post for Full Stop is a letter to these students who I hope will find this, and also to Trey, my friend, and to the editors of Full Stop, two of whom I met in Santa Cruz this summer. They are so kind and interesting in a way that made me think “I do like America.” Fires of Siberia is a romance novel based on the life of Michelle Bachmann.

8) She wrapped her legs around him, melting him to the root with her pleasure tar, squeezing, tightening. Ripples uncoiled inside her, circles expanding beyond circles. One into two and two into none. Everything knowable.

Nothing worth knowing.

9) I didn’t know that Trey, my friend and an editor at Fence, a poet who has chapbooks out with Ugly Duckling Presse, was writing a romance novel to be released through Kindle and that I could buy on iTunes, about Michelle Bachmann, who I remember most for that willingness to foster a public health hysteria over Gardisil, which I had had administered to me, dutifully, before I was 25, in Montana. I remember feeling, 24 and ¾, ease, walking out of the student health center and looking at mountains and having gotten my Gardisil — one of the few things this center would cover. I didn’t understand, for a while, that Trey was serious.

10) Maybe I am throwing my students a bone, a genre bone for them but a joke bone. Except that Trey is serious.

11) “Yes. I thought that if I could fuck the Republican out of you, I could show you what was real. But the poem went deeper than that.”

As he spoke, Danielle’s focus drifted from his eyes to his mouth, mostly loitering there. He had pleasured her only hours ago. She’d tried to kill him afterward, and then he’d saved her from the Chechens. Now she was indebted to him. She wanted to hate him. He disgusted her. But the waves of his tongue still reverberating on her gladdened shores, his ebb, her flower, made it impossible.

His tongue was a secret trump.

It almost made her want to laugh.

12) The whole book is like that. “[H]is ebb, her flower,” is Trey finding the pockets, the little languid pools of language that are worth stretching into newer natures — words becoming a kind of sexual material, worth rearranging and interchanging, interfitting and finding again — “With him inside her, she became atmospheric, a sublime alphabet making indigenous meanings, sensual sutras that led to mutual enlightenment. . . He was everywhere. They were nowhere. His thighs roughly slapped against her backside in a carnal scheme of A + A. She hosted every lunge, then chased him and welcomed him in a virtuous cycle, and every time she took all of him, absolving him of that primal burden, granting him his erasure in a fissure full of truth.”

13) It’s not genre but cliché I actually fear. And it’s Trey’s use of the romance genre which actually explodes that awful kind of language, the kind that stays stale, says “ebb and flow” and does not find the flower there. Erasure in a fissure full of truth, Fissure a deep thing that is found in Erasure, a leaving thing, if paired with Full, a copulating equation of Truth, the alphabet dilating and spreading its fusion into parts.

14) Truthless mirth.

15) Outside, the sky spread out in a fearless epiphany, and the sun held it together like a thumbtack made of fire.

16) In a romance novel, the staleness preexists, is the stale vestibule, in which what happens always will. They will fuck.

17) And if you’re lucky, the language escapes — the way surgery manuals of the early 1800’s talk of the “heart escaping,” it escapes, can, inside the stale house swarming, and must. And Trey’s book is funny, satirically lush, is something my mom’s boyfriend, a writer of romance novels, enjoys as does BOMB. Kimchi can fuck off and die in a fire it begins, a car ride in South Korea before a plane over Siberia. You should read it on the train.

18) I met Trey in New York and we walked together through the flower district, a comedy of too many flowers on the sidewalk, talking about our novels — the novels we both were writing then and I am still. We stopped in front of a hat shop he likes and tried to guess, from the window display, each other’s Hats. He was right about mine and I was wrong.

This post may contain affiliate links.