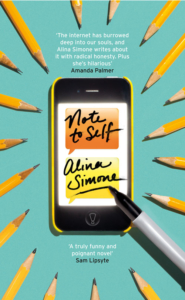

A quick look at today’s movies, TV shows, and books reveals that there’s a market for stories about the misadventures of young, unemployed Brooklynites struggling to find their place in the world. These kids pick up the kinds of odd jobs with touches of glamour that you can only find in New York City; they go to themed parties on roof decks; they have uncomfortable sex with questionable people. Alina Simone’s Note to Self, at first glance, fits right in — another cute story of an awkward/semi-hip broke girl searching for career and romantic satisfaction. Then you learn that the protagonist is 37, and she still hasn’t figured out her shit, and she relies on the Internet like a drug. And then it stops being cute.

Note to Self is a story of pathetic people who seek solace by reassuring themselves that there are people out there who are even lamer. Take our protagonist, Anna. Nearing middle age, unmarried, overweight, no close friends, living with a girl from Craigslist who’s ten years younger. She’s been recently fired from her job as a low-level employee at a law firm and is casting about to find her new life path.

In order to feel better about her own life, Anna kills her unemployed hours reading stories on disreputable websites about other people’s problems. This obsession with people who are more pathetic than she is has become a form of escapism that Anna can’t seem to escape from. She briefly fantasizes about writing a book about late bloomers — women who succeeded — but this idea doesn’t hold her attention; she turns back to reading about stories of failure.

As Anna’s real life remains unfulfilling, she seeks validation in the virtual world. She compulsively refreshes her inbox; she aches when she hasn’t checked Twitter all day. When she admits it, she calls it an addiction to the Internet.

Anna’s mysterious new acquaintance and occasional lover, Taj, understands the desire to seek validation in other people’s failure. Taj, whom Anna meets on Craigslist after answering a listing for an assistant on his filmmaking project (a job for which she is suspiciously accepted, despite being wildly unqualified), diagnoses the impulse behind Anna’s addiction to other people’s misfortune:

How does reading those long, glowing profiles in The New Yorker make you feel? Bad, right? Jealous. Scared. Insecure. Know what people really find comforting? Failure. Humiliation. Defeat. That’s what makes people feel better.

And Note to Self, with its abundance of failure, humiliation, and defeat, seems to be testing Taj’s theory. Whether it is correct — whether the book does succeed in being comforting or in making its readers happy — depends perhaps upon the reader’s tolerance for Schadenfreude. Given that Note to Self is a discussion of failure, Taj’s eventual betrayal of Anna, and the consequent nullification of all the progress that Anna seemed to have made throughout the book, is disappointing but ultimately unsurprising.

Regardless, Simone is gently reminding us that stories of failure are just a dose of painkillers for our loneliness. It’s easy to find false validation in other people’s messed-up lives — yes, things could always be worse — but this sense of satisfaction is short-lived, and once we click away from the story of the woman with eighteen children, what have we accomplished? And so the remorse about our own lives comes rushing back, needing to be endlessly staved off in a vicious cycle that leaves no room for the one thing that would fix us: real-world connections with people.

Note to Self is a book firmly grounded in place and time. It’s peppered throughout with painstakingly specific and up-to-date references — roller derby, unpaid internships, Hulu, McCarren Park, Gawker, Pom Wonderful — that place us squarely in Brooklyn in 2013. In another book, these of-the-moment references might feel irrelevant in a few years. However, Note to Self is more than just the story of a silly, aimless woman who spends too much time on her computer — it’s a nuanced exploration of what ails our society in this age of ever-expanding digital connectedness. In fact, it’s necessary for Note to Self to be about this exact moment in time, because the ill that Simone explores is nothing if not contemporary: the way, these days, we can be surrounded by virtual friends in social media, but still feel utterly isolated and alone.

This post may contain affiliate links.