There is a quote I like that shows up occasionally in my Facebook feed: “Never argue with stupid people, they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.” It is usually accompanied by a veiled insult from the poster and an image of a stern and stately Mark Twain, long the go-to guy for apocryphal maxims. This particular quote seems to be derived from Proverbs: “Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest thou also be like unto him” (26:4). As with many of Twain’s own lessons, however, this is immediately followed by a reversal: “Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own conceit” (26:5).

There is a quote I like that shows up occasionally in my Facebook feed: “Never argue with stupid people, they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.” It is usually accompanied by a veiled insult from the poster and an image of a stern and stately Mark Twain, long the go-to guy for apocryphal maxims. This particular quote seems to be derived from Proverbs: “Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest thou also be like unto him” (26:4). As with many of Twain’s own lessons, however, this is immediately followed by a reversal: “Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own conceit” (26:5).

Regardless of the quote’s origins, its sentiment is echoed in Twain’s “The Privilege of the Grave,” a short piece, written in 1905, that appears in Who is Mark Twain?, a posthumous collection of the satirist’s unfinished and unpublished works. “As an active privilege,” Twain says, “[free speech] ranks with the privilege of committing murder: we may exercise it if we are willing to take the consequences.” The main difference between the two? “Murder is sometimes punished, free speech always.” As a result, Twain suggests writing one’s true thoughts down and uttering them only from the grave. Fittingly, Twain specified that his autobiography was not to be published until 100 years after his death. (This request was honored, and the first volume of the book was published in 2010.)

I thought of these quotes over the last couple of days as a certain news story was passed around among Facebook friends. The story cites a new report by the fine fellows at the Cato Institute, and it alleges that in 35 states, people who receive welfare benefits make more money than those who work minimum-wage jobs. Some may see this as evidence that minimum wages are too low, but the report and the conservative news outlets that featured it instead criticize liberals for devaluing work and sentencing generations of poor Americans to lives of welfare dependency. For my friends, however, the lesson was much simpler: we would all be rich if it weren’t for poor people.

As its typical welfare family, the report presents a single mother and her two children, both under the age of five. This decision does not require a rationale, apparently, despite the fact that only 23% of single mothers have children under the age of six (with the largest percentage of those having only one). The choice does, however, allow the report’s authors to continually allude to the stereotypical “welfare queen” while they add benefit after benefit to the poor, greedy woman’s income.

She receives SNAP, WIC, TANF, Medicaid, Section 8, utility assistance, and more, each benefit added speciously, with reasoning like: “While not all low-income households receive utilities assistance, participation levels for households with income comparable to our profile family averaged almost 50 percent, sufficient for inclusion in the hypothetical benefits package.” And again: “While not all eligible low-income households receive WIC benefits, approximately 61 percent of eligible families participate in the program nationwide, which justifies including WIC in the hypothetical benefits package.”

Each time a benefit is added, our “typical” family becomes even more atypical, and as the authors perform statistical gymnastics rivaling those of a gambling addict, 23% becomes 11% becomes 2% becomes 1%. Meanwhile, a statistical study devolves into a fairy tale about a single mother with two children who never age, temporary assistance that never ends, and a free home with free electricity, which she uses to cook her free food.

The report ignores the fact that many people who work full-time, minimum-wage jobs qualify for some of these programs, too, as well as the fact that most able-bodied people who receive nutrition assistance, excluding children and the elderly, have jobs. Nevertheless, the conclusion is damning: “The current welfare system provides such a high level of benefits that it acts as a disincentive for work. . . . states should consider ways to shrink the gap between the value of welfare and work by reducing current benefit levels and tightening eligibility requirements.” Ironically, the Cato Institute also thinks that we should incentivize work by abolishing the minimum wage.

These are just a few of the points I typed and deleted below my friends’ Facebook posts, trying to not sound pedantic while others piled on above. The conversations soon spread to “Obamacars,” “Obamaphones,” and other entitlements funded directly from the paychecks of hardworking, Facebooking Americans. I found myself needing to point out that Obamacars are not real, and that discounted phones, which are not paid for with tax dollars, have been around for over a decade (previously as landlines) and actually help people secure jobs from employers who, for some reason, like to be able to contact their potential employees. But I refrained. As Twain says: “Sometimes my feelings are so hot that I have to take to the pen and pour them out on paper to keep them from setting me afire inside; then all that ink and labor are wasted, because I can’t print the result.”

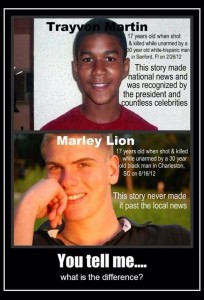

Anyone who has ever argued with people like this, or has witnessed some poor soul try, knows the futility of the endeavor. For every factoid discredited, the person has two more at his disposal, and he will casually toss them aside, one by one, until you understand that he has nothing invested in them. This if the conversation even makes it that far. When a commenter recently disagreed with our mutual friend posting an image comparing Trayvon Martin with Marley Lion, he was quickly rebuffed to the effect of, “You may have a point, but don’t ever call me out on MY Facebook wall again!”

Anyone who has ever argued with people like this, or has witnessed some poor soul try, knows the futility of the endeavor. For every factoid discredited, the person has two more at his disposal, and he will casually toss them aside, one by one, until you understand that he has nothing invested in them. This if the conversation even makes it that far. When a commenter recently disagreed with our mutual friend posting an image comparing Trayvon Martin with Marley Lion, he was quickly rebuffed to the effect of, “You may have a point, but don’t ever call me out on MY Facebook wall again!”

This inhibition may seem to run counter to the notion that Facebook has created a generation of unfiltered oversharers, highlighted by stories of young people posting incriminating pictures online. Whether social media has actually midwifed these monsters or has simply given them another outlet, I can’t say. (I can say that I recently sat next to a woman on the bus as she described the toe procedure she was about to undergo, and I wish she had been limited to 140 characters.) But the two behaviors are not antithetical.

A certain degree of safety is required to experiment with new personas and politics, a process of identity creation to which Sherry Turkle, author of Alone Together, attributes oversharing. We post things on Facebook that we wouldn’t say in person, Turkle says, because online, we do not face the immediate admonishment that can be conveyed in another person’s smirk or roll of the eyes or abrupt change of subject. Only the people who agree with us will take the time to comment, we assume; the others will simply scroll on to the next items in their feeds. It is natural, then, that the person who violates this contract must “take the consequences.”

I am always wary of blaming technology for human weakness, and indeed, Twain assures us that these behaviors are not novel ones. “None of us likes to be hated,” he says, “none of us likes to be shunned. A natural result of these conditions is, that we consciously or unconsciously pay more attention to tuning our opinions to our neighbor’s pitch and preserving his approval than we do to examining the opinions searchingly and seeing to it that they are right and sound.” Still, I am regularly disappointed to see a friend or colleague whom I have known for years call Trayvon Martin a deserving thug or attribute a bogus second amendment quote to a Founding Father.

Perhaps my friends have been harboring thoughts like these for as long as I have known them, reserving comment for company that does not include me. Or perhaps, despite a healthy ignorance of politics, a friend may decide, for one reason or another, that he wants to be political today, that after eight hours at the job he hates, he wants to console himself with the self-righteous thought that, at least he’s not a leech. Even if I consider this resentment misplaced, I know that it is best to let him have it. Tomorrow he will go back to talking about what he really cares about: his wife; his kids; his team; his car. And I will go back to scrolling.

Perhaps my friends have been harboring thoughts like these for as long as I have known them, reserving comment for company that does not include me. Or perhaps, despite a healthy ignorance of politics, a friend may decide, for one reason or another, that he wants to be political today, that after eight hours at the job he hates, he wants to console himself with the self-righteous thought that, at least he’s not a leech. Even if I consider this resentment misplaced, I know that it is best to let him have it. Tomorrow he will go back to talking about what he really cares about: his wife; his kids; his team; his car. And I will go back to scrolling.

Eric Jett is a writer, designer, and teacher from Charleston, WV. He is a founding editor of Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.