It’s not long after she marries the flighty and seductive Miguel, as they are hitchhiking back to Mexico from Kansas City, pregnant with her first child, that Claudia begins to hear voices. If we are to take her at her word, it’s Miguel’s fault; his drawing her away from the strict but comfortable home of her childhood, flirting with other women, going off mysteriously for long stretches of time, all of it leads to her breakdown. She feels her mind starting to slip, finds herself panicking for unknown reasons, ceases to sleep, begins talking back to those voices, screaming at them.

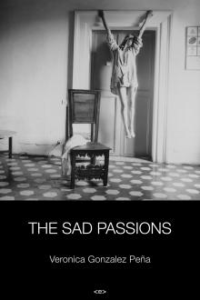

It’s at this point that Miguel takes her to a hospital where she is treated with electroconvulsive therapy, which leaves her drooling, shocked, and temporarily pacified. At this key moment of Veronica Gonzalez Peña’s The Sad Passions, the reader encounters the themes of force and psychiatric power that are so common in literature about madness, which often presents the medical profession in a critical light, as part of a larger process of rationality straitjacketing creativity, civilization suppressing the primitive — one might look to Septimus Smith’s suicide at the end of Mrs. Dalloway for an example. She describes the procedure: “They tied me up liquid and held me down solid and shoved something cold and hard into my mouth and then they gave me those shocks in my head.” The scene, with its barely suppressed resonances of sexual violence, the physical restraint, the mouthpiece shoved into her mouth, the husband who “watched while they did it,” would fit nicely as an example in Heroines, Kate Zambreno’s recent, innovative account of how transgressive women have been systematically repressed by psychological discourses and practices throughout our modern and contemporary (literary) history.

However, what makes The Sad Passions so fascinating as an example of fiction that deals with mental illness is that Claudia’s confrontation with a disciplinary psychiatry occurs only in this one brief encounter towards the beginning of the novel. Instead of limiting itself to uncovering the insidiousness of seemingly peaceful medicine and the violence of psychiatric labels, The Sad Passions records its own slippery diagnosis; a novel of effects, it measures Claudia’s undiagnosed or undiagnosable condition in the ways it becomes etched into the lives of her four daughters.

The Sad Passions consists of a series of alternating dramatic monologues spoken to an unseen listener. Claudia, her sister, and each of her four daughters — cautious Rocio, analytical Julia, truculent Marta, and precocious Sandra — each in their turn recount their childhoods. Following along this tortuous trail of reminiscence, the reader is granted access to a vast emotional and physical geography. While Claudia attempts to absolve herself of her failed motherhood, her sister refuting her claims at every turn, the four daughters attempt to make sense of lives formed in the shadow of a mother’s illness. Their reminiscences take them from the desert of Coahuila to the streets of Mexico City, from the clogged highways of LA to the quiet beaches of Long Island’s North Fork. These are stories told in small moments, moments of love, pain, longing, jealousy, fear, and sometimes beauty: Sandra standing transfixed at the sight of a tornado in the desert, Rocio enviously waving as she watches Julia driven into the distance, Marta bitterly recalling the night her sister abandoned her at a party, Julia exploring the traces Mexico City’s mythic past through the murals of Diego Rivera. Each speaker presents her perspective in turn, each chapter taking on one of their voices, accounts sometimes overlapping, often contradicting.

Always hovering at the edges of these remembered moments are a pair of questions. Each speaker looks backwards and forward asking both, “What caused our familial dysfunctions? What prevented us from being a happy family?” and “How can I move forward, break away, start anew?”

It is in investigating that first question that the novel’s polyphony really pays off, allowing Gonzalez Peña to layer competing claims to truth and configurations of blame: do we blame Claudia for her cruelty? Her father for his strictness? Miguel for his ego? Do we blame mental illness? Do we find fault with each daughter? Do we look to Mexico’s colonial history, which, placed in acute juxtaposition with this history of a family, echoes back a common past of myth and violence? One might treat each of these options with a sensible eye to discovering which is right, untangling the honest accounts from the lies. This is what Claudia’s sister Sophia proposes to the reader at the end of her single chapter, “You be the judge. Look at the life. What do you think?” But it seems more likely that in this novel, it is as Claudia describes: “There is no center, the one way of telling merely a cover for the others, a layering, like sand or ash or soot, a piling up of truths.”

It’s not that The Sad Passions, in leaving psychiatry behind early in the novel, neglects to account for the causes of Claudia’s suffering. Each daughter, in her turn, attends to their mother’s acts of wildness and of indifference, small and large: flirting shamelessly with their friends or abandoning them for days in a house in the desert. From Claudia’s perspective, it is the men in her life, the power they have always held over her, which forces her astray. Her chapters serve as a series of botched confessions. Rather than accepting responsibility for these actions, she mines her past for proof of an outside cause. In her efforts to absolve herself of these failures to live up to the role of the good mother, she points to her flighty husband Miguel, doing so with a degree of repetition which cannot but induce a measure of skepticism: “It wasn’t me. It was never my fault. It was M, I tell you. He was the badness. Until him I had never felt myself slipping. Until him everything had been just fine.” Implicitly, the indictment stretches further into her past, to her father whose strictness and callousness, Claudia’s stories suggest, drove her to greater and greater emotional instability.

This notion that Claudia’s sections raise, that we acknowledge the ways women like her are stifled and caused to suffer, accused of failure and transgression for both their wildness and their callousness by a culture which paradoxically privileges attitudes of both callousness and wildness in men like Miguel and Claudia’s father, is a legitimate and important one. But Claudia is also drawn as an unreliable narrator; her suspiciously incessant finger pointing, her sister’s counter-claims, her mother’s defense, with its hints of the medical and the religious — “She is not right. She does not know what she says, does not know what she’s done. Forgive her” — and her daughters’ own negative accounts all suggest that the causes of fractured families and psychic suffering are far too complex to be done away with through a simple accusation.

In puzzling over the question of cause the novel abets a degree of relativism in the reader, contrasting accounts not cancelling each other out, but generating a particularly rich depiction of a woman’s psychic and emotional struggles, born of biology and systemic violence and personal failings. But what is so singular about the novel is the way Gonzalez Peña renders the transmission of this violence and the reverberations of this suffering through family history.

Beyond their desire to make sense of the past through storytelling, each daughter’s narrative represents an attempt to claim an autonomous future. In the wake of their tumultuous childhoods, Rocio, Julia, Marta, and Sandra each find themselves struggling with the myth of coming of age, attempting to slough off an encumbering past, the burden of nurture and of nature. “I decided to pull it all off, like a heavy coat, the weight of my family and what it had done to me,” Sandra asserts early on in the novel, and each of her sisters in turn makes a similar claim, finding solace in friends, in lovers, in travel, in writing. But neither their attempts to remake themselves within the narrative, nor the ultimate act of self-writing that they perform in telling us their story, allows them to sever all ties. Instead, they are forced to confront again and again the traces of their mother in themselves, to admit to the force that their familial ties, both contextual and genetic, continue to exert over their futures — “I’m terrified,” Rocio confides to her husband, “What if I turn into her.”

A novel that teeters between a past and a future both marked by their relation to a mother’s disease could easily become a plodding exercise in morbidity. But if this is a novel of illness or pain, it is also a novel of family, and the makeshift systems of intimacy that can spring up to fill those spaces of rupture. The family ostensibly examined by the novel is a failed thing, constituted by absences: the physical absences of the father, who swoops in only periodically in order to take them all off on road trips and to strange desert towns when the gambling has been good; the emotional absences of the mother, sometimes a husk of a person, barely there, although other times all too present; and finally, perhaps most importantly to the overall movement of the narrative, the mysterious absence of Julia, the daughter sent away to live with an uncle in New York by Claudia in a quintessentially unmaternal act which precipitates envy, resentment, fear, and confusion in her other children.

But in the place of a happy home we find a compendium of delicate configurations of family that are constantly exploding the nuclear form. These families, founded by acts of love, caring and kindness, performed between sisters, cousins, friends, strangers, between generations, between species, are not distinct from the novel’s sad passions, but born out of them, through them. In one particularly harrowing scene, Julia wakes in the night to find her mother staring fearfully at the door, mumbling paranoiacally, her fingers bloody, nails bitten to the stubs. “I felt very lost,” Julia admits. Her subsequent response, shouting at her mother, shoving her out of the apartment, locking her outside, finally opening the door, letting her in, leading her to bed, tucking her in, kissing her forehead, is contradictory, in turns cruel and caring, violent and maternal.

Reading The Sad Passions is a conundrum, an exercise in both empathy and ambivalence. The indelible marks of a mother, a family, an illness fail to speak for themselves. Much like the characters who narrate the novel, as readers we are left with our inclination to judge, to make sense, to assign blame. But, as Gonzalez Peña shows, mental illness is a site where our scripts break down, where our determinations of cause and effect, our theories of ethical behavior, reach their limit. And so she bids us to bear witness to this family trauma, to these moments of affection, leads us back, again and again, until we are left confused, exhausted, somewhat battered, but for all that, intimately connected to these characters.

This post may contain affiliate links.