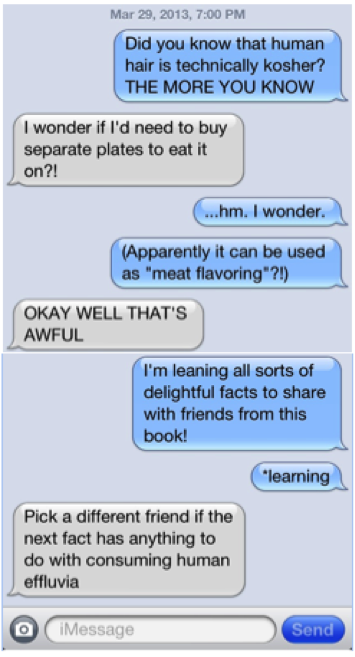

It seems, perhaps, that Mary Roach’s books are not for everyone. As “America’s funniest science writer,” as the Washington Post calls her, she is fascinated by the disturbing and the downright weird — often in contexts where many people would find little to laugh about. Her first book, after all, was Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers. Her new book, Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, does indeed deal with what my friend so eloquently described as “human effluvia”: Gulp begins with the nose and ends in the rectum, passing through, in more or less chronological order, the various stages of the human digestive system. Roach explores the history of scientific investigations into the curious, strange, and confusing idiosyncrasies of the digestive system, from the importance of smell in tasting to the pressing question of whether or not Elvis died from constipation.

Mary Roach comes across as chatty, endearing, and incredibly smart, prone to puns and hilarious asides. She is a writer you could imagine having lunch with — although, based on her research interests, probably in a private place, if only to save your fellow diners’ appetites. Not so incidentally, restaurants are a recurring setting for interviews in Roach’s books. The first chapter of Gulp begins in one, an Oakland bar called Beer Revolution, where Roach meets with Sue Langstaff, a sensory analyst — that is, a person who analyzes taste and, evidently most importantly, odor in food. Langstaff is the first of many interviewees and historical figures, whose titles run from the relatively prosaic (wildlife biologist) to the interesting (sensory analyst) to the downright bizarre (“the voice of the Beano hotline,” for example, or the man with the “open fistulated passage” in his stomach that allowed researchers unparalleled access to the workings of his insides). Roach, as she writes in her introduction, is less interested in writing about generally taboo subjects, such as cadavers or feces, than in “these men and women, the scientists who tackle the questions no one else thinks — or has the courage — to ask.” The history of science, in Roach’s work, is the history of human curiosity and obsession, and Roach has these in spades.

“The human digestive tract is like the Amtrak line from Seattle to Los Angeles,” notes Roach in an early footnote: “transit time is about thirty hours, and the scenery on the last leg is pretty monotonous.” Not monotonous enough, perhaps, and luckily for us. The last seven chapters are about the latter part of the digestive process, the “last leg” and its delightful peculiarities, from Chapter 13, “Dead Man’s Bloat and Other Diverting Tales from the History of Flatulence Research,” to the penultimate Chapter 16, “I’m All Stopped Up: Elvis Presley’s Megacolon, and Other Ruminations on Death by Constipation.” It’s not all stories about poop, however: Chapter 12 contains an invaluably informative footnote about the origin of the synonyms inflammable and flammable. Apparently,

Flammable is a safety-conscious version of inflammable. In the 1920s, the National Fire Protection Association urged the change out of concern that people were interpreting the prefix in to mean “not”—as it does in insane. Though surely those same people must have wondered why it was necessary to warn of the presence of gas that will not burst into flame.

“I don’t want you to say, “This is gross,”” Roach writes at the close of the introduction to Gulp: “I want you to say, “I thought this would be gross, but it’s really interesting.” Okay, and maybe a little gross.” As an ars poetica, this statement is a wonderfully apt description of Roach’s method. Roach’s writing is unreservedly ingenuous, for all her insistence that she’s left the really gross stuff out, and you get the impression that while she understands that some may find her topics disgusting, that response has honestly never occurred to her. It’s an infectious enthusiasm, to say the least. If Gulp fails in any way, it’s in Roach’s overwhelming interest in stories rather than analysis: Chapter 2, for instance, although ostensibly titled “Why We Eat What We Eat and Despise the Rest,” is more about the relationships other cultures have with foods generally seen as inedible in America than about “race- and status-based disgusts.” This absence is negligible, however, since Gulp’s focus is very much on these stories rather than on cultural analysis — Roach’s third book, Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex, for instance, worked in much the same way.

I want to amend my opening statement. In the time it’s taken me to write this review, the friend of that initial conversation has borrowed Roach’s earlier book Stiff from me: the immediate response of disgust, it seems, giving way to curiosity, in a shift that would surely do Mary Roach proud.

This post may contain affiliate links.