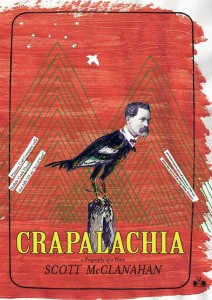

For a book that is so acutely aware of the inevitability of death, Crapalachia is still somehow infused with a wonderful sense of hope. Again and again, Scott McClanahan returns to the topic of mortality, both his and our own: reminiscing over beloved relatives who have passed away, warning of the swiftness of our days and the ticking of the clock, quietly contemplating the reasoning behind it all (if any). For a purported “biography of a place,” the book certainly seems to have a more philosophical than historical bent. But McClanahan’s is a joyful philosophy, communicated via his own distinctive melange of poetic storytelling and direct address, and never less than an enthralling read.

Most of the book consists of stories from McClanahan’s teenage years living in West Virginia. The first part of the book describes life with his grandmother and uncle, while the second part focuses on his time spent sharing an apartment with his best friend during their waning high school years. McClanahan has a prodigious gift for description — his depictions of family and friends are so lovingly observed and evocative that they feel like conjurations of their actual spirits. His grandmother, Ruby, is an outsize influence on his young life, full of personal conviction and strange compulsions, such as taking photographs of the recently deceased in their caskets:

“What?” Ruby said after I told her what they said.

I repeated it: “They said they couldn’t develop pictures of dead bodies anymore. It’s their policy.”

Ruby just looked so confused: “You mean they won’t develop pictures of people you know anymore. Well how are you going to remember them? How’s an old woman gonna remember all of ‘em?”

I said: “It’s probably because of privacy laws and stuff. I’m sure there are not too many people bringing in pictures of dead bodies anymore.”

So Grandma Ruby kept working on her quilt with this funny look on her face.

Her son, McClanahan’s uncle Nathan, is a middle-aged man who has suffered from cerebral palsy his whole life and has never left the confines of his wheelchair or his mother’s home. He also seems to have inherited his mother’s fascination with death, though this is manifested in his case through constant suicidal thoughts, so sick is he of being trapped in a body that won’t obey his commands for half of a century. Nevertheless, he has a fantastically bawdy sense of humor, can beat McClanahan handily at checkers (his favorite game), and never takes even the smallest social interactions with others for granted. This particular family situation could be — and in a lesser author’s hands, would be — easily parlayed into the blatantly sentimental, which is what makes McClanahan’s accomplishment all the more impressive. These are living, breathing people, full of sound and (at times) fury that don’t necessarily have to signify anything. McClanahan asserts this forcefully on behalf of Ruby at one point:

She knew how to make biscuits from scratch and slaughter a hawg if she had to. And she knew how to do things that are all forgotten now – things that people from Ohio buy because it says homemade on the tag. I looked at the quilt she was working on. The quilt wasn’t a fucking symbol of anything. It was something she made to keep her children warm. Remember that. Fuck symbols.

McClanahan is also a keen observer of specific moments in time. In many of Crapalachia’s scenes, much of his descriptive power is derived from actively remembering people’s physical surroundings: furniture, clothing, knickknacks. It’s as if the objects in these people’s personal orbits are imbued with memories of their owners and McClanahan is mentally picking up each one individually, turning them over, attempting to thereby remember their owners’ essences: “It was my uncle Nathan’s checkerboard, all beat up and taped together in the middle. I sat and ran my fingers over the checkerboard and I thought about ghosts.” Repetition also functions as an aid to McClanahan’s memory here, and some of the most potent instances of this are found in his initial descriptions of life with his end-of-high-school roommate, Bill. Bill has extreme OCD, and when McClanahan first moves in with him, he quickly realizes the extent of Bill’s compulsions:

The next morning I woke up to the lyric:

I close my eyes, only for a moment and the moment’s gone. All we are is dust in the wind.

I came home the next day, I close my eyes, only for a moment and the moment’s gone.

I went to bed each night. All we are is dust in the wind.

The repetition of those “Dust In The Wind” lyrics would feel a little too on the nose thematically in most situations — here, it’s made poignant by virtue of its role in Bill’s rituals, and renders McClanahan’s own realization of its importance to himself all the more powerful. This significance hits McClanahan fully some time later in the book, when Bill is absent: “I didn’t know what to do without him . . . Then I went back to the closet and got out the CD. I put it in the player and pushed play. Then I started singing along, ‘I close my eyes, only for a moment and the moment’s gone. All we are is dust in the wind.’ I listened to the whole song and then I did it again.” Memory transforms the trite sentiment of the lyrics into something much more plaintive.

The book is so full of this unmistakable feel of lived-in memory that it’s a bit of a disappointment to read the appendix and discover that some characters were blends of two different people in McClanahan’s past, while others went by different names and/or familial relations, and certain events didn’t actually happen at all. It’s not disappointing to learn about these facts in and of themselves — McClanahan’s voice is so thoroughly enjoyable throughout the book that any excuse to have the chance to read more of his writing is welcome. But it feels largely unnecessary, not least because one of the points McClanahan makes in the appendix is the irrelevance — indeed, the incoherence — of any purported fact vs. fiction divide in the pursuit of truth: “I just realized that I never look at a painting and ask, ‘Is this painting fictional or non-fictional?’ It’s just a painting.”

Having expressed this so eloquently, the rest of the appendix comes across as extraneous, maybe even counter-productive to that idea of truth’s capacity to be conveyed through both fact and fiction. I don’t know if you’re legally obliged to provide all the facts if you’re going to put the word “biography” on the cover of your book these days (the James Frey clause?), but we shouldn’t have to know if McClanahan is telling us the unvarnished historical facts of his youth, and there is no need for him to come clean on Oprah — Crapalachia speaks for itself and effectively asserts its right to do so. I do know that even if I hadn’t read the afterword, I would have gleaned the same pleasure from such assured storytelling, and appreciated just as much its elegiac call to savor life now, today. As Joan Didion would have it, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live,” and if that’s the case, then Crapalachia is written proof of McClanahan’s intent to inhabit every moment to its fullest. We are lucky to get to share in the fruits of his labor. Crap-e diem.

This post may contain affiliate links.