“This is not your fight — it’s not your country, it’s not your Prime Minister,” my uncle writes to me in a Facebook message from his home in Moscow, where he got stuck for almost 22 years after bearing witness to the fall of the Soviet Union. “Stay away from this stuff.”

“This is not your fight — it’s not your country, it’s not your Prime Minister,” my uncle writes to me in a Facebook message from his home in Moscow, where he got stuck for almost 22 years after bearing witness to the fall of the Soviet Union. “Stay away from this stuff.”

* * *

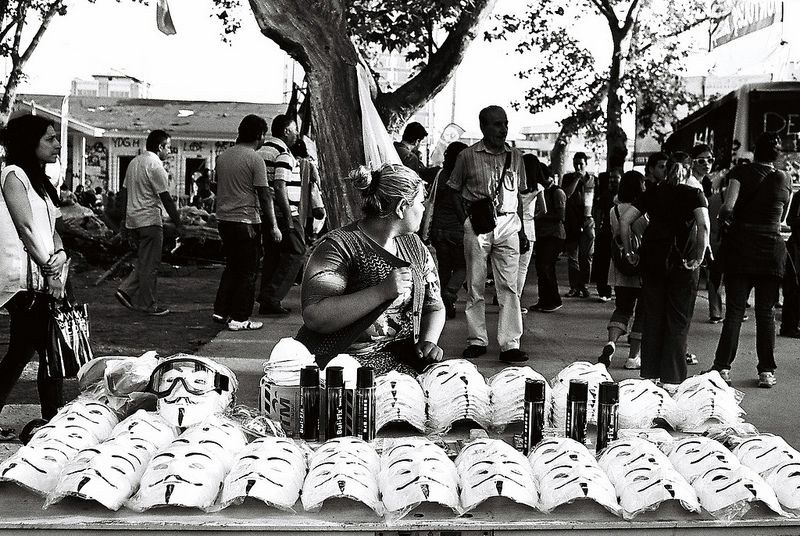

As I walk up İstiklal (“Independence”) Avenue towards Taksim Square and Gezi Park, I notice that the density of vendors who are capitalizing on the mass appeal of what some are calling revolution is getting thicker and thicker by the step. Where, just a few days prior, there were hoards of people running from the countless teargas canisters being launched from every direction, there are now people selling street-food, scarves and flags decorated with the face of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (the founding father of the Turkish Republic), Guy Fawkes masks, goggles. They also sell the simple painters’ mask I’ve been wearing to mitigate the effects of the teargas that inevitably makes its way into my body as I participate in these massive demonstrations, alongside people who are resisting an oppressive autocracy and demanding that their(/our) voices be heard in the decision-making processes that dictate the rapid transformation of their(/our) city.  A vendor slicing up giant watermelons yells “Buyurun, çapulcu!” (‘here you are, marauder!’/’come and get it, ya bum!’).[1] The price of what some of my friends and I have jokingly termed “riot-köfte ekmek” or “revolution-köfte ekmek” (something like a Turkish meatball sub) is rumored to have risen to 10 Turkish Lira (between 5 and 6 USD) over the past couple of days. The revolution-köfte I purchased in Gezi Park, together with a plastic container of the Erdoğan-endorsed yogurt drink Ayran on the side, set me back 8 TL a few days ago. I don’t know what’s going to happen to Gezi Park, to Istanbul, to Turkey, and I don’t know where I’ll be when whatever happens does, but I know that it would be a shame to have to live with the fact that I was in Istanbul for the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and I missed out on revolution-köfte.

A vendor slicing up giant watermelons yells “Buyurun, çapulcu!” (‘here you are, marauder!’/’come and get it, ya bum!’).[1] The price of what some of my friends and I have jokingly termed “riot-köfte ekmek” or “revolution-köfte ekmek” (something like a Turkish meatball sub) is rumored to have risen to 10 Turkish Lira (between 5 and 6 USD) over the past couple of days. The revolution-köfte I purchased in Gezi Park, together with a plastic container of the Erdoğan-endorsed yogurt drink Ayran on the side, set me back 8 TL a few days ago. I don’t know what’s going to happen to Gezi Park, to Istanbul, to Turkey, and I don’t know where I’ll be when whatever happens does, but I know that it would be a shame to have to live with the fact that I was in Istanbul for the Gezi Park protests in 2013 and I missed out on revolution-köfte.

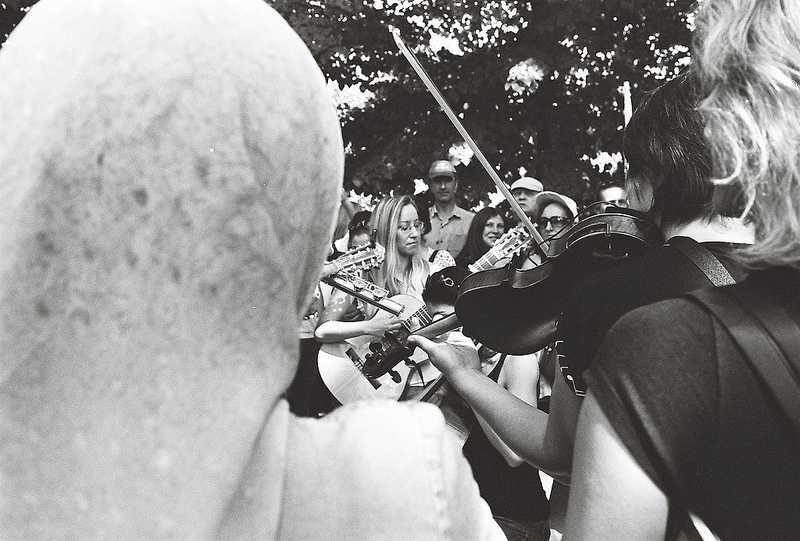

I’m sitting on the grass in a crowded, shady spot in Gezi Park where people are socializing, reading, taking naps, and sometimes joining in as groups of people chanting, making music, and dancing pass by. People are coming up to me with trash bags and asking me if I have anything to throw away and others are offering me homemade börek (a Turkish filled pastry made from very thin, flaky dough, that’s just as ubiquitous as it is delicious) from Tupperware containers and some kandil simidi (savory cookies that are usually only consumed on religious holidays) that some pastry shops have donated in large quantities to feed the anarchic society that’s blossomed here since the police retreated on Saturday. It’s hard to write here, but there’s nowhere else I’d rather be. I find that I’ve become extremely attached to the park, and sometimes when I’m not here I start feeling a mixture of guilt, fomo and longing. But now I’m sitting by myself (kind of), waiting to meet with a friend and listening to an impromptu marching band break it down a couple paces away. I watch as a mother passes with a baby strapped to her chest. The contraption that’s holding the baby to its mother’s torso is adorned with a red felt cape that has “#direngeziparki” embossed in white on its back.

* * *

I’ve seen only brief flashes of Ece for the past couple of days. She’s been staying in and around the park, taking night shifts to protect the barricades that protesters have constructed out of cobblestones, bricks, scrap metal, car parts, portable police fences, gutted public buses and whatever else they can find. She’s also been offering injured protesters first aid on their way back from facing off with the police at the front lines. I wake up to find Ece sleeping upstairs next to a young man I’ve never seen before, and I quietly retreat to the kitchen to make some breakfast. They eventually wake up along with my flat-mates, and we all congregate in the kitchen and have a good laugh about the “Call of Duty Taksim” graffiti that was spray-painted on the sidewalk and then broadcasted on Facebook. Ece and Erdem have quite a collection of battle wounds between the two of them, yet somehow, with the late morning light and cool breeze streaming in through our kitchen window in Tarlabaşı (a notoriously rough neighborhood that, like many spaces in Beyoğlu and all over Istanbul, is also slated for demolition and “renewal”), we can find a way to laugh about the surreal nature of the altercations that continue to occur, night after night, between the protesters and police in the areas surrounding Taksim Square.

Ece live-translates as Erdem, a Turk who grew up in Bulgaria and doesn’t speak any English, animatedly tells us about how he had to learn how to operate a digger, which is apparently much more complicated than operating a car, when he was defending a barricade a few nights prior. He got the hang of it quickly enough to successfully intercept some of the tear gas canisters with the machine’s giant claw, and block the currents of pressurized water coming from the vehicles equipped with water cannons that the police were using against the unrelenting protesters on the ground. We joke about the rising price of köfte ekmek in the park, and about whether the cranky aunties in hand-embroidered floral-print headscarves tending the grills are actually undercover cops. We sit together and watch a message from a participant in the Egyptian uprising, imploring protesters in Turkey not to make the same mistakes that protesters in Egypt did, and then Democracy Now!’s coverage of the events that have taken place in our city. We were all surprised and excited to learn that Erdem is featured, shown picking up a teargas canister and throwing it back towards the police. Later that day, as I sit with Ece and her mother in the park, typing up a transcript of the records she’s hurriedly scrawled on pieces of scrap paper and kept with her for the duration of her involvement with the protests, she tells me about when, a few nights prior, she had collapsed from the effects of teargas in the outdoor seating area of the fancy cafe on the grounds of the Dolmabahçe Palace (an opulent residence that housed six Ottoman Sultans and one Father Türk). As she was trying to run towards the neighboring mosque that had been repurposed that evening as a hospital, two policemen approached her, swinging their batons menacingly as one of them yelled, “I’ll shove this baton up your cunt.” A young man interrupts us to ask if we can post on Twitter that there’s a dog in need of veterinary attention near the steps leading up from the square to the park.

I was walking back to the park from another episode of trying not to piss on my shoes behind the Gezi Bosphorous Hotel when I noticed a large crowd of people gathering near a set of speakers and holding up their smartphones. I approached the scene, and found that there were people dancing Argentinian tango with crinkled sheets of paper bearing #occupygezi, #direnrize, #direnankara, and other popular hashtags and phrases taped to their backs.

* * *

As the park has gotten more crowded, it’s become increasingly difficult to find people who you’re supposed to be meeting, so Danya and I arrange to meet at the “Gezi Speaks” wish tree, a participatory art project involving people tying the wishes they’ve written on small pieces of paper to a sculpture of a tree made out of found objects and growing out of a pit of rubble.[2] We make our way to the park for a stroll, and get wrapped up in another conversation about how the international media coverage glosses over some of the nuances and key components of this movement by affiliating it with the Arab Spring uprisings on the one hand, and the Occupy movement on the other. The reductive cliché that defines Istanbul in the popular imaginary is that it’s a place caught between East and West, that it somehow marks the point where the East stops and the West begins and vice-versa, as if East and West ever stop and begin, but it feels salient in this moment.

It makes all too much sense that the events that have transpired in this place where Danya and I both find ourselves more-or-less incidentally living would garner such comparisons. We start to enumerate the ways in which what’s happening here in Turkey lies both in between and completely outside of Arab Spring and Occupy. “This is more occupy than Occupy ever was,” Danya says. Soon enough our voices are drowned out by the now-familiar sounds of traditional Kurdish music, which we follow towards a large assembly of people gathered around a group of queer boys shaking their asses to the beat of the bass drum and the lively melody played by a wind instrument. One of them is waving a rainbow flag, another is sporting a red feather boa, another is holding up a feminist tract. Everyone in the remarkably diverse crowd is dancing along, taking videos and pictures with their smartphones and cheering for the dancers. Eventually, an angry-looking, hyper-masculine young man in a Galatasaray football jersey makes his way through the crowd and confronts the queer with the loosest hips, and, I think, the cutest smile, and it looks for a second like things are going to get ugly. Luckily, a very well put together middle-aged woman dressed in a long coat and a headscarf turns around and swats the homophobic footballer away. He obediently retreats. Soon the dancers clasp pinkies and assemble into a circle, inviting the onlookers to join in a Halay.

* * *

Irmak is a new friend, a friend of a friend. She’s been glued to her computer screen, like all of us, following the protests from her home on the Asian Side, but today is the first day she’s been able to make it to Taksim. When we meet her on the square, it’s clear that she’s completely stunned by the lively atmosphere, and even more so when we make our way into AKM (Atatürk Kültür Merkezi), a now-derelict shell of a building that used to function as a multi-purpose cultural center and opera house. Her mother worked there back when it was a place where people could work, and she spent a lot of time there as a child. Now, the government has designs to build another opera house, and possibly a mosque, in its place after completing the demolition. Mehmet, another friend, remarks that it looks and feels like some of the industrial ruins he’s seen on his trips to Berlin, where he’s thinking of moving in order to put off and shorten his mandatory military service. Through the forest-green construction mesh that’s covering some of the openings in the precarious structure, we can see that a bus has exploded into flames on the square, and people are running up with fire extinguishers, trying to put out the blaze as quickly as possible.

We ascend the makeshift stairs, and I stop to take pictures, waiting for the rest of the people who’ve stopped by with their smartphones to move out of the frame so that I can properly capture the building in all of its ghostly, ruinous glory. My camera runs out of film and I load a new roll of black and white that I’ve been avoiding using since my friend in Ukraine with a surplus supply insisted I take it off his hands. I’m out of color. Eventually we make it to the roof, where, from the south-facing side of the building, you can see an incredible panorama of Istanbul in its infinity. The Bosphorous looks nice from most angles, but this is really something special. From the north side, the view is just as interesting, but in a very different way. We look down at the crowds of people filling the square and the park, and I try to explain what Where’s Waldo is to Irmak, who’s never heard of it before. A banner bearing the slogan “Boyun Eğme,” instructing its public literally not to bend their necks — not to give up or give in — hangs from the front facade of AKM. It was one of the few banners hanging when the three of us climbed into the building. Soon after, the facade was completely covered. Now, this is what AKM looks like. Someone fell and got hurt in the building, and some Gezi Park residents organized a security team to prevent people from entering and possibly endangering their safety.

We ascend the makeshift stairs, and I stop to take pictures, waiting for the rest of the people who’ve stopped by with their smartphones to move out of the frame so that I can properly capture the building in all of its ghostly, ruinous glory. My camera runs out of film and I load a new roll of black and white that I’ve been avoiding using since my friend in Ukraine with a surplus supply insisted I take it off his hands. I’m out of color. Eventually we make it to the roof, where, from the south-facing side of the building, you can see an incredible panorama of Istanbul in its infinity. The Bosphorous looks nice from most angles, but this is really something special. From the north side, the view is just as interesting, but in a very different way. We look down at the crowds of people filling the square and the park, and I try to explain what Where’s Waldo is to Irmak, who’s never heard of it before. A banner bearing the slogan “Boyun Eğme,” instructing its public literally not to bend their necks — not to give up or give in — hangs from the front facade of AKM. It was one of the few banners hanging when the three of us climbed into the building. Soon after, the facade was completely covered. Now, this is what AKM looks like. Someone fell and got hurt in the building, and some Gezi Park residents organized a security team to prevent people from entering and possibly endangering their safety.

* * *

The Devrim Müzesi (Revolution Museum) in the park smells like piss, and as Osman and I pass by he inquires if perhaps it’s a bit too early for a museum. Someone’s lying down next to me on the grass, reading Tolstoy in translation and yelling for a cigarette.

* * *

These impressions were collected roughly between May 31 and June 10. Since writing this piece, the violence in Istanbul has escalated dramatically. There have been reports of a shocking number of detentions, injuries, and even deaths in both Istanbul and Ankara. Each story, each video, each image is more disturbing than the next. The park, what the park was, is gone. To keep updated on what’s happening in Turkey, you can follow Al Jazeera’s live blog. Mashallah News was also keeping a live blog when there weren’t many other news and media sources covering these events in English. The page is still up, and on it they have an excellent list of links to English-language resources, as well as articles, websites, images and videos that provide good background information and analysis. Turkish Awakening is a great blog by a British-Turkish journalist who lives very close to Taksim Square. Here’s a link to the official website of the Taksim Solidarity Platform. Nar Photos provides fantastic photographic coverage of the protests in Istanbul. You should watch this movie, this one too (for laughs). Vice made a short documentary called Istanbul Rising that’s worth watching. Here are a couple short videos produced by participants in the Istanbul protests.

Hannah Klein is an erratic maker from Cincinnati, Ohio, USA with a flair for walking in cities. Hannah kind of lives in Istanbul, Turkey and kind of has a website.

This post may contain affiliate links.