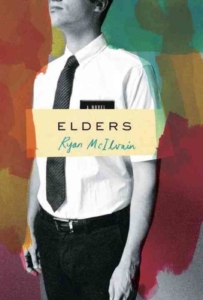

Ryan McIlvain’s debut work of fiction, Elders, is a “Mormon novel” in that it centers on two twenty-year-old Mormon missionaries in Brazil, a country that is home to a Mormon population in the millions. Set just before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the novel takes up themes of religious custom, dogma, and lore, but maintains an understated secular baseline. In interviews, McIlvain doesn’t hide his Mormon upbringing. But he also refuses to frame his twenty-something decision to stray as an indictment of the Church of Latter Day Saints (LDS), or as a wholesale rejection of faith. He maintains a silent and undecided stance toward his religion — it’s this uncertainty that seems to lie at the heart of the story, creating an unresolved tension throughout and resulting in some of the novel’s best qualities. The broad acceptance he affords believers and non-believers is likely the result of his refusal to take an official stand. In Elders, he gives both — the Mormon faithful, and those who stray from their faith — a much-needed human face. On second glance, then, this is less a “Mormon” novel and more a human story about the challenges of faith, personal growth, and the complexity of interpersonal connection in a multicultural setting.

As former Mormons like McIlvain know well, severance with the Church is no easy task. Tight-knit LDS communities in the United States take membership retention as seriously as missionary work, with persistent door-to-door outreach supported by a well-oiled bureaucracy. Abroad, proselytizing missions rest on this same grassroots work ethic. In the novel’s Brazilian favela setting, these efforts are met with skittish tolerance. Locals come to their doors “in the unwind after work, or with the looseness of alcohol, or out of sheer recreational curiosity,” if at all.

The novel’s third person narrative closely inhabits both protagonists, Elder McLeod and Elder Passos, as they near the end of their mission term in which they’ve been paired together. McLeod is a Connecticut native whose rebelliousness and anti-establishment brooding fester under a broken religious identity. Passos, the once-Catholic Brazilian who converted after his mother’s death, is McLeod’s foil in devoutness, at times contrivedly so. Passos ranks more highly than Mcleod, but Mcleod’s distinctly American bluster makes Passos recoil. The senior elder identifies more with the sentiments of anti-American, anti-war drive-by hecklers than with his companion. Having been force-fed its imagery, Passos also resents the English translation of the New Testament, whose white-washing of religious iconography tests his acceptance of Mormon gospel.

Neither Elder is immune to the corrosive cynicism at the heart of their dysfunction. “Perhaps the ranks of believers and doubters had already been determined, split along an eternal binary,” writes McIlvain. “The heart swells with belief, like a child inside you — or it doesn’t. The ground is fertile, or it isn’t.” McIlvain’s insider perspective as a former Mormon is the true fulcrum of this seesaw between belief and doubt, and he strategically obscures its tilt. Which way it leans by the end is less crucial to his point than that it wavers at all in the first place, or if it ever stops. In this context, the weight of ambivalence is greater than any final oath.

The narrator pays close attention to the boys’ private thoughts and revels in their doubt (and its deep bodily grip), making up for their occasionally stilted dialogue. McIlvain’s best descriptive writing emerges when his characters are physically suffering. In his initial encounter with the missionaries who converted him, Passos describes a “feeling of nervousness like nausea, the feeling that only got stronger as the lesson progressed, drawing all clarity of thought and speech into a merciless orbit around it. The stress of caring.” McIlvain’s way with words on the subject of queasiness is another means by which he rounds out this otherwise opaque character. Relatedly, such frank bodily descriptions humanize the boys and subtly reinforce the point that man’s body, despite its best intentions, can never truly achieve holiness in spite of itself. It will always be sick, get old, and die. So no matter how earnestly the boys pursue spiritual purity, their bodies will always get in the way. This may be a further expression of the struggle between belief (personified in man’s brain) and doubt (personified in man’s body) that lies at the crux of their experience.

McLeod also processes his existential confusion physically, boldly ignoring the advice featured in the “Guide to Self-Control” pamphlet, which warns Mormon boys of the dangers of masturbating. Passos scorns Mcleod’s willingness to indulge and goes so far as to light Mcleod’s pornographic contraband on fire. The scene would be cartoonish if not for the narrator’s slowed-down attention to the incident’s details, such as “a shapely leg curling up and turning charcoal black.” The boys’ experience is most vivid during these observational play-by-plays.

While McIlvain’s attention to detail allows him to express the ambivalence and doubt that accompany his characters’ religious superegos, it is also through this focus on the everyday that he outlines how community can spring up in a world of spiritual difference. The popular Brazilian soft drink, Guaraná, which they stop to guzzle along their daily house-call route, is the prop in another of these protracted, meditative moments that punctuate the monotony of their days. The same way coworkers with nothing in common but mutual resentment can genuinely enjoy each other’s company over a bag of chips in the cafeteria every day. McIlvain uses this “water-cooler conversation” trope to evoke Passos and McLeod’s potential for finding common ground. It’s a quiet, quotidien ritual that reinforces, despite boundaries of language and social mores, the value of a shared human experience, repeated daily

This post may contain affiliate links.