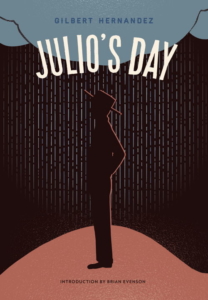

The term “coming out” has a curious etymology. George Chauncey, in his history Gay New York, traced it to the drag parodies of debutante balls popular in Harlem in the early part of the 20th century. The gay-rights movement came to define the term more firmly, marking it as the point in which one breaks from a life of dishonesty inside the closet to a life of self-acceptance outside of it. Several groups in the past few years have appropriated the term for their own ideological needs. Play around with Google and you will discover the stories of Republicans who come out in Berkeley and atheists who come out in Alabama. I don’t find these groups’ appropriations insulting but their stories do not include that one most touching and universal element of the gay coming-out experience. The moment a gay man or woman comes out is a moment of exhilaration but also a moment of sadness, marked by mourning for the lost time spent inside the closet. Straight people read coming-out stories because we all, straight and gay, mourn the missed opportunities, the unconsummated love and the misguided shame of our past. In his new graphic novel Julio’s Day, the straight Gilbert Hernandez uses the closet as an encapsulation of the many ways human beings both waste and make use of our short tenure on this earth.

The term “coming out” has a curious etymology. George Chauncey, in his history Gay New York, traced it to the drag parodies of debutante balls popular in Harlem in the early part of the 20th century. The gay-rights movement came to define the term more firmly, marking it as the point in which one breaks from a life of dishonesty inside the closet to a life of self-acceptance outside of it. Several groups in the past few years have appropriated the term for their own ideological needs. Play around with Google and you will discover the stories of Republicans who come out in Berkeley and atheists who come out in Alabama. I don’t find these groups’ appropriations insulting but their stories do not include that one most touching and universal element of the gay coming-out experience. The moment a gay man or woman comes out is a moment of exhilaration but also a moment of sadness, marked by mourning for the lost time spent inside the closet. Straight people read coming-out stories because we all, straight and gay, mourn the missed opportunities, the unconsummated love and the misguided shame of our past. In his new graphic novel Julio’s Day, the straight Gilbert Hernandez uses the closet as an encapsulation of the many ways human beings both waste and make use of our short tenure on this earth.

Julio’s Day tells the story of a man whose lifespan spans the entire 20th century from 1900 to 2000, as if all one hundred years of his existence took place in one day. The book opens on the tiny black space of the baby Julio’s open mouth, pulling back panel by panel to reveal his cradling in his mother’s arms and then finally a studied symmetrical composition in which mother and child are flanked by Julio’s grandmother, father, uncle and two siblings. They are straight-backed, simply-drawn people, a humble Mexican family from an isolated town somewhere in the American Southwest. The tremors of history will reach this family and their neighbors, while internal discord and terrible disease will kill them off one by one. This Julio, quiet, gentle, and to the end of the novel a virgin, partner-less and childless, will stand as the great weight at the family’s center.

Everyone has compared the work of Gilbert Hernandez and his brother Jaime in their series Love and Rockets (in which Julio’s Day first appeared in serial form), to prominent examples of “Magic Realism” (this particular book is a retelling of One Hundred Years of Solitude). There is a key difference. Garcia-Marquez’s Buendías are extraordinary men and women, all at least a square-inch larger than life. Julio’s kinfolk and neighbors, save for one degenerate uncle, are decent men and women, children of a giant and beautiful if indifferent earth, drawn by Hernandez in engulfing whites and blacks. Some of them are heroes of their own tall tales; one neighbor serves as a nurse in almost every conflict the United States fights, even in her dotage, paying her own way to serve in the first Gulf War. But, by and large, their world obeys our own rules of science and they are destroyed by the forces of history and nature that they can neither control nor comprehend.

Only a bastard God would inflict such a series plagues upon one family, plagues Hernandez describes with brutal depictions of either diseased bodies or aging bodies. In one episode, Julio’s father sets off on a long journey, the reason for which is never explained, on which he suffers a blueworm infection which deforms his thin frame, transforming him into a tumescent grotesque. Julio’s sister falls in love with the town’s handsome young epileptic, who returns from duty in World War I with most of his limbs destroyed, and his mind rotted. The ghost of the handsome youth still visits her in dreams as her own body follows a more conventional course towards old age and death. In his youth, Julio falls in love with Tommy, a poor white boy. Tommy gets married and has a large family, but the two remain dear friends until death separates them. As they age from Adonises to relics, Hernandez always positions their bodies tantalizingly close to one another, their romance forever unconsummated. In death, longing, or disease, each member of Julio’s family suffers their own closet-like solitude through these one hundred years.

Time spent inside the closet, the book seems to argue, is not time lost. Each minute spent in solitude is a minute spent in silent contemplation of our own existence. “Races condemned to one hundred years of solitude do not get a second chance on this earth.” That line would have no place here. Hernandez’s book suggests that Julio’s family, despite all the time nature and history rob them of, do not need another chance to make anything right. They emerge as simple lines from the mud and disappear back into the mud, leaving behind nothing but the simple crosses in a cemetery. There is no need to argue for or against the value of their painful sojourns on this earth.

This post may contain affiliate links.