Back in December, a story called “Why I Will Never Sleep With an On the Road Fanatic” appeared on Nerve. In about 1200 words, author Kate Hakala recounts the many ways in which the modern beatnik archetype, as set out by Jack Kerouac in On the Road, is not worth her time.

Back in December, a story called “Why I Will Never Sleep With an On the Road Fanatic” appeared on Nerve. In about 1200 words, author Kate Hakala recounts the many ways in which the modern beatnik archetype, as set out by Jack Kerouac in On the Road, is not worth her time.

“I understand that it’s romantic — this notion of endless wanderlust, searching high and low for the beauty and wonder in new life experience,” Hakala writes. “[But] Sal, Dean, and the gang don’t speak with people, but rather, past them. They do not understand the nature of experience, only the idea of experience. There’s a lack of connection, a neglect of any deeper side to humanity than what you can get on a road trip.”

Having gone to a school that regularly ends up on some list or other of top ten hipster colleges, I recognized the type and thought the article was very funny. Other people seemed to enjoy it, too — more than a thousand readers liked the story through Facebook, and it sparked dozens of comments discussing the pros and cons of On the Road. It all got me thinking about why it is that the previously unthinkable has happened — why it is that the eternally cool Kerouac is, well, no longer cool.

When Viking Press first published On the Road in 1957, New York Times critic Gilbert Millstein immediately praised it as a “major novel”:

It is possible that it will be condescended to by, or make uneasy, the neo-academicians and the “official” avant-garde critics and that it will be dealt with superficially elsewhere as merely “absorbing” or “intriguing” or “picaresque” or any of a dozen convenient banalities, not excluding “off beat.” But the fact is that On the Road is the most beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by the generation Kerouac himself named years ago as “beat,” and whose principal avatar he is.

Everything Millstein wrote is still as true today as it was 56 years ago. Perhaps the problem nowadays is that while Millstein was reviewing a book fresh off the presses and about a different take on life than people had seen before, we in 2013 have since become too saturated with it. On the Road has sold nearly 3.5 million copies in the United States, and sells between 110,000 to 130,000 every year. Maybe too many people have read it, too many copies have been dog-eared and passed around; maybe too many people have extolled the virtues of the open road in books, blogs, and Instagram; maybe we’ve just heard that burn, burn, burn line too many times.

Whatever the reason, On the Road no longer holds the allure it once did. Its wild, reckless, and unpredictable characters are no longer revolutionary; the buttoned-up culture it was rebelling against didn’t survive the 1960s; its relationship to consumption seems naïve and immature in a time when our relationship to our consumerism is more complex than ever. Hakala describes the modern-day version of Kerouac as “a twenty-eight-year-old with Peter Pan syndrome hitchhiking to Burning Man and texting me on his mom’s family plan.” Burned, indeed.

* * * *

On the Road is one chapter of an opus that Kerouac called the “Duluoz Legend,” a series of barely fictional novels that make up the bulk of his work. “The whole thing forms one enormous comedy,” Kerouac describes, “seen through the eyes of poor Ti Jean (me), other wise known as Jack Duluoz, the world of raging action and folly and also of gentle sweetness seen through the keyhole of his eye.” Kerouac’s style of “spontaneous fiction” reads like a frenzied personal journal, a quality heightened by the fact that Kerouac wrote extremely quickly and usually without any revision (he finished On the Road in three weeks after being on the road for seven years). “It’s not the words that count,” he wrote, “but the rush of what is said.”He admits that his work is essentially autobiographical, with only the names of his personae changed from those of his real-life friends.

The difficulty of separating Jack Kerouac the novelist from Jack Kerouac the brand is no new idea. In a 2004 story in The New York Times, Walter Kim wrote that, “Beginning with the publication of On the Road, [Kerouac’s] name has been used to sell so many attitudes and promote so many fashions that the artist behind the image has been obscured.… Even people who may have never read him want a piece of Kerouac, it seems.… Kerouac is no longer just an artist. He’s a lifestyle god.”

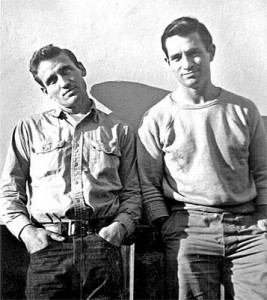

Kerouac’s iconism has remained so deeply rooted in the collective conscious of America largely thanks to the media. “Still young in years and handsome as any movie star,” describes Ann Douglas in an introduction to The Dharma Bums, “blessed with a voice that was in itself a musical instrument, a lightning-swift mind, and an uncanny instinct for absurdist comic timing and impromptu gloom-and-glee drama, Kerouac became an overnight sensation, the first literary figure of the full-fledged media age, interviewed on TV talk shows and reading his work to jazz accompaniment.”

On the Road struck a chord with post-war America, setting the stage for the beatniks, hippies, and rebels without a cause of the 1960s and 1970s. And for the past half-century since its publication, Viking has successfully repackaged the novel for each subsequent generation, providing the reading masses with original scrolls and 50th anniversary editions. Everyone has his or her own version of Kerouac, describes Kim: “For certain left-wing baby boomers, Kerouac is a political figure first — the great Eisenhower-era proto-hippie. For New Agers, he’s a spiritual pioneer who helped make America safe for Eastern religion. For college kids with powerful car stereos, he’s the original road-trip party hound.”

For me, Kerouac fell into the latter category until very recently. I’d read On the Road four times from ages 14 to 24, but it wasn’t until just a few weeks ago that I felt the urge to pick up another Kerouac novel. Having now read two additional chapters in the Duluoz Legend, it’s clear how much more there was to Kerouac than On the Road. In the larger span of things, that novel was just a fraction of the opus he assembled — it just happened to become incredibly famous before any of the others. But it takes reading some of them to get a better sense of Kerouac, including his reaction to the unexpected fame that On the Road brought him.

The Dharma Bums, which was written as a quasi-sequel to On the Road, was published in 1958. As the character Ray Smith, Kerouac delves into Buddhism under the guidance of his friend and fellow poet Gary Snyder, whose character is named Japhy Ryder. Kerouac, already an alcoholic, attempted to abstain from alcohol, sex, drugs — all the temptations of his fast-wheeling city life — by escaping into nature and onto the road, hitchhiking and hopping on trains across the country and up the California coast.

Even though he had some sense of divine inspiration in remaking his life, Kerouac/Smith was never able to wholly stick to the new life he’d laid out for himself: “I really thought myself some kind of crazy saint,” he wrote. “And it was based on telling myself ‘Ray, don’t run after liquor and excitement of women and talk, stay in your shack and enjoy natural relationship of things as they are’ but it was hard to live up to this with all kinds of pretty broads coming up the hill every weekend and even on weeknights.”

But whenever Kerouac/Smith tries to explain his thoughts on Buddhism, he felt ostracized. “They never listened,” he wrote, “they always wanted me to listen to them, they knew, I didn’t know anything, I was just a dumb young kid and impractical fool who didn’t understand the serious significance of this very important, very real world.”

This me-against-the-world feeling continued into Big Sur, published in 1962. In that novel, Kerouac is Jack Duluoz, a writer wholly overwhelmed by the success of “‘Road’ the book that ‘made me famous.” In that period, he sunk even deeper into alcoholism to cope with the constant attention — “Me drunk practically all the time to put on a jovial cap to keep up with all this but finally realizing I was surrounded and outnumbered and had to get away to solitude again or die.” He escapes from San Francisco up to his friend’s cabin in Big Sur, but eventually his old life seeps back into the tranquil solitude he’s found in the woods.

His friends come up to spend the weekend with him, bringing with them an idealistic young beatnik who, naturally, idolizes Kerouac/Duluoz. When the two are left alone together, Kerouac, drunk, just wants to sleep, but he must instead “make the best of it and not disappoint [the beatnik kid’s] believing heart”:

Because after all, the poor kid actually believes that there’s something noble and idealistic and kind about all this beat stuff, and I’m supposed to be the King of the Beatniks according to the newspapers, so but at the same time I’m sick and tired of all the endless enthusiasms of new young kids trying to know me and pour out all their lives into me so that I’ll jump up and down and say yes that’s right, which I cant do anymore—My reason for coming to Big Sur for the summer being precisely to get away from that sort of thing—Like those pathetic five highschool kids who all came to my door in Long Island one night wearing jackets that said ‘Dharma Bums’ on them, all expecting me to be 25 years old according to a mistake on a book jacket and here I am old enough to be their father—But no, hep swinging young jazzy Ron wants to dig everything, go to the beach, run and romp and sing, talk, write tunes, write stories, climb mountains, go hiking, see everything, do everything with everybody—But having one last quart of port with me I agree to follow him to the beach.

Not only does Kerouac seem disdainful of his celebrity, but he’s also disdainful of the very beatnik movement that he so widely represents.

The Dharma Bums and Big Sur are just two novels out of decades of extremely prolific work that yielded 21 novels (two of which remain unpublished, written in joual, the Quebecois French that Kerouac grew up speaking), 11 books of poetry, and various essays, works of non-fiction, letters, journals, recordings, and one short film. There’s still a whole legend beyond On the Road to be discovered.

* * * *

Kerouac was more than Sal Paradise — he was Ray Smith, he was Jack Duluoz; he was a little boy watching his brother die of rheumatic fever, and who didn’t speak English comfortably until his late teens; he was the man who went to Columbia University with a football scholarship and wrote sports articles for the student newspaper; and, yes, he was also the man on the road with Neal Cassady, passing a joint back and forth as the white lines passed swiftly underneath them and San Francisco or Denver or New York glittered up ahead. He climbed mountains, hitchhiked, wrote, suffered, prayed, lived with his mother for far too long, and got violently drunk far more often than he should have. He was, in a word, complicated. And it reflected on the page.

“My work comprises one vast book like Proust’s Remembrances of Things Past except that my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterward in a sick bed,” reads a short paragraph before the text of Big Sur and the rest of the Duluoz Legend novels. “In my old age I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy.”

Instead, Kerouac died in 1969 in St. Petersburg, Florida of a sudden internal hemorrhage caused by cirrhosis and an untreated hernia, the result of a bar fight he’d been in a few weeks earlier. He was 47 years old.

Toward the end of his life, Kerouac was increasingly reactionary and anti-Semitic, a right-wing conservative with the polar opposite of the ideals and morals he’d represented for most of his life: there’s no denying that the man had faults and that those faults compounded as he aged. But not having a clear and calculated vision for his work was not among them. To do that vision justice, and to really get an idea of who Kerouac was beyond Sal Paradise, it’s worth it to read a few more of his books. And there will be no need to say another word.

This post may contain affiliate links.