Some perfectly reasonable people do inexplicable things on the Internet. A great aunt punctuates every thought dispensed through Facebook with “wheeeeeeeeeeeeee,” a former professor conveys even mundane, emotionless missives in all caps. In parsing these phenomena, I usually put totally bizarre behavior down to a digital native vs. non-native difference — a problem with bridging the gap between the world we live in and the world we live on, a failure to grasp the realness of the net. But there are all kinds of Internet weird — over-sharing weird, smiley-face overpopulation weird, for example. We’re all always learning how to be on the Internet, our online existence a continuous give and take as we adjust to our software, and as it adjusts to us.

Some perfectly reasonable people do inexplicable things on the Internet. A great aunt punctuates every thought dispensed through Facebook with “wheeeeeeeeeeeeee,” a former professor conveys even mundane, emotionless missives in all caps. In parsing these phenomena, I usually put totally bizarre behavior down to a digital native vs. non-native difference — a problem with bridging the gap between the world we live in and the world we live on, a failure to grasp the realness of the net. But there are all kinds of Internet weird — over-sharing weird, smiley-face overpopulation weird, for example. We’re all always learning how to be on the Internet, our online existence a continuous give and take as we adjust to our software, and as it adjusts to us.

Back in 1995, when email was beginning to seep into day-to-day communication, a set of guidelines for “the Internet community” was published by the Intel Network Working Group. What constantly emerges throughout this early attempt at coding behavior is a reminder to users that although online communication might take place in a weird world of blinking lights and flickering screens, it is fully a part of the world we bump around and breathe in.

The working group reminds us “…people with whom you communicate are located across the globe… Give them a chance to wake up, come to work, and login before assuming the mail didn’t arrive or that they don’t care.” They suggest we “remember that the recipient is a human being whose culture, language, and humor have different points of reference from your own.”

I am not old enough to have really known life pre-Internet. There was never a time when it didn’t seem natural that I would be able to send an instantaneous e-message to someone on the other side of the planet. Maybe this “netiquette” education reveals something of the process of adjustment that my elders went through.

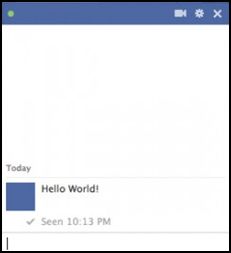

But even if these cognitive gaps have been bridged as virtual and actual slip into more or less comfortable symbiosis in contemporary life, the most minute changes to our various interfaces can still require significant shifts in behavior. For example, about six months ago Facebook started indicating to users the precise time a message had been clicked on and seen by a recipient, evoking the distinct feeling of being watched, with behavior that once remained safely unseen becoming fully observable.

Although the Intel guide says “Always say goodbye, or some other farewell, and wait to see a farewell from the other person before killing the session,” as chat etiquette has actually developed, it is basically acceptable to disappear mid-conversation. Chat poses a constant negotiation of presence and absence. It’s ostensibly immediate but built on the invisibility of the interlocutor. Chat is about half-presence, half-engagement. I’ll chat with four people while also attempting to write this very blog post. I’ll engage intensely for 45 seconds, and then disappear for ten minutes. I understand this as my right, and it’s what I expect from others. But it also requires a little but of illusion, and the Facebook “seen at” feature potentially disrupts this illusion.

I could be off washing dishes, buying groceries, having just accidentally left my computer open in my room, my Facebook light deceivingly green. I’m not ignoring you. Of course not. These are the comforting assumptions that hold up our online relationships. Now “seen at” forces me to adjust my behavior. Facebook chat becomes like a playground game of hot lava. Those blinking boxes must not be clicked on, the illusion of absence shattered, and presence unmistakably registered.

Facebook is watching me, but I’m keeping an eye out too. This twisted dance is life now. Back in 1995, the Intel Network Working Group thought that maybe if they just got everything all ironed out at the very beginning, interaction on the web would be simple, straightforward, and civil.

“Wait overnight to send emotional responses to messages,” they implore. If only it were that easy.

This post may contain affiliate links.