“Mr. Wolf said he would remember his nephew, who had written in the past about battling depression and suicidal thoughts, as a young man who ‘looked at the world, and had a certain logic in his brain, and the world didn’t necessarily fit in with that logic, and that was sometimes difficult.'” –The New York Times

“Mr. Wolf said he would remember his nephew, who had written in the past about battling depression and suicidal thoughts, as a young man who ‘looked at the world, and had a certain logic in his brain, and the world didn’t necessarily fit in with that logic, and that was sometimes difficult.'” –The New York Times

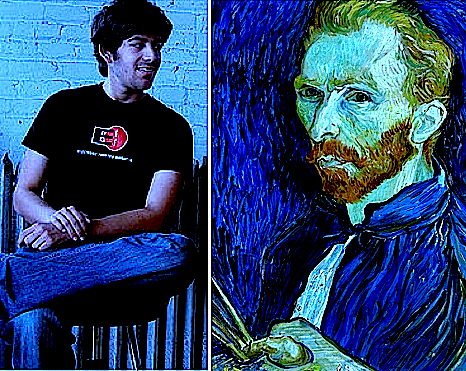

Aaron Swartz, a digital activist and Internet prodigy who helped invent RSS feeds and liberated the bulk of the JSTOR library, is in the process of being thoroughly eulogized by friends, family, journalists, and admirers in the days following his suicide. He suffered from chronic depression and died at 26.

How do we talk about the death of someone special who also battled some form of mental illness? What does it say about our society, about us?

I was struck by something Rick Perlstein wrote about Swartz in The Nation, “I remember always thinking that he always seemed too sensitive for this world we happen to live in, and I remember him working so mightily, so heroically, to try to bend the world into a place more hospitable to people like him,” and Perlstein thankfully continues, “which also means hospitable to people like us.”

Perlstein is saying Swartz envisioned a more humane world — one that he tried to realize himself, no less — but he’s also saying that his unconventional vantage somehow doomed him from the start.

I flashed back to the book Humboldt’s Gift, Saul Bellow’s epic tribute to his late friend and mentor, Delmore Schwartz. In the book, Humboldt, who stands in for Schwartz, is all memories and legacy, deceased from page one. He never stood a chance, Bellow seems to say. The narrator, a version of Bellow named Charlie Citrine, spends the book trying to decide whether to humanize, romanticize, or psychoanalyze the poet and intellectual who was dogged by mental illness.

Humboldt is both an archetype and a uniquely frustrating individual. He is Schwartz, according to several accounts. But Citrine laments that, as far as society is concerned, Humboldt is also “Edgar Allen Poe, picked out of the Baltimore gutter,” “Hart Crane over the side of a ship,” “John Berryman jumping from a bridge,” and every other tragic poet who gets one of those “mad-rotten-majesty pictures” in the New York Times when he “plows himself under.” It makes sense to equate experiences that are similar. Broadly speaking, Humboldt’s manic-depression is Jimi Hendrix’s classic Manic Depression; an independent, incisive friend’s transformation into a self-described “emotional toddler” is Aaron Swartz’s “streaks of pain…running through your head.”

The tragic/extraordinary archetype helps us understand the many creative, charismatic, talented people who have battled chronic depression, manic-depression (now referred to as bi-polar disorder), schizophrenia, or some other condition we label as mental illness. And yet, each of these people is oddly dehumanized when recalled as some inevitable force of nature, at once regarded as Superhuman Phenomenon and Uncontrollable Catastrophe. The message is clear: they were not meant for this world.

Bellow (via Citrine) takes issue with the conflation of wildly different personalities and intellects. Is it because he is determined to acknowledge each unstable talent as an individual, a human being? What does he find so infuriating about society’s instinct to martyr its creative and mentally unstable?

Bellow’s argument is that by martyring our ‘poets’ (which we can extend to mean ‘visionaries’), we let ourselves off the hook:

“The country is proud of its dead poets. It takes terrific satisfaction in the poets’ testimony that the USA is too tough, too much, too rugged, that American reality is overpowering…So poets are loved, but loved because they just can’t make it here. They exist to light up the enormity of the awful tangle and justify the cynicism of those who say, ‘If I were not such a corrupt, unfeeling bastard, creep, thief, and vulture, I couldn’t get through this either. Look at these good and tender and soft men, the best of us. They succumbed, poor loonies.’”

Bellow’s book does not aim to lionize a once great, tragically disturbed figure; it aims to earnestly reflect on how to be that person’s friend, both in life and in death, and how to value and continue the work that he started. This book is more about Citrine than Humboldt.

Today, the public can immediately process the death of someone like Aaron Swartz not only through a New York Times obituary, but also through the words of those who truly cared for him. Many are writing about what it was like to stand by him even when he rejected them, as well as offering a litany of the important work he was doing. We don’t have to wait for a biopic to come out ten years hence insinuating that his unfair persecution by the government contributed to his mental state; Lawrence Lessig said that, publicly and emphatically, right away. A petition has been mounted to “Remove United States District Attorney Carmen Ortiz from office for overreach.”

I started reading Humboldt’s Gift on a beach in August. When I got home, still dazed from the sun, I learned of the suicide of another poet and scholar, this one more lucid charm and less hermetic paranoia than the fictional Humboldt; this one my close friend.

My first thought was that I would just have to be that much better; work that much harder to bend the world to her vision.

My next thought, of course, was, “How could I have let this happen?” Because it was not inevitable.

When she was alive, I had also observed that my friend was “too sensitive for this world we happen to live in.” One night, we found a distraught cat on the street looking up at an abandoned building. We followed its gaze to three other cats in a window, comically looking down at their friend, who had apparently fallen. We couldn’t get into the building, nor was there anyone to call. My other friends and I were happy to admit that there was nothing we could do and continue on our way, but she could not be satisfied with that. She wanted to adopt the cat. When we insisted that she leave it alone, she fell into a melancholy that no one could coax her out of for the rest of the night. “Every living thing needs to be touched and loved,” she said.

I do not have a problem with comparing different people’s experiences of mental illness; that helps us to understand. I do take issue with conflating different aspects of mental illness when we are searching for a reason why someone took her own life. It may seem romantic to say she was too sensitive for this world, but it was not my friend’s deep empathy that made her kill herself (she managed to cope with the cat incident). Nor was it her position that social justice was worth fighting for. And it obviously was not her magnetic charisma, intelligence, or ability to get things done.

It was literally and specifically the chemical imbalance that is unfortunately sometimes associated with a distinctive outlook and above average abilities. I cannot speak about Swartz, but I don’t think of my friend as a martyr. She was empowered when she fought for something she believed in; she was poetic when something tangible in the world saddened her; and she was only sometimes dangerously self-destructive when she was having a depressive episode.

Depression, like other mental illnesses, often manifests as an irrational episode, rather than a permanent condition. This is important to acknowledge. Swartz described his own depression in this way in a blog post from 2007. “Everything you think about seems bleak — the things you’ve done, the things you hope to do, the people around you. You want to lie in bed and keep the lights off. Depressed mood is like that, only it doesn’t come for any reason and it doesn’t go for any either,” he explains.

Swartz goes on to repeat the often cited figure that depression affects one in six people in the US and to acknowledge that it is a condition that can and should be treated. He writes, “Sadly, depression (like other mental illnesses, especially addiction) is not seen as ‘real’ enough to deserve the investment and awareness of conditions like breast cancer (1 in 8) or AIDS (1 in 150).”

It’s never anyone’s fault when someone commits suicide. That said, a lot of people who struggle with things we can only try to imagine also contribute things to the world we cannot afford to lose. So, I prefer not to think about the tragic/extraordinary figure as a force of nature that we cannot approach or reckon with.

Rather, as many of those who knew Swartz are doing, we need to think about how to be that person’s friend, both in life and in death. To me, that means assigning people to keep constant watch when they are vulnerable; removing them from a situation that is taking a toll on their mental health whenever possible; and never letting their mental condition belie the true value of their genius, which can only be realized when it is put into practice.

This post may contain affiliate links.