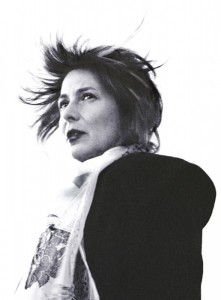

It has been over 15 years since Chris Kraus published her first book, I Love Dick, an epistolary novel that weaves art criticism and philosophy together with a story of unorthodox, unrequited love. But the influence of that work on a generation of writers has become particularly evident this year, with the publication of new books of fiction-criticism and memoir, such as Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? and Kate Zambreno’s Heroines.

Kraus, who is also a filmmaker, art critic, and editor of the Semiotext(e) Native Agents series, is a writer whose work expertly performs simultaneous, potentially incongruous functions. Her most recent novel, Summer of Hate, is both a suspenseful love story and an exposé of the criminalization of poverty in Bush-era America. Like her fiction, Kraus’s writing on art (such as that in her 2009 essay collection Where Art Belongs) is full of life and thrilling to read, marked by an embrace of the world as it exists. Kraus’s work is a rare space where art, politics, theory and feelings are all tied up together because, as she continually makes clear, they are always all tied up together.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Kraus recently about her newly published monograph on participant art, Kelly Lake Store & Other Stories, the absorptive potential of the art world, Summer of Hate, and why it’s important for people in the creative industries to talk about money.

Helen Stuhr-Rommereim: To start, can you define “participant art” of the kind that you talk about in Kelly Lake Store & Other Stories and your book Where Art Belongs?

Chris Kraus: “Participant art” is a phrase that’s been used a lot during the past year in the art world, to describe the huge range of projects that somehow engage with real life. Like the ones at last summer’s Documenta. Projects that could be equally at home in other disciplines — geography, journalism, public planning. But these fields have so little glamour in the larger world! The glamour comes from the art world. It seems as if people are drawn to the art world because it gives meaning and volatility to activities that are interesting, but would otherwise seem insignificant.

With the Kelly Lake Store project, you applied for a Guggenheim to invite MFA students to work in closed down general stores in a small town in Minnesota, and included their response in your essay. Were you surprised that your proposal was rejected?

That was a joke. As soon as I got that email from the Guggenheim foundation, I knew I’d be using it somehow. Even applying as an artist was ridiculous. I’m not a visual artist, but at this point the distinction between visual arts and humanities has pretty much disappeared. The fact that their rejection of the proposal seems so off-base says something about how much definitions of visual art have changed.

You move toward an idea of art as a refuge for practices and ways of living that are somehow not viable anymore in the larger world. Doing creative work in a small town itself becomes something radical. How has that happened?

I’ve thought that for a long time. All these disciplines, like underground/experimental film, have migrated into the art world as the culture industry becomes more hegemonic. The same goes for sound art and literary fiction. Like other writers, my work is discussed more within the art world than the literary world. The art world becomes this incredibly large frame that basically encompasses any kind of intentional living.

Do you think this shift has coincided with a narrowing audience for, for example, more experimental fiction?

I think it’s true of literary fiction in general.

In the Kelly Lake Store essay, you quote New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz writing about “post art” in the context of Documenta, and point out that he can’t talk about it outside this object-based discourse — asking how it is making meaning, etc. How should a project like Kelly Lake Store be talked about?

Ah, I was just trying to take a dig at this kind of mindless boosterism. But you’re right — if these “participant” projects share none of the values of visual art, how can we talk about them? But art criticism is always devising new narratives, new trajectories to place people’s work in. Writing about art, I’ve always had this sense that art isn’t a given. It’s very mutable, and redefined all the time, and best by those who are making it. That is what interests me largely, is to consider these people and how they are doing it. Every artist is inventing their own work, their own place in a continuum.

Can you talk about the idea of failure a little bit? It’s something that runs throughout the projects in Where Art Belongs, and your essay on the Kelly Lake Store begins with a rejection letter. Even I Love Dick is in some ways an elaborately semi-failed sexual conquest. Is it important for a creative project to absorb the possibility of failure?

I don’t see any of those situations as failures! The dissolution of the L.A. alternative space Tiny Creatures, whose history I chronicle in Where Art Belongs, didn’t mean the project had failed. I mean, what’s the alternative? That this group of people who met in their twenties would stay together for the rest of their lives? People come together for a moment of time, things are created and then they shift, and people move in other directions. Building permanent institutions isn’t necessarily the most worthy goal.

In I Love Dick, the main character is named Chris Kraus, and in subsequent books the main characters share many identifying qualities with you, Chris Kraus. Is it fair to say that almost all of your fiction is drawn directly from your life?

Yes, that’s true, but I don’t think that’s the most important or interesting thing about my writing. Most literary fiction is intimate, connected to the writer’s life in some direct or lateral way. Completely invented stories are more the terrain of genre fiction, where it’s all plot.

What is the spark that makes you want to write a novel?

When I began writing I Love Dick, I knew it would take three books to cover the material – basically, my life to that point and the life of the late 20th century art and intellectual worlds. So that was a pretty big spark. Aliens & Anorexia and Torpor followed on from I Love Dick.

But Summer of Hate is a departure, it’s not part of that body of work. The mid-2000s, the height of the Bush years and the war in Iraq, were excruciating. I was in the Southwest U.S., and directly experiencing the petty cop dramas that mark underclass life. I started writing some non-fiction pieces, kind of as place holders, until I was ready to figure out what the novel should be. When I finally did, it became clear that the novel would have to pivot around the meeting of Catt and Paul, their disparate world. The love story would be the motor, rather than reportage of political events.

Summer of Hate addresses a lot of important, often neglected, issues, like incarceration and the criminalization of the poor, and it was clearly important to you that you address them. But this topical imperative is always fully intertwined with the story. How do you approach weaving these threads together?

What I most wanted to convey in this book was the psychic experience of underclass life in the U.S. What is it like to have no culture? Media culture has pretty much replaced any regional or working class culture. The people I describe in the book are vacuumed out, deprived on the most cellular level. Within that world, you’re either an evangelical Christian in a twelve-step program or you’re an addict, in and out of jail. Through Paul’s character, I tried to convey what it would be like not to see the world through the associative chain that culture provides, but to see each thing separately. A terrible aloneness.

Catt asks this question in the novel, with reference to Paul: “But what can it be like to be that intelligent and have no information.” It’s a striking question.

Yes. And very depressing. Really, the work I’ve done in the past year with Mexicali Rose was a reaction to this. I was blown away by the extent to which a popular culture and shared frame of reference still exists in the Pueblo Nuevo community, just three hours away from L.A. Seeing the work that Marco Vera, Fernando Corona, Israel Ortega and other artists are doing there was very inspiring.

Is there a way to foster that kind of community and community culture, to try to build it from scratch?

No, that wouldn’t be right. That’s kind of the problem with the whole non-profit ethos in first world culture. You know, “community-based art”? Who wants it? It sounds phony and missionary. In Mexicali, the community is already there.

It has to do with how people are positioning themselves, one to another.

Yeah. There’s a great line in Proust: “Any human altruism which is without egotism is sterile.” If people aren’t advancing their own ideas and personas, there’s no excitement.

In Summer of Hate there is this dynamic of Catt and Paul on two sides of the line of being OK and not being OK. Catt is always essentially OK, and Paul is more or less not OK. They form an unstable bridge across this divide.

Yeah, that’s so true. In Paul’s background, there’s so much psychic damage that stability is almost impossible. Just when he’s almost out of the woods with court and police problems, and enrolled full-time in school, he dumps her for a cutter. Did you ever read about the marshmallow study? Psychologists sampled a number of five-year-olds from different class backgrounds, who were given a marshmallow and told they could either eat it now, or save it for 30 minutes and receive a bonus marshmallow. None of the lower-class kids could do this! Already, their brains are so hard-wired towards unfulfilled need, they can’t exercise the middle-class discipline of delayed gratification.

You talk about money a lot more than most people involved in the arts tend to, especially within actual writing and criticism. Why do you think it’s important to talk about that unglamorous, practical stuff?

Most of the people in the art world are rich, or at least upper-middle class. I think it’s important to maintain a transparency about how one actually supports oneself. Often, an artist or writer working without any other means of support is being supported by other means, elsewhere. But envy kicks in, and others believe that the person is a “better” artist, or at least making work that’s more financially viable. And this isn’t true. Very few people are able to support themselves through the proceeds of their work alone. There’s support from academe, through a teaching job, or family money, or spousal support. I chose to support my work partly by buying and operating low-end residential real estate.

Keith Gessen talked about this on an n+1 panel about money. He disclosed the advances he’s received for his books, and the advances his friends have received. A New York fiction writer receives a six-figure advance; a Russian poet he’s translating receives $8,000 that must cover the cost of translation. Rather than compete against each other, it’s interesting to examine how creative work is valued. Entry into the art and intellectual worlds is very limited to people who don’t have independent means.

There seems to me to be an expanding interest in your writing at this particular cultural moment. Why do you think this is happening now?

Oh, I’d like to think it’s for more elevated reasons, but really I think it’s because I Love Dick has been circulating again, at a moment when there’s a kind of critical mass of other female writers engaging with the same questions of privacy, confession, etc. Even though the narrator of I Love Dick is about to turn 40, she’s revisiting her adolescence and early twenties, and there’s a great appetite for the coming of age novel! My hope is that this interest can expand to my recent work, and current interests, which have been less about gender and more about space and time in different parts of the world.

As an editor at Semiotext(e) — the publishing house responsible for introducing French Theory to the United States — and as someone who incorporates critical theory into their writing in all kinds of straightforward and not-so-straightforward ways, what do you think is the importance of critical theory to culture at large, and to people and their lives?

Reading theory, like reading poetry, is exhilarating. Semiotext(e) has always believed in presenting theory brut, the primary texts, without too much commentary. The experience of reading theory is very close to the experience of looking at art . . . a great, expansive high. I just inhale these texts and these ideas, and they really become a part of my experience, and it gets manifested in what I write. The theory writing within I Love Dick and Aliens & Anorexia came from the readings of certain philosophers that were fueling my delirium at that time. The poetic charge you get reading theory, that’s the best reason, the best way to explain the continued attraction to theory among artists. Of course theory can be co-opted and be used as the Law, something very programmatic. But that’s not what we do.

This post may contain affiliate links.