You know how it’s okay for you to make fun of your siblings, but it’s totally uncool for anyone else to take a jab at them? This is more or less how I feel about my much-maligned generation. So my sisterly hackles rose as I read Christy Wampole’s Saturday New York Times Opinionator column “How to Live Without Irony,” which is a rather reckless attempt to tear down the perceived culture of an ill-defined group of “Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s.”

You know how it’s okay for you to make fun of your siblings, but it’s totally uncool for anyone else to take a jab at them? This is more or less how I feel about my much-maligned generation. So my sisterly hackles rose as I read Christy Wampole’s Saturday New York Times Opinionator column “How to Live Without Irony,” which is a rather reckless attempt to tear down the perceived culture of an ill-defined group of “Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s.”

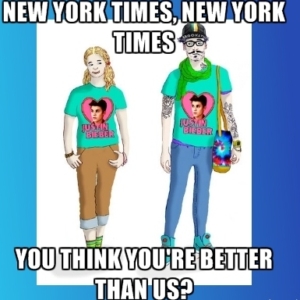

The article is so grating to my twenty-something ears that it’s easy to imagine there’s some truth to David Roth’s joking tweet, which suggests the Times posted Wampole’s piece exclusively for trolling purposes. If this were the case, silence would be dignified; since it’s probably not, I’ll indulge in a few indignant words.

Wampole tackles “irony,” a word she never defines, by tacking it, in her opening sentence, to “the hipster,” that enigmatic figure whom she vaunts as “the archetype” of our age.

Bold words, hers.

Concerning words: As a member of the generation under investigation, I very much hope not to be judged by the caricatured and outdated archetype of “the hipster” that Wampole gleefully draws.

Puzzling words: Didn’t the twee tense choice in the title of n+1’s 2009 conference and 2010 book, What Was The Hipster?, essentially forbid us from ever talking about “the hipster” un-ironically (sorry) again?

Indeed, the old-fashioned feel of Wampole’s article is perhaps what’s most surprising about it, given that Wampole was born in 1977, just three years before the oldest of the generation she’s bemoaning and ten years before me. This piece might have been interesting and provocative (in a good way) in 2005, or even early 2008, when people were still trying to figure out what the deal was with all the PBR-swigging rich kids moving to Williamsburg.

But Wampole’s contention that “irony is the ethos of our age” crumbles dramatically when you consider the first election of Barack Obama, who in 2008 ran on an entirely un-ironic platform of “hope” and “change.” His message was swallowed whole by hordes of young people, including “the hipster,” who canvassed and voted in record numbers and helped ensure the president an easy victory.

And what happened a couple years later, when hope seemed to be fading and change was too slow in coming? Did the hipster fall back on “cultural numbness, resignation and defeat,” as Wampole would have it?

No. He/she/it flooded into Zuccotti Park in Manhattan or wherever else around in the country to engage in that least-ironic of activities: activism. You can call the Wall Street Occupiers a lot of unsavory things, but “ironic” isn’t one of them. These people wanted change so badly that they massed together for weeks on end without any clear idea of exactly what change they wanted.

They gathered with such enthusiasm, in fact, and so easily accepted each others’ vague goals as their own, that it’s easy to imagine they might have had another motive in joining Occupy — namely, to join something. That’s right: forget “foraging for what has yet to be found by the mainstream,” as Wampole would have it. “The hipster” flocked in droves to a movement that was forcefully calling itself “the 99 percent.” You can’t get much more mainstream than that.

This leads me to a point about the eccentric hipster fashion, which seems to irk Wampole more than any other characteristic of the species. According to her,

“this contemporary urban harlequin appropriates outmoded fashions (the mustache, the tiny shorts), mechanisms (fixed-gear bicycles, portable record players) and hobbies (home brewing, playing trombone). …He is a walking citation; his clothes refer to much more than themselves.”

First off, as any good Judith Butler-citing hipster knows, all clothes “refer to much more than themselves.” That business suit you wear to the office? It’s referring to an predetermined image of professionalism. The high heels? An image of sexiness. The tweed jacket? An image of the academy. Of course, not even Butler puts this better (cover your ears, sincere folks! A pop culture reference cometh!) than the fashion editor Miranda Priestley embodied by Meryl Streep in “The Devil Wears Prada.” Every item of clothing we don, she reminds us, is a nod to the tastes of others.

But is there a difference between projecting professionalism and projecting, say, a 1950s waitress? Wampole, when she gets to her leaden prescriptive phase, seems to think so. Here’s part of her list of self-help questions:

“Look at your clothes. What parts of your wardrobe could be described as costume-like, derivative or reminiscent of some specific style archetype (the secretary, the hobo, the flapper, yourself as a child)? … Do you attempt to look intentionally nerdy, awkward or ugly? In other words, is your style an anti-style?”

(To answer personally, for a moment, I can’t help noting that any “attempt” I make is, by definition, “intentional.” But as it happens, no — I don’t “attempt” to look nerdy. I do it without trying, and often against my best efforts. Must I still submit to flogging?)

But rather than pillory those with taste and time enough to pull off “the secretary” or “the hobo,” why not ask why these hipsters are intent on doing so? I have a pet theory. My generation came of age in a period of dramatic cultural flux: not only did we experience a more racial diversity in classrooms and in the media than previous generations, but we were possibly the first generation taught to criticize the idea of a dominant culture. In school, we sang Christmas, Chanukah, and Kwanzaa songs with equal fervor; outside, the Jewish kids ate more pad see ew than latkes and everyone watched Urkel in “Family Matters.”

We were incredibly lucky to have such an upbringing. But with the erosion of a dominant American culture (white, Christian, heterosexual) came the erosion of a common cultural memory. Our families’ pasts bore no resemblance to the pasts of our friends’ families, and our daily public lives did not bear strong traces of tradition. Any sense of the realness of the past was scrubbed from our lives.

Is it any wonder that some of us tried, in early adulthood, to reclaim (horrible hipster word!) some sense of the past and make it our own? And are we really harming anyone by channeling the past via clothing? Or are we just trying to relate to a past era in the same way Occupiers tried to relate to all Americans?

Surely, decades from now, we will look back at the clunky glasses and the skinny jeans and the shaggy mustaches and the mustard skirts and the neon socks and we will wince and giggle at our own youthful ugliness. But we’ll feel nothing more awful than the wistful nostalgia (horrors!) that plagues survivors of the 1970s and ‘80s when they’re forced to look at old images of themselves in full perms, frosted eye shadow, and denim jackets. Sure, the clothes were bad, but they didn’t bring down civilization.

Wampole seems to think ours might:

“This ironic ethos can lead to a vacuity and vapidity of the individual and collective psyche. Historically, vacuums eventually have to be filled by something – more often than not, a hazardous something. Fundamentalists are never ironists; dictators are never ironists; people who move things in the political landscape, regardless of the side they choose, are never ironists.”

Setting aside the fact that Wampole has changed her tune over the course of the article, having claimed earlier that “every category of contemporary reality” exhibits irony, including “politics,” Wampole seems to be making the very serious claim that a culture of irony leaves us vulnerable to a Fascist takeover. This strikes me as unlikely. If anything, as Occupy demonstrated, my vain generation is extremely interested in playing a key role in history and would therefore rise up passionately against the threat of dictatorship. (Our obsession with history is also, perhaps, why we nostalgize photographs so quickly — but Jennifer Egan and Stephen Colbert have already fully covered this territory, as Wampole doesn’t note.)

She feels free, though, to diagnose our generation’s irony as a symptom of the fact that we are not “people who have suffered.” And it’s true that, despite the mild irritations of a bombed-out economy and dizzying unemployment rates and sky-high student debt and a stagnant government and the threat of climate change, we’re doing okay. We haven’t lost half our population in a total war or a massive epidemic. We’re nothing like Hemingway, for example, who saw out a couple gruesome wars and suffered from paralyzing depression and alcoholism and whose literature, with its clipped sentences of dramatic understatement, is arguably the most compelling exploration of “irony” in 20th century fiction.

Irony, it seems, can flow from many emotional sources.

What’s really insulting about Wampole’s piece isn’t that it flogs the character of “the hipster,” for whom I have no particular affection (he has laughed in my face at least once, cast me a number of withering stares, and most often simply ignored me). What’s insulting is that she didn’t take the time to form an original or even contemporary argument about contemporary culture, and with the exception of a personal friend she neglected to cite any of the thinkers on whom she must have relied, assuming she did any research at all. Professor Wampole, I’m sure you’re a brilliant scholar and wonderful person. But next time you want to write about contemporary culture, try engaging with it first. Until then, pick on someone your own age.

This post may contain affiliate links.