I do whatever I want

and whatever I say, goes

I don’t have a throne or a queen,

nor anybody who understands me

but I still remain the king…

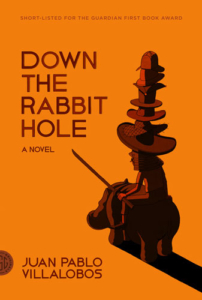

…So goes “El Rey (The King),” a punchy mariachi song oft referenced in Juan Pablo Villalobos’s punchy debut novel, Down the Rabbit Hole. One may presume that “The King” of this novel is Yolcaut, a drug baron about to take over a prominent cartel. In fact, that royal moniker belongs to his son, this story’s eponymous narrator, the seven-year-old Tochtli (Nahuatl for “rabbit”).

Tochtli is precocious, so much so that he staunchly states it in the very first line. Indeed, Tochtli is obsessed with telling us what he knows, perhaps in attempt to prove his worth as a narrator. He proceeds to list some of his favorite words, such as “sordid, disastrous, immaculate, pathetic, and devastating.” However, poor Tochtli betrays his youth as the novel wears on, incorporating these words throughout until they become not only misappropriated and jangling to the ear, but also completely meaningless. Sordid, pathetic Tochtli is completely unaware of the limitations of his perspective, and these keep him in a prison of his own ignorance.

Little Tochtli reaches out to us from a secluded mountain lair that he calls his “palace,” tucked away in the far reaches of Honduras. He leads a fairly routine life under the tutelage of the palace’s private instructor. Tochtli often regurgitates select trivia about hygiene, food safety, and the care of exotic creatures that he’s gleaned from his tutor.

Yolcaut tries to keep his son in the dark as much as possible, placating him with endless gifts of extravagant headwear, samurai swords, and, after a tireless search, two Liberian pygmy hippopotamuses. Time and time again, Tochtli, like “El Rey” of mariachi fame, does and gets what he wants, all to fuel his innocence. But Yolcaut’s efforts are in vain. The King can’t be kept in the dark for long.

Villalobos’ chosen viewpoint is potentially restrictive, but more often than not he employs it to the most chilling effect. Tochtli’s naivety lends itself to dramatic irony, which in turn lends a lightheartedness to the story, swaddling us in complacency until we catch brief glimpses into Tochtli’s cruel reality, including nonchalant references to closed doors hiding enormous bounties of ammunition, cocaine, whores, and even wild animals kept in captivity.

Villalobos’ dexterity of voice slips, however, when he realizes that at some point the political dealings and overarching operations of the cartel need to be conveyed to the reader. After all, Tochtli hardly knows a soul (he asserts that corpses don’t count as acquaintances.) For Tochtli to get his hands on some more illuminating information logically beyond his grasp, Villalobos overly relies on Mitzli, one of Yolcaut’s many servants. Mitzli happens to be a real nosy parker who, perhaps too conveniently, loves to tell Tochtli about the more mature hearsay whizzing around the palace, about treason, about the Honduran government, about the prostitutes that disappear with Yolcaut behind closed doors. Mitzli’s tongue flaps so freely with gossip that we wonder why Yolcaut has not yet cut it off.

Nevertheless, this small improbability hardly derails Villalobos’s concise, diminutive first novel, which packs a wallop with every word. Its pocketsize stature, a slim 75 pages, is deceptive (indeed, the first word that sprang to my mind was “cute”). But, like its pintsize narrator, this novel divulges an unnerving inner darkness beyond its dainty exterior. Once again, translator Rosalind Harvey proves her expertise in crafting an English rendition of misleadingly cool, calm, and collected narrators who disclose their vulnerability only in small hiccups (also evidenced in Enrique Vala Matas’s Dublinesque).

Because this is Villalobos’s first foray into fiction, it seems easy to discount Down the Rabbit Hole as a mere literary exercise in unreliable narration, a simple experiment in the up-and-coming genre of “narcoliterature” taking the Latin American writing community by storm. But the tragedy of this story stems not from detailed accounts of drug mules or assassinations in cold blood. The reader’s heartbreak comes when Tochtli’s untenable barricades, those he has tried so hard to fortify, come crashing down around him. His palace becomes a pit of filth. He is no king. He’s just a boy.

This post may contain affiliate links.