The work of Chris Ware is deeply sad; I say this as a devoted and faithful reader. Beneath the Edward-Hopper-colored strips, within the fine print that constitutes 95 percent of his lettering, floating around the edges of the beautifully drawn cursive words and phrases that take us from one scene to another, is despair. But, fortunately, the good kind: the kind that creates room for complex and touching narratives, narratives that can encompass both the weirdest, most cringe-inducing personal moments and hyperspace rushes into a macro-perspective that locates a figure’s life within a larger city (usually Chicago) and even a larger world. Be the character a hapless bee, a mouse, or a neglected son enchained to a neglected father, the same note of solitude always strikes at the end of a book, so much so that solitude becomes a kind of form that Ware perpetually tests the edges of. In his most recent book, Building Stories, even a building gets its chance to express sadness, as it comments on the lives of its inhabitants. What keeps me coming back, and what makes this work so remarkable, is the soul running through it: in characters’ wizened faces, in their faintly plump bodies, and in the all-too-believable nuances of their dialogues and monologues. This is humanity.

And on top of that, there’s the packaging. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

The main character of this book — or the person who reappears the most, in the web of semi-related characters floating throughout — is an amputee who lost her right leg below the knee after a childhood boating accident. Somehow, this is perfect. No glorifier of egotism, Ware makes our guide through the Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise of this book (not in that order) someone who must cope perpetually with disfigurement, who can never forget her humanity and whose humanity we can’t really ignore. When we meet her, she’s in her early twenties, living by herself, dating occasionally, meeting the sorts of schlumpy creeps one might meet in a comic strip version of life — or real life, whatever the difference might be. Gradually, she finds someone she’s comfortable with; they settle down, have a child, and move to the suburbs. Is she happy, or isn’t she? This is the question that keeps being batted back and forth, subliminally, and to which we get changing answers. Though her stooped posture throughout is not the typical stance of a “happy” person, this book comes close to suggesting that perhaps it is.

The narrative is laid out with Ware’s characteristic jumps, digressions, text enlargements, and yet the timelessness of the stories being told maintains integrity despite these potential sources of erosion. We also learn, in fairly short order, the life of the tenement in which the main character lives when she’s younger, because the tenement itself lays it out for us. A brick monolith built from longing, the building lists all the things that have occurred within its depths: its arguments, its orgasms, its deaths, its accidents. It also lusts quietly after people passing by and at times serves as a Greek chorus of one, not so much on the proceedings in the book but on the proceedings of several lifetimes. If the book were a drama, you could say the tenement makes a fairly memorable entrance and then departs. We get another memorable cameo by the main character’s elderly downstairs neighbor; in quick, cruel frames, we watch her life move from a withdrawn youth to a hopeful young adulthood to a crumpled old age, a truly heartbreaking portrayal of loneliness which casts perspective on the more elongated portrayal of her upstairs neighbor. In both the longer storyline and this example of a shorter one, Ware gives a strong sense of containment, of spirits locked up inside unhappy lives, straining. At one point, the main character meets up with an old boyfriend, and the feeling she describes at seeing him is, overall, one of release, of being transported.

The omnipresence of buildings in this book helps with that sense of containment, of a world peopled by so many bound Prometheuses: dark, forbidding, apartment buildings; grand but simultaneously unprepossessing suburban homes, row upon leaf-shaded row; dark, mysterious towers, with only a few tall, narrow windows, all dark; squat-two story buildings with shops on the first floor; ornate civic edifices left over from another era; one-story boxes of uncertain purpose; bland, monochromatic government buildings — all leading to the conclusion that, as we live our lives, we are also moving from one building to another, and the personalities of those buildings shape us, either repelling us or drawing us in. In another sense, though, Ware suggests that we are all a bit like his character Branford, a bee, drifting from flower to flower, “licking the eyes of God,” as he calls it; when Branford repetitively bumps into obstacles because he can’t remember having traveled a certain path before, we can only be reminded of ourselves, bumping into the walls of one house or apartment after another because we can’t remember that what we might have actually wanted was to be free. We do this because we humans are hungry for architecture, of one sort or another; it gives us structure, and it keeps us from going, well, bonkers.

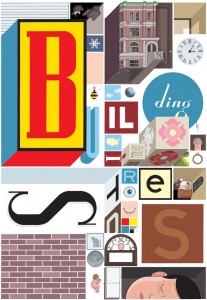

But speaking of structure: it really is time to mention the book’s appearance. It comes in a large, thin, heavy box. It consists of 14 parts. These parts range from relatively tiny, elongated books to a large, poster-sized fold-out board to little booklets to a more traditional comic to a tabloid-sized installment, bound like a magazine. In a sense, this presentation affirms structure and denies it — it reminds us that we like our stories packaged, with pages, but it also invites confusion, and a loss of narrative structure; Ware’s notes on how to read the book call his suggested ordering of them (through a complicated flow chart on the back of the box) “suggestions . . . as to appropriate places to set down, lose, or completely forget any number of its contents within the walls of an average well-appointed home.” When arranged side-by-side, these meticulously designed components resemble nothing so much as a cityscape, with its buildings at irregular heights, themselves imitating the jagged tops of letters in a dense, dark, urban sentence. The packaging, in a larger sense, represents one front of the ever-stormy weather system of American publishing — the “print is not dead by any means” front, as opposed to the “print will soon be replaced by sleekly designed page-less online wonders” front. For what is this but a glorification of the possibilities of print objects? The gesture is hardly new: McSweeney’s Quarterly reminds us of print’s potential with every issue. However, hopefully, works like this will cause the two fronts to meet and generate a snowstorm of reading for reading’s sake, which will obliterate the whole tedious argument.

Attendant dialogues aside, my reward for bearing down on the tight, clenched-teethed print in these strips was a brown-and-gray-shaded revelation of how much pain might lurk within an outwardly stable relationship, or, conversely, the meaning and the solace of true solitude, both present and past lodestones for Ware. And yet, by virtue of its sheer size and expansiveness, this collection of strips is a leap forward from the species of sadness Ware has explored before. Viewed in retrospect, the work reads as if Ware were painting a mural in illustration of a series of philosophical issues: what it means to love, what it means to be alone, what it means to be part of a social construct, what it means to be an inanimate object, what it means to be a city, and even, at certain particularly poignant moments, what it means to be a color. And as such, the title is an understatement: the real story told here is the story of the world, and how we live in it.

This post may contain affiliate links.