When Nora Ephron died, the news set off a small avalanche of pieces by people who were fond of her and enjoyed her work, or who just admired her as a woman who had managed to transform herself into a Hollywood player. What was depressing about most of these tributes was that they confirmed what fans of her early work—her work as a writer—should have realized long ago: that by the time she died, she was mainly thought of, by most people, as a “filmmaker.” A 2000 paperback reissue of her 1975 collection Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women was packaged with a cover illustration of Ephron holding a movie camera, with a bullhorn at her feet.

Ephron may have seen the leap to movies as a natural progression for someone who, as the daughter of a married screenwriting team, had movies in her blood. (Unfortunately, she had bad movies in her blood: her parents, Henry and Phoebe Ephron, worked on such keepers as the film version of Carousel, starring Shirley Jones and Gordon MacRae, and Desk Set, one of the Tracy-Hepburn pictures that the kind-hearted would prefer not to talk about.) Ephron’s nonfiction is plainly the work of someone who grew up in love with the snappy patter and verbal gymnastics of classic screwball romances such as His Girl Friday and the Preston Sturges pictures, but she made only a halfhearted attempt to achieve those kinds of heights in her own movies. By general acclaim, the “best” scene in any of the movies Ephron was associated with was the one in When Harry Met Sally… (written by Ephron, directed by Rob Reiner) when Meg Ryan, playing a proper, rather prim young woman to Billy Crystal’s guy-with-a-capital-grunt, shows how loudly she can simulate orgasm in the middle of Katz’s Delicatessen. It really does sum up the sensibility that Ephron brought to her movies, in that it obliterates the character Ryan has been playing for an hour, for the sake of a showy water-cooler moment and a blunt punch line.

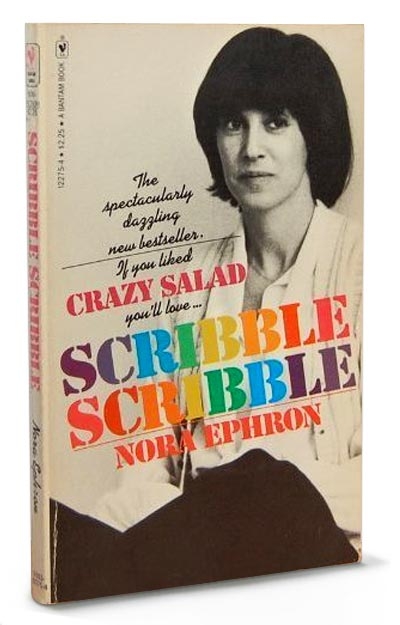

The sensibility that you can see developing over the course of the pieces collected in Wallflower At The Orgy (consisting of reporting that Ephron did for such magazines as Esquire and New York between 1967 and 1970, after having made a name for herself at Dorothy Schiff’s New York Post), Crazy Salad, and Scribble Scribble (which collects the media criticism she wrote for Esquire in the mid-1970s) is both more delicately sensitive and thornier in its skeptical attitude toward the zeitgeist. It’s the sensibility of a woman who is constantly questioning herself and prone to insecurities but who loves being a professional writer, on the hunt for fresh material and racing against the next deadline, in New York when that city was the unquestioned power center for the smart, the funny, and the plugged-in.

Scribble Scribble opens with a brief memoir of Ephron’s time at the Post, where she started working in 1963, and the emphasis on the godawful conditions smack of Rosalind Russell as Hildy Johnson and other newspaper movies and stories in which the reporters take pride in being the ones who have a clear angle on what’s going on in the city, while wearing their status as underpaid social lepers as badges of honor.

The first day I went there, I thought I had gotten out of the elevator in the fire exit. The hallway leading to the city room was black. Absolutely black. The smell of urine came wafting out of the men’s room in the middle of the long hallway between the elevator and the city room. The glass door to the city room was filmed with dust, and written on it, with a finger, was the word ‘Philthy.’ The door was cleaned four years later, but the word remained; it had managed to erode itself onto the glass.

Ephron is quick to add that “None of this was supposed to matter. This was the newspaper business… [And] there was still a real element of excitement to working at the New York Post in 1963,” not because it was a good paper—it was, she writes, “terrible”—but because it had been, once, and Ephron and some of her co-workers believed for years that, at some point, some long-suppressed spirit of civic responsibility inside Schiff would stir itself and she would make real changes, or hire an editor who would. In spirit, this is all very much in the classic The Front Page/ His Girl Friday tradition of swashbuckling accounts of time spent in the trenches of thrillingly irresponsible daily journalism.

The big difference is that Schiff is no irresistible sacred monster or sly dog, like Walter Burns. Ephron gives the impression that she was profoundly disappointed in Dorothy Schiff because she had observed her flirtatious dowager style from a distance and assumed that it was an act she used to manipulate men to get them to do her business, but that when she got close, she saw that it wasn’t an act: Schiff “toyed with” men not because she had any grand design but because she had nothing on her mind besides keeping her ego stroked. “She took everything personally, and at the most skittishly feminine personal level. There was always debate over what made her change her endorsement from Averell Harriman to Nelson Rockefeller in the 1958 gubernatorial election, but the only explanation I ever heard was that a few days before the election, she went to a Harriman dinner and was left off the dais.” Schiff put out an inferior product as a result of her “frothy and giddy” behavior, and the combination offended Ephron as a reporter and as a reader. But as a young writer looking for role models, it also offended her as a woman. “It is taken for granted,” she writes, that Schiff “is a very powerful woman—she is in fact very powerful for a woman and not particularly powerful for a newspaper publisher.” It was the kind of distinction that Ephron, by the mid-‘70s, could be counted upon to make.

Wallflower At The Orgy has some clever examples of what New Journalism looks like at the women’s-magazine level, such as a disheartening account of being given a makeover on Cosmopolitan’s nickel, and several choice samples of late-‘60s snark, dispensed toward the likes of Rod McKuen, Erich Segal, Women’s Wear Daily, and The Fountainhead. (Explaining how she had managed to love that book when she read it at eighteen while completely missing its point, Ephron writes, “It was the first book I had ever read on modern architecture, and I found it fascinating. I deliberately skipped over all the passages about egotism and altruism. And I spent the next year hoping I would meet a gaunt, orange-haired architect who would rape me. Or failing that, an architect who would rape me.”)

The only parts of it that are really dead are the two concluding tributes to the wit and wisdom of Mike Nichols, a noted satirical entertainer then in the process of transforming himself into a slick packager of big, hollow movies designed to be acclaimed in the Arts & Leisure section of the New York Times. These essays have an ominous quality now, and might have that even if Nichols hadn’t directed the first two feature films that Ephron had writing credits on, Silkwood (1983, co-written with Alice Arlen) and the 1986 movie version of Heartburn, Ephron’s self-exploitative, gossipy, best-selling “novel” about her marriage to Carl Bernstein, a book that coarsened Ephron’s talent even as it moved her into a higher tax bracket.

Scribble Scribble has several good stories about media doings in the mid-‘70s and several tart observations on the same, some of which have the special fascination of early eyewitness reports on what it looked like at just the moment when the world started to go to hell. (In a meditation on People magazine, which was a year old at the time: “I had got to the point where I thought I knew what a celebrity was—celebrity was anyone I would stand up in a restaurant and stare at. I had whittled the list down to Marlon Brando, Mary Tyler Moore, and Angelo ‘Gyp’ DeCarlo, and I was fairly happy. Now I am confronted with People, and the plain fact is that a celebrity is anyone People writes about.”) But Crazy Salad stands as Ephron’s liveliest book, because it’s about women—being a woman, individual women, the changing status of women in the workplace and everyplace else—at a time when that subject was enough of a live wire that a magazine like Esquire would want a writer—a woman writer—to tackle it in a monthly column.

She wrote about her feelings about her own breasts, about her sex fantasies (or, rather, her one sex fantasy, “the same sex fantasy, with truly minor variations, [I’ve had] since I was about eleven years old), and about how it felt to have to listen to other women, such as Sally Quinn and Alix Kates Schulman (author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen) lecture her about the incredible hardship of being beautiful; about the Pillsbury bake-off and the development and marketing of feminine hygiene deoderant; about Linda Lovelace, Rose Mary Woods, Pat Loud, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, and Jan Morris, the transgendered travel writer who wrote a winking, twinkly book about her lifelong desire to be a girl, “which I read with a great deal of interest, largely because I always wanted to be a girl, too.” She wrote about the tensions tearing the women’s movement apart from the inside, tensions between heterosexual women and lesbians and between Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem and their respective camps. She wrote about the problems plaguing feminism in this period without proselytizing and without taking cheap shots, as someone who cared deeply about the movement but wouldn’t lie for it. And she wrote about things like porno chic and the Bobby Riggs circus as someone who may have been appalled but was too honest to deny that she enjoyed a good circus as much as anyone.

She also wrote “Dorothy Parker,” a brief, pained essay on something that many more people probably know about than want to discuss publicly: what it feels like to want to cling to a hero figure you know you’ve outgrown. As a woman writer and New York wit, Ephron grew up idolizing Parker. She hung out with other young writers at the Algonquin Hotel and made a game of fitting them into the molds the legend of the Alonquin Round Table left behind: “Victor [Navasky] got to be Henry Ross, Bud Trillin and C. D. B. Bryan alternated at Benchley, whoever was fattest and grumpiest got to be Alexander Woollcott. I, of course, got to be Dorothy Parker… The funny lady. The only lady at the table. The women who made her living by her wit.” Now, looking at Parker’s collected work, Ephron still sees some “first-rate” things in it, but can’t ignore that “the worst work in it is characterized by an almost unbearable girlish sensibility. The masochist. The victim. The sentimental woman whose moods are totally ruled by the whims of men.” Besides which, “One no longer wants to be the only woman at the table.”

Ephron broke away from the pattern Parker set in her life and career. She married happily on the third try, and when she went Hollywood, she was in charge of her own work. That was good for her bank account, and it was probably good for her self-respect, but it’s a shame that the woman who rejected the role of victim didn’t put more of herself into the movies, which never challenged an America in which people of both genders, perhaps especially those with the most power, seemed to enjoying playing the role of victim more than ever. “Dorothy Parker” is included in that 2000 reissue of Crazy Salad—part of the “Modern Library Humor and Wit Series,” selected by Steve Martin—but a lot of other wonderful material was excised, perhaps because of the concerns Martin expresses in his introduction about the passage of time and topical concerns and how “it was necessary to select works whose humor remains intact for us today.”

By then, Martin had starred in what may have been Ephron’s worst movie, Mixed Nuts, but they had something else in common: they were both talented, brainy comic artists who drew back from the idea of reaching above a certain level of smarts and ambition when doing work intended for a mass audience. Martin has spoken in interviews about his decision that it was a pointless waste to make a movie like Pennies from Heaven when most people would rather see Father of the Bride; I don’t know that Ephron ever spoke about it that directly. But I do think it’s hard to read her early books and not imagine what the person who wrote them would have to say about a movie like Michael, starring John Travolta as a sexy, dancing angel, or about the idea that the world was screaming out for a remake of the immortal, shimmering romantic comedy The Shop Around The Corner for the email age, only with Meg Ryan filling in for Margaret Sullavan, and then have a good laugh. Or a good cry.

Phil Dyess-Nugent is a freelance writer living in Texas. He is a regular contributor to The A.V. Club and blogs at The Phil Dyess-Nugent Experience.

This post may contain affiliate links.