Eyal Weizman is the director of the Centre for Research at Goldsmiths University in London, a co-founder of the architectural collective DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency) in Beit Sahour, Palestine, a member of the Human Rights Project at Bard College in New York, and an editor-at-large for journals such as Cabinet, Humanity, and Inflexsions. Whereas such a wide range of activities might lead to a diffusion of thought for some, Weizman’s work reflects an uncanny ability to draw surprising connections from fields as diverse as humanitarian law, Deleuzian spatial analysis, military strategy, and aesthetic theory.

Eyal Weizman is the director of the Centre for Research at Goldsmiths University in London, a co-founder of the architectural collective DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency) in Beit Sahour, Palestine, a member of the Human Rights Project at Bard College in New York, and an editor-at-large for journals such as Cabinet, Humanity, and Inflexsions. Whereas such a wide range of activities might lead to a diffusion of thought for some, Weizman’s work reflects an uncanny ability to draw surprising connections from fields as diverse as humanitarian law, Deleuzian spatial analysis, military strategy, and aesthetic theory.

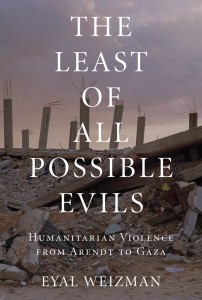

We spoke with Weizman from his home in London on the occasion of the US release of his latest book, The Least of All Possible Evils. The conversation takes up his recent work on “forensic architecture,” the role of the image as a unique form of persuasion, and the importance of how we understand humanitarian crises old and new.

Michael Schapira: I first came across your work in a 2009 BookForum roundtable, “The New Geography,” with Tom McCarthy, Jeffrey Kastner, and Nato Thompson. What struck me about your contribution was the ability to make abstract notions of geopolitical import very concrete through a set of micro-examples, such as the construction of buildings or the staging of legal tribunals. This approach was developed to great effect in Hollow Land and subsequent books. I’m wondering if focusing on these small examples to illuminate broader political or philosophical themes comes out of your training as an architect, and how this kind of thinking maps on to different domains in which you engage, such as legal or political theory?

Eyal Weizman: I would say that my approach to the built environment, to politics and to the law is like that of a forensic architect, which is a subject that I both problematize and develop. This might be so in two senses: the first is obvious — my work on mapping the West Bank and the architecture of colonies was used in international courts, as we were trying to criminalize acts performed on drawing boards.

On the other hand, as a methodology of research I would say that Hollow Land is constructed like a set of archive probes. These two approaches are based on a belief that geopolitics, as well as economic, or military processes, emerges out of a fabric of multiple interactions that can be reconstituted by close observation. As an architect, my attention is naturally directed at material organization and form — sometimes large territorial transformations and sometimes architectural details. Often the two are connected, as new details and technologies exercise large effect. But the relation between the architectural level and larger contextual forces is complex.

I am not sure we can speak any longer about scale though; the analysis of territories does not happen at a different scale than that of a single building block, say, as each is assembled through complex networks and forms of practice that extend far and wide. It is the meaning of its density and intricacies that matter: where does knowledge and material arrive from, what economies do they partake in, what can be assembled by a multiplication of this element, etc.? These multiple ways of unpacking an object or a spatial condition is what poses the greatest challenge to forensic architecture as a form of analysis. Of course, I do not mean forensic architecture in the sense sometimes used to refer to those surveyors doing court work for the insurance industry, but as a mode of analysis that extends the scope of what architecture can do in the world today.

In Hollow Land I discussed the transformation in the use of Jerusalem stone over the modern history of the city. It shifted from being a structural element used in 40-30 cm blocks in the Ottoman period to being a mere cladding detail of about 5-7 cm today. This happens through a set of legal transformations that take place during the British, the Jordanian and the Israeli occupation periods. When the city expanded — also into occupied territories — the stone cladding, mandated by law within the city, started to mark out its shifting boundaries. Serial type concrete-structured homes in neighborhoods far away from the historic city in areas annexed to it could now be presented as part of the ‘holy city’ of Jerusalem.

I can’t get into more detail regarding this example now, but this is just to say that it might demonstrate the kind of connections unfolded by following the networks of relations folded into materiality. The observations in Hollow Land are mostly structured around such readings. There are mobile phone antennas that become involved in the construction of outposts; there are roofing details that function politically. I try to discuss military technologies that contributed to strategic change. I would say that my approach would be to always start with a ferocious and detailed examination of material reality as an attempt to unfold larger force fields and networks of relations that are folded into it.

I think that there are some ways in which what I call architecture — the organization of matter across space — could be seen as a sensor to those forces that shaped it. Space is a political plastic, in the sense that its materiality is continuously shaped and reshaped by those political forces. At the same time, I would also add that the way that political force is folded into material form is never linear, mechanical, and direct.

Architecture should thus better be seen as a weak sensor. It’s not as calibrated as a mercury-in-glass thermometer in that its relation to the phenomena is not linear. So it’s a kind of sensor that we need to be very attuned to in order to understand, to read, to interpret, to debate, and to weave what I hope will be ever more complicated networks of practices and their interaction with materiality. This process of interpretation and debate is based on the weakness of architecture as a sensor: forensic architecture needs the forum precisely because its findings are ambiguous.

Schapira: One issue you discuss in The Least of All Possible Evils is attaching a different significance to forensics, looking at the term in light of its shared entomological inheritance with the forum, which is a place of debate and the site of legal decisions where evidence would be put forward. There is now an aesthetic dimension to this — the image has emerged with a new force as a form of persuasion. I’m wondering if you can speak more to your reading of forensics, and perhaps link it with the recent work you’ve done on forensic aesthetics.

Yes, I divide the work on forensics to “fields” and “forums.” Forensic Architecture is grounded in both field-work and forum-work; fields are the sites of investigation and analysis and forums the political spaces in which analysis is presented and contested. Each of theses sites presents a host of architectural and political problems.

In fields, lets say starting with Territories, I attempted to engage a kind of “archeology” of present conditions as they could be read, or misread, in architecture. This archeology is not always undertaken by direct contact with the materiality under analysis, but with images of it. The spaces that we debate, analyze, or make claims on behalf of, are very often media products. Similarly, drawing a map includes synthesizing satellite and aerial images as well as images from the ground. Some images are created by optics and some by different sensors that register spectrums beyond the visible. One needs sensors to read sensors.

So this is a kind of archaeology of spaces as they are captured in these different forms of capture and registration. You read details, speckles, pixels and patterns, connect them to larger forces, or at least you understand the impossibility of doing so, often noting paradoxes and misrepresentations. We have done this very close reading of aerial images of colonies in the West Bank, we have read almost all elements from architectural through infrastructural archaeological to horticultural ones visible in these images as a set of tools in a battlefield.

Then there is the forum: a site of interpretation, verification, argumentation and decision. International courtrooms, tribunals, and human rights councils are of course the most obvious sites of contemporary forensics. But there are other political and professional forums.

Each forum is different. The third component of forensics, beyond the architectural and aesthetic, is what you need in order to stand between that “thing” and the forum: an “interpreter.” In ancient Rome it would be the orator; in our days it is perhaps the scientist, or the architect, or the geographer — the “expert witness” that translates from the language of space to the language of the forum. This definition of forensics might help expand the meaning of the term from the legal context to all sorts of others. Politics, as it is undertaken, around the problems of space and its interpretations, is a “forensic politics” as far I understand it.

Each of the multiple political and legal forums in use today — professional, scientific, parliamentary or legal — operates by a different set of protocols of representation and debate. They each have another frame of analysis. Each embodies dominant political forces and ideologies — that is to say that each instrumentalizes forensics as a part of a different ideological structure. In the turbulence of a changing world, there are also informal, subversive and ad-hoc and crisis forms of gathering: pop-up assemblies of protest and revolt in which the debate of financial, architectural (the housing or mortgage crisis), and geopolitical issues are often articulated.

Forensic architecture should thus be understood not only as dealing with the interpretation of past events as they register in spatial products, but about the construction of new forums. It is both an act of claim-making on the bases of spatial research and potentially an act of forum-building.

Carla Hung: This interplay between subjectivity and objectivity has become increasingly important in your work. In The Least of All Possible Evils there is a moment when the Israeli Wall is being put on trial and not its architects. So the object is demanding a subjective responsibility to interpret it in different ways. Is there a displacement of the subjective person as witness when we start focusing on objects, and is there also something to be gained by the truth finding of an objective witness compared to a subjective one?

Here I should return to the other part of your previous question about “forensic aesthetics” to lead onto the very important point you raise. Forensic aesthetics, something that Tom Keenan and I developed in our work on Mengele’s Skull is linked to the notion of decision.

Decision is important in a forensic process because it needs to determine a debate that can never be conclusive, that is always a matter of the balance of probability. Just like in a legal case where “beyond a reasonable doubt” or other measures of probability await a decision or conviction — a term that combined a guilty verdict with a sense of constructed belief. Different fields — science, law, and politics — have different mechanisms for making decisions and checking them.

Forensic aesthetics is in our opinion the way in which the presentation of a case, by all sorts of techniques of presentation, gesture and theatrics, allows a particular fact to be made and then a decision to be undertaken. Decisions may be partially based on the aesthetics of evidence, in the sense of the way that things appear, but they imply responsibility because the decision is followed by an action with consequences.

But now the question is what kind of evidence we are talking about, and here your question about human or non-human, subjective or objective is important. We looked at an aspect of the history of trials of international humanitarian law, the laws of war, which sometimes intersects with the history of criminal law and the techniques and technologies of forensic science, policing work, and testimony in its service, but also has its unique genealogy.

In our opinion, very broadly speaking but somehow usefully, you can divide the history of international law trials into periods in which different types of evidence were in the foreground. In most legal codes, evidence is divided into: documentary, testimonial, and physical. Although, of course, in all cases we observed complex entanglements between these, at different times, a different form of evidence is being most structural to our understanding of the event in question, with aesthetic, political, and ethical consequences.

For example, in the immediate aftermath of WWII Robert Jackson prosecuted the Nuremberg trial mostly on the basis of documents. Having just gained an enormous trophy of millions of documents, he engaged in a certain archival frenzy and tried to base his prosecution strategy on the words of the German leadership as written in the documents that circulated through the Nazi state’s nervous system.

There was a fear in involving the survivors themselves, who were still seen as barely partners for a professional legal process. There were a lot of displaced people in Germany, survivors, whom he could have spoken to, but they were seen as unreliable at best, barely humans at worst. The trial focused on the mechanism of government, decision making — in a sense of what can be seen in it and learnt from it — it concentrated on the people at the top and their responsibility for state actions.

In the 1961 Eichmann trial, the first transformation occurred where those witnesses who were more or less banned from Nuremberg were taking center stage. As Arendt correctly objects, most have not directly met Eichmann. But there was a political attempt by the Israeli state to enact a kind of national and international pedagogy. This introduces the victim for the first time and therefore starts what scholars call the “era of testimony” or the “era of the victim.” The methodologies of humanitarianism and human rights were enormously influenced by this introduction of the victim/witness into the methodologies and epistemologies of international law.

Testimony started appearing not only as an epistemic frame to learn about things and situations, but also as an ethical, political, and aesthetical one. To take the side of the oppressed, history was more receptive to aural traditions, etc. Human rights groups adopted testimonies of individuals as their main methodology. And through testimony they demonstrated their support of liberal values of free speech in taking the side of individuals against repressive “totalitarian states” as the socialist eastern bloc started being referred to. Humanitarian groups like MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières) politicize themselves by adding témoignage to medical aid starting in the early 1970s. Testimony reframed the way in which we saw and understood the world in front of us: a world of victims.

The current shift in emphasis to science, to image analysis, to materiality, to space is not new: since the industrial and scientific revolution of the mid-19th century, physical evidence has gradually become more important. But it hasn’t had such a large effect on human rights and international law until recently. Something important has shifted with the self-proclaimed scientific ability to see more and more data in the physical world, a virtual explosion of information. Expert witnesses emerge in HR contexts, ex soldiers testify about the effect of weapons and ammunitions, pathologists replace interviewers, etc. Although of course testimony is still going strong, the entire aesthetic field — what is visible, what counts, what is important to look at, what can be seen, what we put our attention to — has shifted with this shift in sensibility and new relationships are formed between testimony and evidence.

This is something that is increasingly reflected or echoed in popular entertainment. If the psychologist as detective was the embodiment of the psychologizing era of the witness, the forensic detective is the popular hero of our time of material investigation.

Hung: If the current drive to materiality and forensic analysis has penetrated law, humanitarianism, and even aspects of popular entertainment, has something similar occurred in the news media as well?

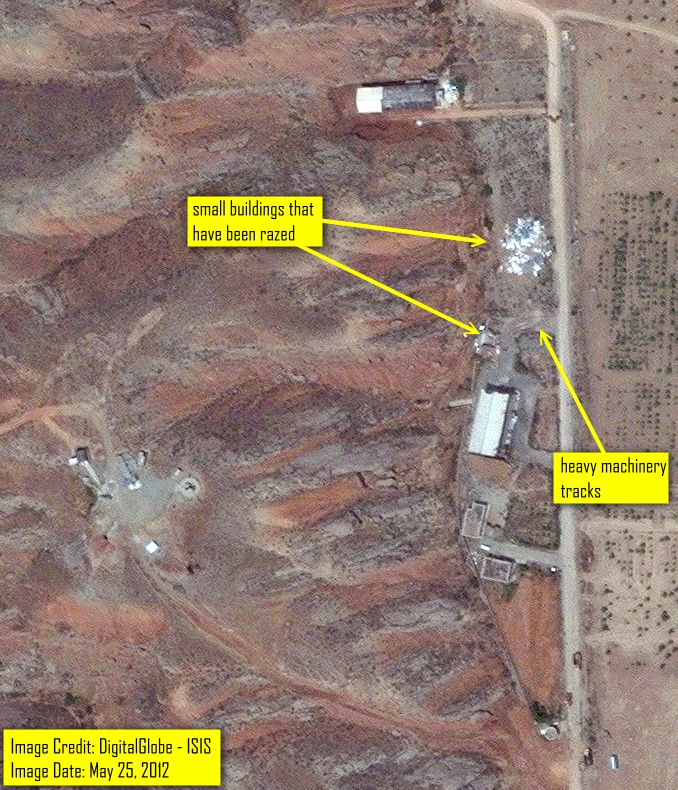

Very often you can see on the front or on the second page of the New York Times satellite images of some “suspected nuclear facilities” in Iran, say.

But we can also see the spread of on-the-ground videos shot on cell phones. The remote imagining of satellite imagery, captured at a higher altitude than the vertical extension of state sovereignty (national air-space is cupped by the lowest possible orbit a satellite can travel upon) now intersects with video activism, filmed and uploaded at close range at the risk of their makers. In a recent lecture, Rabih Mroué showed footage from cameras of people being killed while holding the cameras. For the people filming at the risk of their death this is obviously a heroic act of truth-telling, but the technologies and cycles of their availability allow these images to circulate and respond also to a host of other interests.

So the entangled, or almost simultaneous emergence, of these two very different forms of media demonstrates the growing appetite of many international organizations to arbitrate on situations unfolding in areas hard or impossible for them to access. These technologies allow alternative political groups, advocates of human rights and also policy-makers to circumvent state restrictions on data circulation. Their intersection also transforms the way we interpret the consequences of violence and experience the sufferings of people far away from us.

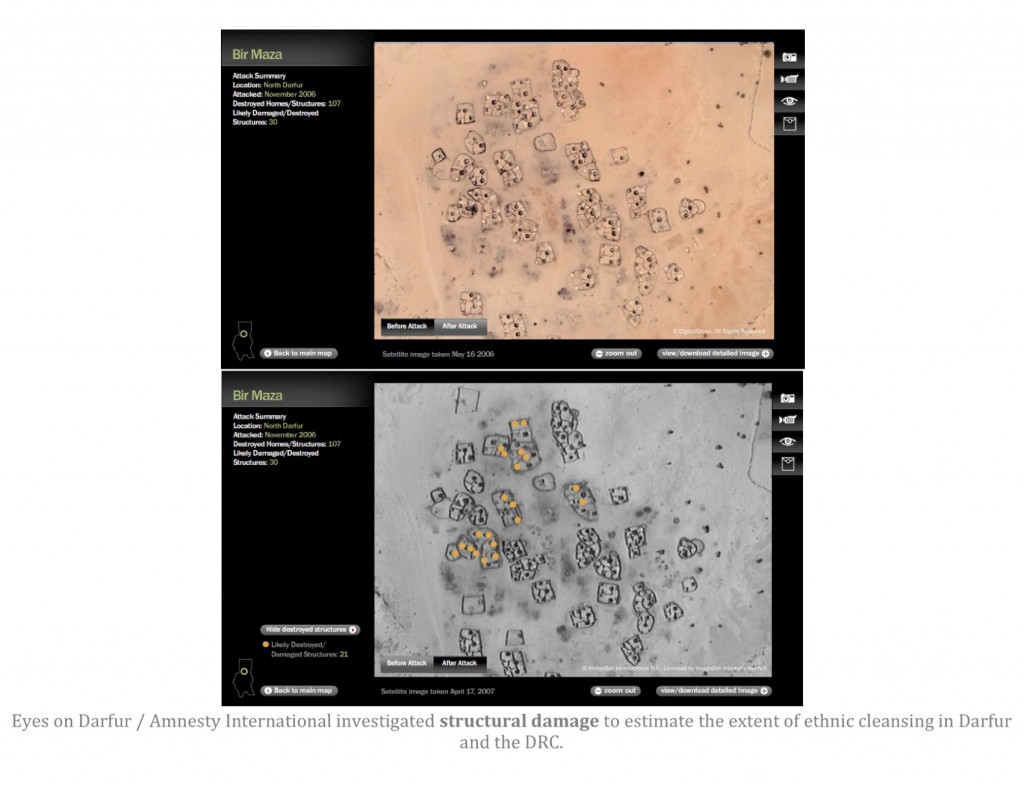

When crisis occurs, or is expected to occur, state, UN, or commercially operated satellites (the latter hope to sell their images to states or private organizations) start photographing “regions of interest” around “areas in risk” in higher frequency and at higher resolution. Because there is a time lag between runs, the act of violence or destruction is often missed. This is the reason that satellite imagery is often presented in “before and after” sequences. To a great extent before and after images are the very embodiment of an emergent “forensic time.” While activists’ videos capture the event itself, the stereoscopic montage of before and after leaves a lacuna at the heart of the event.

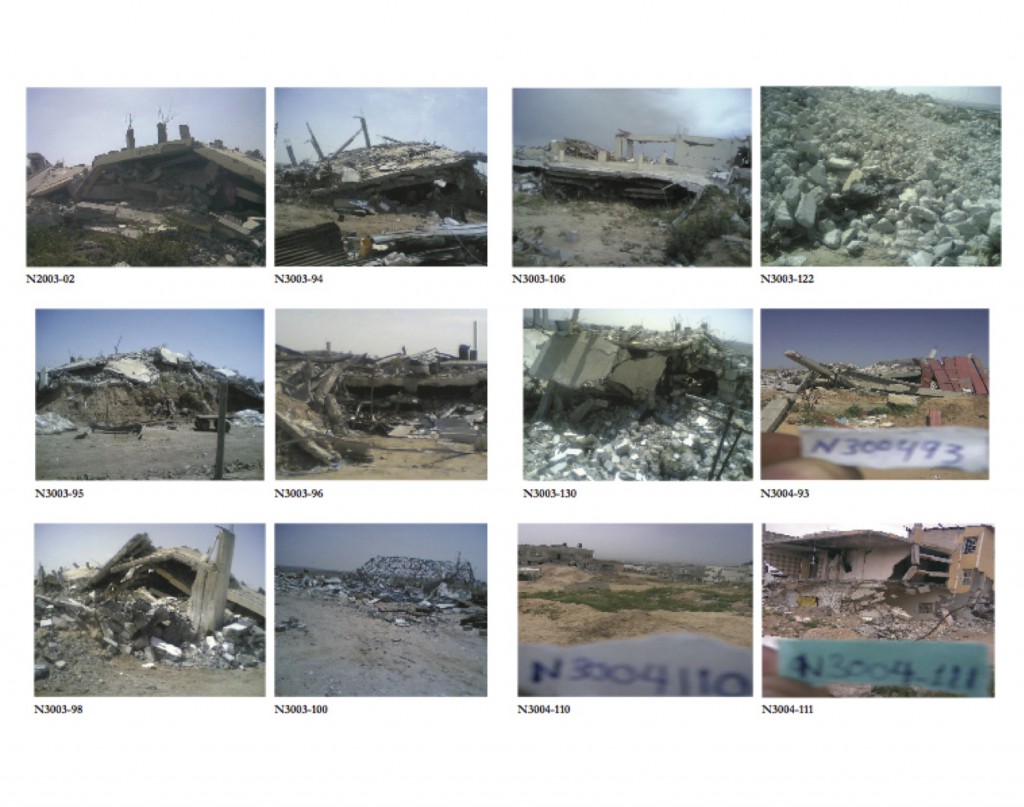

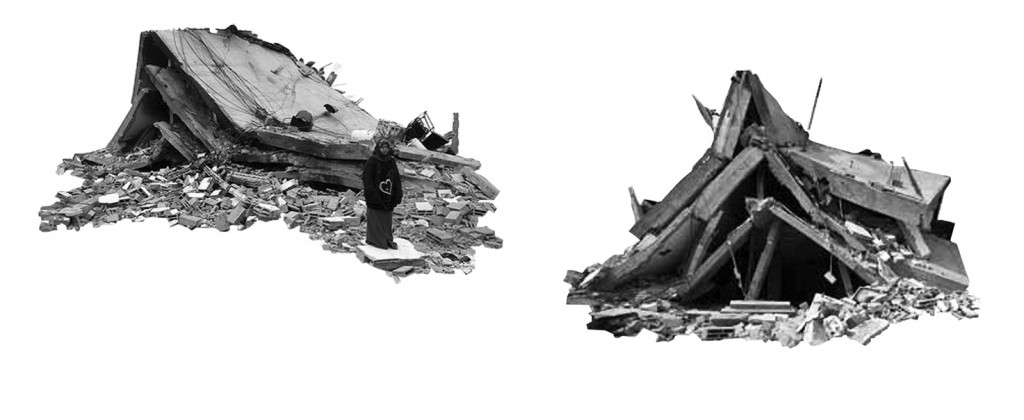

In these forms of media, the built environment is seen as the depository of political events. But can we read and interpret events from images of trash and rubble? Does a freshly dug out earth mound in eastern Iran signify — as claims made in its name — the construction of a new subterranean bunker in which banned weapons are produced? Could we directly connect earthworks and nuclear process? Does a similar earth mound now captured by satellites orbiting over Libya, Syria, Darfur or Sri Lanka signify sites of mass inhumation in common graves? Was a destroyed building, visible in an “after” photograph, destroyed by people from the ground, or by their enemies in an aerial attack? Can satellite-mounted radars, heat sensors, and thermal imaging, capable of registering wavelengths beyond the visual spectrum, detect the fractional temperature variations of changing vegetation patterns in previously cultivated fields, now falling foul in absence of their farmers? Can genocide, ethnic cleaning and other crimes against humanity be indeed confirmed by visualizing the invisible ranges of the spectrum?

Now there is a lot of testimony from Darfur, but this is not what we want to hear. We want to see the evidence. I think the implication of this is that there is a certain silencing of testimony; it’s overpowered by evidence. Another example can be seen in Gaza when the Goldstone report shifts its methodological balance from testimony to physical evidence like pathology, weapons studies, and forensic architecture performed on damaged buildings. What they are saying in fact is that we cannot listen to or believe testimony in Gaza from the Palestinians — because they are politically manipulated by Hamas. ….

So very often we have situations where testimony is not mobilized in a way that it should be, as a kind of intertwined assemblage of conversation between the material and immaterial, between human and non-human, between the subject and the object. Rather the object starts taking the place of the subject, and when it takes it a lot of other things happen.

Schapira: You see another aspect of this right at the beginning of The Least of All Possible Evils. There is photograph of a man explaining a complicated equation on a white board, and we learn that this equation is meant to mathematically demonstrate how Hamas can be dismantled by killing key operatives. This adoption of a supposedly more scientific or objective point of view is meant to render judgment and tactics more reliable. I’m wondering if perhaps this new moment in humanitarianism and the prosecution of war that operates under these forms of calculations has more of an effect on the practice of these interventions, or how we understand them?

In a shift to materiality the object can emerge always and only as an object of calculation. These are questions of numbers, and questions of numbers operate in relation to thresholds. Does the death and destruction caused in Gaza amount to war crimes? To violations of human rights? To crimes against humanity? Technically these are not only quantitative but qualitative questions, but they are influenced by figures.

War itself becomes increasingly a matter of calculations the more computered and “smart” the military hardware becomes. Violence is of course unpredictable but, allergic to indeterminacy as militaries are, there are ongoing attempts to harness this chaos into calculations. The next stage after that of smart weapons was the development of techniques of damage calculation — how much destruction targeted explosions might cause. It is an “art form” that combines blast dynamics with structural engineering. There is software — today it’s called Fast Collateral Damage (FAST-CD), before it was called “Bugsplat”, this horrible title — for calculating civilian casualties.

Once militaries can present themselves with estimates regarding the number of casualties — although these could be widely wrong — they have to make decisions in relation to this predicted number. Legally — and militaries have to increasingly operate in a legal environment — they have to justify this level of death by conjuring an economy that is organized around the legal principle of proportionality. In the beginning of the Iraq War the proportionality calculations of the Pentagon allowed the killing of up to 29 civilians for every political/military leader.

I think that this teaches us two things about the contemporary use of humanitarian principles. One is on the level of justification. We know in the context of the Libya intervention that there were geopolitical, economic, and migratory interests of European states to change the regime, and they tried to give the war a humanitarian justification. The other level is that humanitarian law enters the logic of the very organization of violence — how violence is structured, dispensed, distributed, etc. Both aspects must be avoided at all cost!

Schapira: This is a more general question, I guess again about method, but more particularly about your use of theory. Some people will dismiss high theory as being inapplicable to experience or an over-jargonized form of academic discourse. Yet by looking at the training of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) you show how some of these theoretical insights find uptake in very concrete military strategies — e.g. inverting urban space by moving within buildings as opposed to in the streets. Do you think that even if people are dismissive of certain theorists, they are nonetheless marking something like a saturation of thought that eventually does find its way into practice? For example, you just mentioned the use of smart technology in things like drone strikes. Might this have to do with issues of territoriality, or people talking about the decline of sovereignty in the nation-state?

I think that there is a kind of co-evolution between the production of concepts — if this is what philosophy is after Deleuze — and practical experience on the level of politics, the military, or the level of resistance. Concepts are most often produced as an entanglement of practice and thinking. The case of OTRI (Operational Theory Research Institute) that I wrote about in Hollow Land is almost a caricature of the way in which some very basic readings of Deleuze structured forms of maneuver. But more than that they function as the introduction of a new language into the IDF that is aimed to change hierarchies of command within it.

Today the frontier is elsewhere: new optical and imaging technologies, new modes of analysis and interpretation, give rise to new political concepts. I think that’s a part of the forensic imagination. New imaging technologies connect to the geopolitics of state borders, both by state agents and their militaries and by civil society trying to reclaim these tools itself. It is between those scales — geopolitics and image production — that I see my work operating, both as a critique and as a form of involvement in that field of the production of images in relation to conflicts.

This post may contain affiliate links.