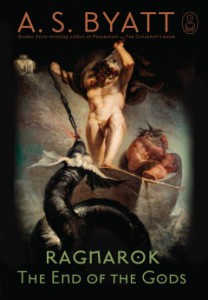

Ragnarök: The End of the Gods is A.S. Byatt’s contribution to the Canongate Myths series, a collection that includes retellings by Margaret Atwood, Jeanette Winterson, Philip Pullman, and others. Byatt’s book takes up the Norse myths which have always fascinated her, and which have appeared briefly in some of her previous fiction as a topic of fascination for her characters. Here she brings them to her readers through a nameless main character, “the thin child,” who reads about them during WWII in England (the setting, like the thin child, is only barely sketched out). Ragnarök is also a war story — one in which, as the title suggests, nothing survives.

The narrative moves between the thin child’s solitary world, in which she reads and speculates, and the bright, savage world of the gods she reads about. The juxtaposition of worlds lets the child draw conclusions about war and belief: “She thought long and hard, as she walked, about the meaning of belief. She did not believe the stories in Asgard and the Gods. But they were coiled like smoke in her skull, humming like dark bees in a hive.” It is not hard to conclude that the thin child is Byatt’s youthful avatar, a character who reads mythology voraciously and learns to reject the aesthetics and logic of the Christian narrative of redemption. This conclusion is supported by the rather unexciting, demystifying commentary that follows the story (these things are better left to interviews, so the reader doesn’t feel obligated to read them).

Remarkably, and happily, Byatt manages to fill even this little book with her characteristic dense, glossy prose, each page carefully embroidered with beautifully knotted images. The intensity of sound and image work well in Ragnarök. The gods’ stories are told without any attempt at giving them emotional depth; similarly, the thin child’s story resists descriptions of childlike feeling and confusion, mentioning with little commentary, for example, that the child expects never to see her father return from war. Oblique parallels between the war of the thin child’s reality and the war of the gods she is reading resonate more deeply than would any direct comment. Resistances to empathetic depth here are replaced by a rich, communicative evocation of atmosphere and a wild reveling in language:

Not far from Rándrasill underwater craters spouted crimson and scarlet pumice and thick black smoke. But here, everything was as it was, everything was abundant. Sponges, anemones, worms, crayfish, snails of every colour, ruby, chalky, jet, butter-yellow, sea slugs magnificently striped and mottled, supping up jelly from the fronds. Abalone were anchored round the holdfast, throngs of the shells in pink, red, green and the most succulent white. Sea urchins, bristling with fine live spines, grazed the thick algae and hundreds of eyes peered out between the sheltering fronds of the great plant as it swayed in the slow currents. Elvers moved like needles through cushions of sargasso. Jörmungandr, lying limp, and staring with delight, picked out the sargasso fish, trailing coloured flags of flesh indistinguishable from the weeds, by its watchful eye, like a pinhead amongst the growths.

Ragnarök does not move forward very quickly, but it does not lack dynamism; its energy is located in the teeming, swirling descriptions. This trait did necessitate, at first, a kind of chain-stitch reading pattern, constantly looping back through the story to progress a little farther. This is not to complain, only to say, this story makes you rise to the challenge of its language. That rise, as the thin child knows, is what makes reading so fiercely joyful.

This post may contain affiliate links.