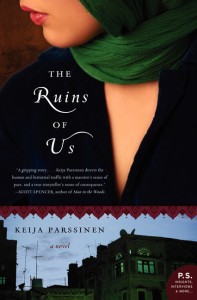

Set against the dramatic and often maddening backdrop of Saudi Arabia — a land of opulence and opportunity, frustrations and limitations — The Ruins of Us is epic, tragic, and sometimes overwrought. This first novel by Keija Parssinen is a purposeful introduction for Western readers to the complicated terrain of Saudi society that grapples with religious extremism and polygamy amid the dangerous allure of the desert. Despite the occasional swerve towards melodrama, Parssinen accomplishes her difficult task through an honest and emotionally resonant narrative.

The Ruins of Us centers on an American woman, Rosalie, who married a Saudi man, Abdullah, when they were both attending university in Texas, and moved with him back to Saudi Arabia where Abdullah became a millionaire tycoon. Once the couple has seen their two children grow into their teens and the sheen of their romance begin to dull, Abdullah decides to take a second wife in secret. Rosalie only finds out by chance, after her husband has been married to the other woman for two years, and she is understandably upset. The plot takes many turns as Faisal, Abdullah and Rosalie’s son, becomes involved with the fate of a dissident Sheikh, and as Rosalie has an almost-romance with Abdullah’s sad-sack best friend, fellow Texan Dan.

The book is a frustrating read, and it is hard to tell whether that frustration comes out of the limitations of Parssinen’s narrative, or the actual limitations of life in Saudi Arabia.

There are certain sentiments that ring hollow. Marriage, for example, is lifted up as the greatest possible expression of love, an idea that seems a little simplistic and silly, particularly in the context of a culture where men and women stand on such unequal footing. Reflecting on and attempting to justify Abdullah’s taking of a second wife, the American Dan thinks to himself:

Wasn’t marriage the ultimate expression of that vaunted emotion, that truest love? And if one should be lucky enough to feel love twice in one lifetime, well, why not?

And Rosalie eventually decides to stay with her husband despite his hubristic betrayal because, as she says:

“That bastard is the love of my life. My happiness is bound up in him. I’d rather have this compromised life with him than be alone up on my moral high ground…he’s a good man, Dan. You know that.”

But throughout most of the book, it is hard to find Abdullah to be a good man. He is wealthy and powerful and seems perfectly content marginalizing a woman who has actually given up every freedom to be with him: the freedom to drive, to wear jeans, to be alone in a room with a man other than her husband, her son, or her father. And she has given up the freedom to divorce and maintain custody of her children.

But at the same time as Parssinen builds up this dramatically unequal relationship as a great and epic love, she is also insightful in picking out exactly what is so painful about being a woman in Rosalie’s position: “Plenty of neighbors screwed around with each other in the states, but there was something infinitely kinder in a culture that recognized such behavior as shameful.”

The relationship between Rosalie and Abdullah ultimately rings true because the novel ends with all of its earlier assumptions deep in doubt. Rosalie is not angry anymore, but Abdullah is not forgiven. The second wife is still around, but Abdullah is no longer comfortable in his self-justifications. Faisal, the son, ultimately chooses his compromised family over ideological purity, but the choice is not easy. Though the novel ends with a kind of grand reconciliation, that reconciliation does not yield a happy family or the resolution to any conflict.

Parssinen works through these complex dynamics with such insight in part because she is writing from experience. An American, Parssinen spent the first twelve years of her life growing up on a compound in Saudi Arabia before her family moved to Texas — the mirror image of what Rosalie does in the book. Parssinen writes from the perspective of an intimate outsider who presumably can sympathize with the strange, nostalgic pull that Saudi Arabia held for Rosalie before she decided to build a life there.

Faisal asks his mother at one point:

“Why did you come here?…Didn’t you know? Didn’t Baba tell you what it would be like?”

And Rosalie questions her own wisdom in accepting the life she has led:

She wondered if she could be called smart. Since she was twenty, she’d allowed herself to be led by the hand.

The Ruins of Us is a novel about place written for people who are not from that place. While reading it, I was constantly frustrated with the way both Rosalie and Abdullah play by the rules of Saudi society. But that very conflict that I felt as a reader is the accomplishment of Parssinen’s book. In describing this family, half American and half Saudi, Parssinen forces readers to accept and understand Saudi Arabia to some degree, and, like the characters in the novel, to face and begin to overcome their own discomfort with the country — but not without questions.

This post may contain affiliate links.