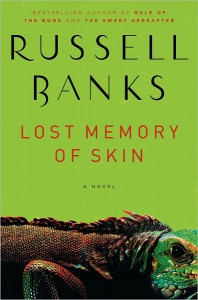

There are plenty of things worth discussing about Russell Banks’ latest novel, Lost Memory of Skin (the erosion of sexual and emotional intimacy in the internet age, the repercussions of living duplicitous lives, the causes and consequences of personal vices, obsessions, and addictions), but the most pertinent to mention right off the bat is this: its 22-year-old virginal protagonist, the Kid, is a convicted sex offender. He lives among former boxers and senators charged with sex crimes beneath a south Florida causeway, one of few places 2,500 feet away from areas where children gather. Cooped up at night in a small sleeping bag and tent, the Kid spends his days bussing at a local restaurant, eating meager meals of junk food and beer, and caring for his beloved pet iguana, Iggy.

There are plenty of things worth discussing about Russell Banks’ latest novel, Lost Memory of Skin (the erosion of sexual and emotional intimacy in the internet age, the repercussions of living duplicitous lives, the causes and consequences of personal vices, obsessions, and addictions), but the most pertinent to mention right off the bat is this: its 22-year-old virginal protagonist, the Kid, is a convicted sex offender. He lives among former boxers and senators charged with sex crimes beneath a south Florida causeway, one of few places 2,500 feet away from areas where children gather. Cooped up at night in a small sleeping bag and tent, the Kid spends his days bussing at a local restaurant, eating meager meals of junk food and beer, and caring for his beloved pet iguana, Iggy.

Banks deserves acclaim for dropping readers into dark terrain that few authors traverse, but such praise runs the risk of overlooking the craftsmanship he pours into shaping a sympathetic character, not merely a sympathetic sex offender. The first quarter of Lost Memory of Skin remarkably balances characterizing the Kid independently of his conviction (at work he “likes wearing the starched white jacket with the mandarin collar. It makes him feel like he’s a scientist.”) and casting the Kid’s observations in the shadow of his past and present afflictions (after reading Genesis, he “wonders if it’s possible that this whole tree of knowledge of good and evil thing was set up by God as a kind of prehistoric sex-sting.”).

Banks not only earns reader sympathy for the Kid by laying necessary character groundwork, but also by simultaneously inverting and blurring the roles of culprit and victim. When police raid the causeway, nearby reporters look on “like they’re customers at a sex show who don’t want you to know it’s turning them on.” During his brief training stint in the Army, the Kid’s fellow soldiers strip him in the shower and mock his large penis for being wasted on a virgin. The Kid’s mother, after discovering him watching porn, scolds her son before staying to watch an onscreen gangbang “as if it was a Ninja video game.” Through his supporting cast, Banks suggests that most individuals are not unlike the Kid–-burdened by compromised morals, predatory and voyeuristic instincts aroused by barrages of sexual images. Only his decision to visit a 14-year-old girl with a six-pack and a porn DVD separates the Kid from life beyond the causeway.

The novel works best when Banks teases his aforementioned themes out of the Kid’s solitary routine. Simple thoughts coursing through the Kid’s head (of a suburban home: “He wasn’t aware that comfy good-looking rooms like this even existed except in magazine ads and on TV. It’s more like a set for actors to use for an upscale porn film than a real home for real people.”) evoke deeper reader contemplation than expository dialogue or narrative momentum ever could. Banks feels obligated, however, to overcome the Kid’s solitude and emotional disconnect by presenting him with a foil, or, as Banks subtly frames it in the book and more overtly in interview, a Long John Silver to his Jim Hawkins.

Into the narrative waddles the Professor, a renowned local genius and rotund, food addicted sociologist. Convinced that sexual offense stems from loss of personal power rather than perversion, the Professor helps the causeway occupants erect an organizational structure to prove to the outside world that they can exist civilly in their sequestered space if given responsibility and clout. The Professor depends on the Kid to launch his experiment and, providing food and shelter funds in exchange, begins interviewing him.

“The Kid doesn’t want to talk about the Professor,” Banks writes halfway into the book. “He takes up too much space, uses too many words, has too many theories and ideas. The Kid doesn’t want the Professor’s ideas and plans and his size to become his, the Kid’s.” It’s a valid concern that Banks never successfully circumvents. The Professor’s food dependency and shady history provide some intriguing echoes and contrasts to the Kid’s porn-tainted past, but the comparative opportunity also forces Banks’ themes to the novel’s surface in imposing, unsatisfying ways. The Professor is less a realized character than a politicizing bullhorn. Though he raises reasoned points, he illuminates nothing as compellingly as the Kid’s story does, and with far less pontificating to boot. “It’s like all of America has turned into a cop whose main job is to protect their fourteen-year-old virgins from creeps like me,” the Kid moans to the Professor during a later interview. The Professor’s theories and ideas have finally started displacing the Kid’s–-the Kid never would have uttered this kind of overwritten proclamation before encountering the Professor.

Lost Memory of Skin ultimately fails to settle on a plot deserving of its protagonist. The Kid remains so stirring, however, so authentic throughout, that one can forgive the mismatched pairing. And while Banks’ plotting never quite clicks, his humor elevates the writing out of the relentlessly dark dirge it could so easily have slipped into in lesser hands. Banks couldn’t make it through a 2010 reading without cracking up. It’s another surprising thing, like the Kid, to which readers will relate.

This post may contain affiliate links.