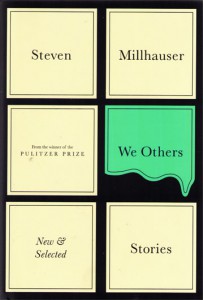

[Knopf; 2011]

The new stories in Steven Millhauser’s We Others: New and Selected Stories uphold Millhauser’s reputation as a literary fabulist concerned with the strange depths of the seemingly ordinary. At their most compelling, these recent stories address Millhauser’s preoccupation with the intersection between expectation and disappointment, sensuality and revulsion.

The earlier stories selected for We Others are taken from In the Penny Arcade (1981), The Barnum Museum (1990), The Knife Thrower (1998), and Dangerous Laughter (2008). Throughout his career, Millhauser has pursued fiction with unusual and divergent subject matter, from a winter landscape overrun with self-replicating snowmen (“Snowmen”) to a businessman overwhelmed by words, who takes a vow of silence to the consternation of his wife (“History of a Disturbance”).

A surfeit of unusual circumstances does not in itself prove an abundance of imagination, or certify that the phantasms are meaningfully evoked. What makes fiction spellbinding is its ability to embody the language of lived experience with depth and range. The strongest stories of Millhauser’s oeuvre take time to unfold, even as they open with fantastic premises. This is true of the patient inventory of the labyrinthine, impossible exhibition rooms of “The Barnum Museum” and of the descriptions of the intricate craftsmanship of the title character in “August Eschenburg,” who creates lifelike figures in miniature that move with the mechanisms of a clock. “Eisenheim the Illusionist” and the “The Knife Thrower” are stories that traffic in smoke and mirrors and crystal balls, but are ultimately sophisticated explorations of the nature of perception and of fiction-making.

In contrast, several of the new stories in We Others feel rote and concept-driven in their execution: quirky or disturbing circumstances becoming a shorthand for inventiveness. “The Next Thing,” about a menacing subterranean shopping center, takes all the expected plot turns as the corporate behemoth’s conquest progresses on the unsuspecting town. “People of the Book” apes a biblical tone with none of Scripture’s richness and complexity.

After many restrained, psychologically astute passages, the ending to “Tales of Darkness and the Unknown, Vol. XIV: The White Glove” is appallingly literal. I couldn’t tell whether the story was taking itself far too seriously or was suddenly afraid to take itself seriously, content to fall back on the same arch tone of its title. The title story of We Others follows a ghost haunted by his own obsession with two lonely women he visits. This supernatural story is obstructed by redundant explications that halt suspense and extend the story unnecessarily to near-novella length.

New stories such as “We Others” and “The Slap” are told predominately in the first person plural, embodying the fallible omniscience of the crowd. This is used to great effect in “The Slap,” the opening story of the collection. An affluent suburb is besieged by an unidentified assailant who slaps citizens without a recognizable motive. After the attacker disappears, his calculated violence still unexplained, the “We” of the story are able to relax, but simultaneously develop “an odd kind of envy, as if, by not being slapped, we had failed to be part of a profound moment, had somehow, by our caution, evaded a call to adventure.”

Comparable in enchantment to “Eisenheim the Illusionist” and “The Knife Thrower” is Millhauser’s attention to the handmade magic of childhood, another theme that surfaces across the stories collected in We Others. “Flying Carpets” brings the two worlds together with a flawless nonchalance. It begins:

In the long summers of my childhood, games flared up suddenly, burned to a brightness, and vanished forever. The summers were so long that they gradually grew longer than the whole year, they stretched out slowly beyond the edges of our lives, but at every moment of their vastness they were drawing to an end, for that’s what summers mostly did: they taunted us with endings, marched always into the long shadow thrown backward by the end of vacation.

From the outset of “Flying Carpets,” the distinction between literal and figurative is irrelevant, because the seamless mingling of the two is what most accurately conveys the experience of childhood. Millhauser has a wonderful sense of the precocious child’s inner life, even if all his young protagonists are squeamish, severe, and overly articulate. The philosophical young boy in the new story “Getting Closer” thrums with life. The premise of this short work of fiction is simple. There is no suburban-supernatural, and no fin-de-siècle dark magic. Straightforward and irrefutable, a boy jumps into a river—with something like simplicity, and with something like the burden of his whole life. Now that’s the magic of fiction at work.

This post may contain affiliate links.