My least favorite form of journalism is the “twitter reaction piece” and my second least favorite form of journalism is the trend piece – but my most favorite book when I was in junior high, Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech, told me that I shouldn’t judge a [wo/]man until I’ve walked two moons in his[/her] moccasins, so I’ll give the “trend piece” a try:

I’ve noticed a trend today of trend pieces (trends about trends!) about the types of fiction people are writing in this, our modern, depressed economy, ebook world.

On Tuesday, Salon’s Jeff Martin wrote an author round-up style piece about a “new literary movement” of “socioeconomic realists,” born of the economic devastation of the past three years that, along with olds and people of color, has hit the youngest sector of the job market particularly hard.

The theory behind this trend piece – all trend pieces have a theory – is that bad economic times have created a wave of Great Realist Literature. Martin writes:

While no one would ever wish for high unemployment or a schizophrenic stock market, it’s always brought out the best in our writers.

I didn’t read the version of the article that accidentally, according to Salon, included “research material culled from other sources – and not intended for publication” but the article as it is doesn’t do enough for me to capture the feeling of the books covered. Perhaps Martin hasn’t read all the titles he’s writing about, perhaps he has. Either way, using words like “gritty” and author comparisons like “the bastard children of Jim Harrison and Raymond Carver” and “echos of John Steinbeck” do about as much for me as a marketing blurb.*

The books and the undoubtedly talented authors covered might all have something in common, they might all capture something essential about the America we are currently living in, but the nature of the trend piece is to force everything to fit the same single-sentence description. A more interesting piece might’ve pivoted into “socioeconomic realists” (possibly fake) trend by focusing more on Bonnie Jo Campbell, whose “gritty” early novels failed to connect but post-Great Recession novel American Salvage found a larger, more enthusiastic audience.

Late last week, the excellent lit website The Millions published a trend piece by Kim Wright, mostly about writers who used to write “literary” fiction transition into writing genre fiction, mixing genre tropes with styles they consider traditionally part of the literary canon (though, I would argue, that is a problematic stance). As an offshoot of this trend, Wright stumbles upon the same theory Martin did, that the bad market might produce Great Literature, but with a different impetus:

In other words, this crappy market may actually end up producing better books. Because hybrids, bastards, and half-breeds tend to be heartier than those delicate offspring that result from too much careful inbreeding.

Wright’s article has its problems, mostly with the interviewees whose ideas are too muddled and, unfortunately, not corralled into some kind of coherence. I like that Wright chose to interview publicists as well as writers, but I don’t like the way that the ease of marketing genre fiction seems to butt heads with the unease of some authors writing genre fiction.

One interviewed literary but-now-genre writer, Caroline Leavitt is even quoted as saying “I’ve decided genre is strictly a marketing tool.” She’s wrong, but she means well. Leavitt seems to actually mean that genre fiction isn’t that far off from literary fiction and the border between them is hazy if not artificial and at least partially created in a marketing meeting – if I’m right about Leavitt’s intention, then I agree with her point wholeheartedly. Genre isn’t just a marketing tool – it’s a literary tradition that has thrived longer than the modern construct of “literary” fiction – and when genre is treated as a marketing tool, that tradition is wrongly disregarded.

Despite a few problems, Wright and the (at the time of this writing) not troll-y at all commenters are doing a good job attempting to break down and prove false the hierarchy between genre and “literary” fiction.

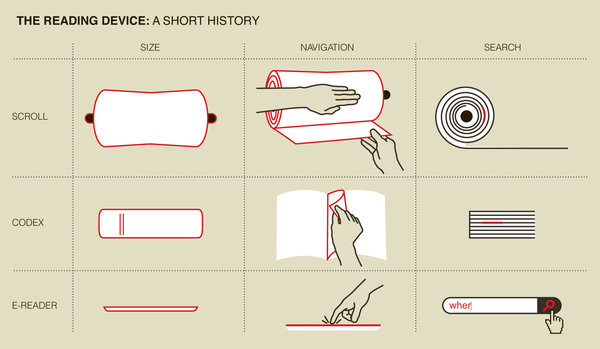

My favorite of last week’s trend pieces is Lev Grossman’s (author of The Magicians and the recently released sequel The Magician King) for The New York Times, basically a fresh take on a new topic: a historical perspective on the (impending?) transition from book to ebook that uses the word “codex” more than once, and equates eReaders to ancient scrolls.

The codex also came with a fringe benefit: It created a very different reading experience. With a codex, for the first time, you could jump to any point in a text instantly, nonlinearly. You could flip back and forth between two pages and even study them both at once. You could cross-check passages and compare them and bookmark them. You could skim if you were bored, and jump back to reread your favorite parts. It was the paper equivalent of random-access memory, and it must have been almost supernaturally empowering. With a scroll you could only trudge through texts the long way, linearly.

But e-books and nonlinearity don’t turn out to be very compatible. Trying to jump from place to place in a long document like a novel is painfully awkward on an e-reader, like trying to play the piano with numb fingers. You either creep through the book incrementally, page by page, or leap wildly from point to point and search term to search term. It’s no wonder that the rise of e-reading has revived two words for classical-era reading technologies: scroll and tablet. That’s the kind of reading you do in an e-book.

Grossman’s piece is a bit luddite for my tastes but it is the only lament about the rise of the ebooks I’ve ever read that captures something more relevant and essential about the shift to digital, rather than just another nostalgic whine about the delight of physical objects.

*(ed. note: It’s perhaps no surprise that Martin’s reads like a marketing blurb — the “material culled from other sources” was, in fact, publicity material for the books Martin was writing about. It’s bad enough that it doesn’t appear that Martin read any of the books he was writing about — the article is full of meaningless, absurd generalizations — but the fact that Salon whitewashed the original piece’s plagiarism and kept it up on the site is insulting. — Alex Shephard)

(image via a trend piece from the New York Times)

This post may contain affiliate links.