by Sam Krowchenko

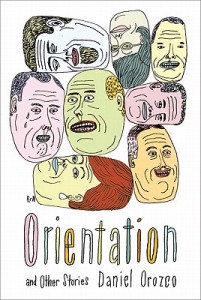

Daniel Orozco’s debut, Orientation: And Other Stories, hangs together by a peculiar, paradoxical thread. To create a cohesive collection about characters perpetually adjusting and readjusting to defamiliarized surroundings and circumstances, Orozco’s technique and tone sporadically changes from story to story. The only route to thematic harmony, it seems, is technical and tonal disharmony. Since his oft-anthologized titular story (a second-person parody of orientation at a drab, cubicle-cluttered office) first ran in The Seattle Review in 1994, Orozco has consistently shed stylistic skins for radically different narrative approaches. Such departures have generated an ambitious body of work, yet Orientation frequently feels like its myriad modes and methods serve banal sentiment rather than substantive storytelling.

“Officers Weep,” represents Orozco at his most mirthful and mawkish. Written in the dry, Dragnet-stylings of a police log, the piece chronicles a well-meaning, slightly dim police duo on the daily grind. Early on, the pair investigates a homeowner’s complaint that “the smell of death” lingers around his property. After an odorous mimosa tree is identified as the culprit, Orozco adroitly apes the police report tone while simultaneously characterizing his subjects with his usual perspicacity: “‘The smell of life,’ officer (Shield #647] ponders aloud. Officers nod. Homeowner rolls eyes, nods politely.” As the officers’ emotional arcs become more prominent, however, Orozco drains the story’s drollness and slips into schmaltzy shtick: “Officers watch a ball of sunlight flare up at earth’s edge like a direct hit. Officers assess scene, ascertain world to be beautiful.”

Orientation too often undermines its formal ingenuities and commendable craftsmanship with such moments of heavy-handedness, as if Orozco worries his details don’t speak enough for themselves. The mistress in “Somoza’s Dream,” unaware that her lover, an exiled president, has been assassinated, “sleeps, deep and hard, unencumbered by knowledge or memory or dream. She sleeps like a dead man.” After a father and son in “Hunger Tales” feast on leftovers following the funeral of the former’s wife and the latter’s mother, they “gazed for some time into the corner where the light had gone, cradling and stroking their englobed bellies – their comfort against the gathering dark of a new and alien evening.” In each case, Orozco forces subtle detail into overtness – we can imagine the inevitable hurt of the “unencumbered” mistress without the explicit parallel between her sleep and his death, just as we can discern how the father and son depend on “their englobed bellies” as defenses against tragedy without Orozco identifying “their comfort” for us.

When he relies on those details, however, Orozco compresses complex emotions into precise, powerful moments. In “The Bridge,” Baby, a rookie bridge painter, witnesses a woman fall to her death, and Orozco breaks her jump down into a string of lucid recollections:

“He would remember bleached blue jeans with rips flapping at both knees, and basketball shoes – those red high-tops that kids wear – and the redness of them arcing around, her legs and torso following as she twisted at the hips and straightened out, knifing into the bed of fog below.”

“Only Connect” also explores the repercussions of witnessing death (this time a fatal stick-up), and though Orozco returns to this memory in a similar fashion to “The Bridge,” he also summarizes his character in swift, assured sentences: “She was twenty-nine years old, on the brink of her next decade, and in love with a man who did not call her after she saw somebody die.” Orozco assembles these niceties in a way that doesn’t attempt to regulate the reader’s reaction; rather, the reader gleans his or her own conclusions from Baby’s reminiscences or the unnamed witness’s forlorn love.

The successes and misfires of Orientation ultimately hinge on the same thing: trusting the reader. When Orozco trusts his readers to orient themselves within the diverse structures and psychologies of his stories, they are copiously rewarded. When he does not, however, the stories start showing off, overcompensating, explaining themselves too forcefully. “Feel free to ask questions,” the speaker in “Orientation” tells the reader. “Ask too many questions, however, and you may be let go.” For Orozco, the sentiment is similar, albeit inversed – reveal too many answers, and this relationship may be terminated.

This post may contain affiliate links.