by Emma Schneider

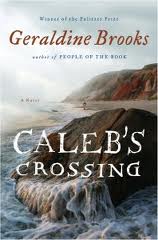

Long, long ago in a rough-hewn version of what is now known as Martha’s Vineyard, a headstrong young Puritan girl met the first Native American man to graduate from Harvard College. Though Geraldine Brooks names her latest novel of historical conjecture after the determined Wampanoag, Caleb, her account more closely examines the perspective of its’ narrator, Bethia, than that of its purported subject. In Caleb’s Crossing, Brooks threatens to offer a shockingly stereotypical account of the coming of age of two individualistic adolescents in a close-doored white man’s world, yet she manages to direct her story slightly away from the beaten path. Caleb’s Crossing investigates the development of Bethia’s understanding and acceptance of her patriarchal and Puritanical society in tandem with Caleb’s internal struggle, which is instigated by seperation from his home culture.

Intelligent enough to make the white men around her uncomfortable, Bethia struggles to keep her tongue bridled and gallops off to the other end of the island where she secretly befriends a mysterious Native American boy just her age. Amidst the clam digs and blackberry bushes, each child tiptoes into the other’s world.

Yet, Caleb’s Crossing is more a story of loss than of discovery. From the all-too-common deaths plaguing the island residents to the collapse of hope riding in the wake of perished loved ones, it tells of lost culture and possibility. Bethia drops the freedom of childhood for the constraining duties of womanhood. Caleb abandons his history in the hope of claiming a place in the future. Before leaving for Harvard, Bethia and Caleb discuss his reasons for disavowing his beloved culture for one that destroys so much of what he admires.

‘You ask why I eat with you, learn your prayers. Why I study to hate all that I once loved. Put your ear to the sand. You will hear my reason.”

I tilted my head, puzzled.

‘Can you not hear? Boots, boots, and more boots. The shore groans under the weight, and yet more come. They crush the life from us.’

Even as Caleb envisions the harsh future of his people, Brooks lingers in the possibility that a significant number of white settlers had functional, if not positive, relationships with their Native American neighbors. What if a classically educated Native American had stood as lawyer, translator, and bridge between the settlers and the native peoples? Bethia voices a modern frustration with the brutality and ignorance of European explorers. As the reader slips into Bethia’s quick-witted mind, she imagines herself as the sort of white settler she should like to be: open-minded, curious, and hearty. The novel plants seeds of a wish-fufilling peace, the sprouts of which the modern reader knows to have withered.

Scattered with period phrases and grammar, Brooks lends her narrator a voice that is far from authentic. Such a cautious sprinkling of period dialect proves somewhat distracting, as it is not frequent enough to settle into the text. A more complete adoption of 17th century writing habits, however, would surely have proven far too daunting for all but the most determined of modern readers. As stated in her appendix, the accounts of early American women such as Anne Bradstreet inspired her writing, but she did not strive to imitate them. Brooks seems not to have sought realism in either her format or her prose, but simply a form that harkens to the period she recreated.

The appendix confirms that Brooks’s many images grew from rigorous study of the meager scraps history could offer her. For example, Caleb really did graduate from Harvard, though his one letter tells historians little else of his life. Location also features prominently throughout the novel, and Brooks’s conjectural descriptions of early sites in American history read vividly and believable. Brooks shines in her loving descriptions of the island that is her part-time home.

“Crossing” implies as many meanings as a picture does words; Brooks stiches them all into her thoughtful sampler of early American life. Not only does Cheeshahteaumauk accept his new life as Caleb, he must sail over waters to reach his school, and sit on a Christian pew. He bears with discrimination; he accepts the one-way road from the land of the living to that of the dead. Bethia sees herself as a servant of God, and though she was not part of the great crossing from England, Bethia represents her budding community. Most of all, Brooks focuses her novel on the crossing of two paths—that place where people meet, part, and choose their course.

This post may contain affiliate links.