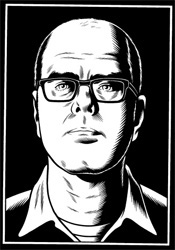

Charles Burns

Charles Burns

in conversation with Jesse Montgomery

Charles Burns has been a luminary of the alternative comics world since the early 80s when his work began getting published in the underground comics anthology RAW, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly. Burns is most famous for his decade-spanning, highly praised series Black Hole, published between 1995 and 2005 by Kitchen Sink Press and Fantagraphics. The series chronicles the misfortunes of a group of Seattle teenagers who contract a horrifying sexually transmitted disease which leads to gruesome physical disfigurations and social chaos. Burns is also the in-house illustrator for The Believer.

His latest work X’ed Out is the first installment in a new trilogy. Printed in brilliant full color, the book follows a young man named Doug as he drifts in and out of sleep-like states, flashbacks and what seem to be full-on drug-induced hallucinations. We sat down with Charles Burns in his home in Philadelphia to talk about X’ed Out, Black Hole, and teenage vampire romances.

“Dark” and “sophisticated” are two words that are frequently used to describe your work. Do you think more people are becoming interested in reading comics marketed as “serious comics”?

I’ve never really – and this sounds stupid because I’m working in a commercial medium – but I’ve never thought about an audience, or written for a specific audience, per se. I’m just trying to pull together my ideas in the best possible way, and I’ve never tailored those ideas for a particular audience. I bet I could do a pretty good teenage vampire story, for example. It would have plenty of romance, and just the right amount of titillating sex, but I think I’d wind up out on the Ben Franklin Bridge looking down at that water and thinking it looked pretty good down there [laughs]. I’ve really tried to put blinders on and just tell my stories the best way I can.

Before its release, there was precious little information circulating about X’ed Out – your latest comic and first major release in a few years – so to start, what is X’ed Out?

See that’s where I’m gonna stumble every single time I get interviewed. The story is partially about a protagonist named Doug. It takes place in the U.S. in an undisclosed city at the end of the 70s. When I started… let me back up…Originally, when I was finishing Black Hole, I started taking notes for a story that would take place during the punk era in the U.S. I was around the Bay area punk scene from 1977 to 1979 – it had a real impact on me – and I wanted to do a story that dealt with that subject matter. Part of that would involve – I hate to use the word experimental – but slightly more experimental story telling, imagery that would come out of a character’s subconscious, and a less typically linear narrative path. So what I started doing was putting together a story that followed two threads: one is an almost fantasy world that has this unnamed character who looks like he fits into a more cartoon-y sort of world that comes out of the Franco-Belgian cartoon style that Hergé popularized, and the other thread is more in line with the way that I would draw and work, and deals with this damaged kid Doug, who is telling his story in a very elliptical way. He’s kind of broken and the storytelling mirrors his thought process as he looks back on his recent past and examines it. And speaking of elliptical, there’s my very long-winded, not very clear explanation.

You wrote Black Hole over the course of about ten years. How does such a prolonged writing process affect a single work or a single storyline?

Comics were always work that I did for myself, primarily. I did commercial work and advertising to pay the bills, but my comics were work that I had to start and stop on over a long period of time because of the logistics of taking on more jobs, dealing with the real world, raising a family and so on. But when I look back, I think there are benefits to having that process of starting and stopping. I think if I’d barreled through with no distractions it would have been a very different kind of story. Instead I had a chance to step back from it occasionally and reflect on how I wanted to proceed.

Can you notice the readership changing through a process like this? Did the series become more popular, less popular?

I really don’t have much of a hold on what my readership is. Occasionally I’ll do book signings or things like that and I’ll meet people who read my books, but when I started Black Hole the process was fairly typical if one was working for an alternative publisher. The idea of putting out a pamphlet – a traditional comic book – and serializing a story was fairly typical. There were a lot of people who were putting their work out that way. Chris Ware was doing Jimmy Corrigan serialized in his Acme Novelty Library, Dan Clowes was putting books together through his Eightball comics, Joe Sacco was serializing various stories that would eventually be collected in works like Palestine. Anyway, it was sort of standard practice at that point, and if you were a fairly popular artist and had a fairly consistent readership you could actually, kind-of, sort-of make a living on selling those pamphlets. I think Black Hole did okay when it was serialized, and I think there was a consistent readership. But I always anticipated putting the whole story together because it was made to be one long story, and I think that when it was collected it found a much wider audience, and a very different audience.

Do you think that is going to be a strange experience for readers who are primarily familiar with graphic novels or collected works to read X’ed Out, which is being released serially?

I think it might be. I’m releasing the book in kind of an odd way. I’m taking this Franco-Belgian style of book – their version of our comic pamphlets – a hardbound book that’s not that long, not a giant read, and putting out a series. Mine does end with a cliffhanger – it does end with a kind of “to be continued” sort of thing – which I could imagine would be frustrating for some people, but when I started writing the story, I wanted to have it in segments like this. There are going to be three books in all, and I think as the next two books come out it will be clear why I made that decision. Hopefully it will be clear why I made that decision [laughs]. It does tell a complete story, but I’m not really doing it the same way I did Black Hole, it’s a different experience. When the book was being sold, a publisher was like “this is a really short graphic novel” because now this term ‘graphic novel’ is a term everyone knows. But, if you do something that doesn’t conform to that, suddenly you’ve created this other thing. It’s not going to be a graphic novella, or whatever. It’s what it is. This is the form I wanted to use to tell the story.

Both Black Hole and X’ed Out are concerned with teenage alienation, teenage sexuality, teenage self-medication, but the tenor of each work is very different. How would you say that being young and disaffected in the world of X’ed Out is different from being young and disaffected in the world of Black Hole?

In my mind, it’s kind of inching up there in age. Black Hole takes place in the early 70s, maybe ’73, and X’ed Out takes place starting around 1977. So I guess it’s the difference between being 17 and being 21 [laughs]. There’s a slight difference there, a slightly more world-weary attitude held by the main character in X’ed Out. And, as the story progresses, he’ll actually be aging as well, so it’s going to spill over into the early 80s. For me, I think Black Hole really dealt much more with high school students of that era. It took place in Seattle because I grew up there and it was really about the people that I knew, the places that I went and the things that I felt during that time period. The same thing is true with X’ed Out, but in a different sort of way.

Another noticeable difference is the presence of punk rock. What did punk rock do for teenage alienation?

Well, for me it was refreshing. I had, in my own way, been pulling away from the prevalent feel-good, post-hippie popular world that was surrounding me and I was starting to explore the edges of all these different things that were out there. But when punk came about, it was refreshing. There wasn’t a bloated, overweight sound to it. It was stripped down. I know it sounds stupid now, but there was this whole DIY attitude that you and your friends could start a band, play music, put out a 45 for a little bit of money, and do something for yourself. You could take control of your life instead of being reliant on the record industry or the publishing industry. There was also something liberating about being able to acknowledge a darker side to one’s psyche, that everything wasn’t about peace and love. Maybe that’s unfortunate, but that was also the reality, that was the truth.

And there was also something very urban about punk that was very attractive to me. I think before that I’d had this kind of fantasy that I’ll live in this kind of Utopian – I’m joking here a little bit – but that Utopian hippie dream of being out in the country, but punk was more about inhabiting this shell of a city, living in an area, where mom and dad have left the city and you’re left to play around as you see fit.

The Washington Post once praised your “particular genius for the grotesque.” Do you ever feel the need to take a compliment like that with a grain of salt?

There are plenty of comments I try to take with lots of grains of salt. But yeah, I have an interest in grotesque imagery. I couldn’t point exactly to why that is. I can speculate and think about things I grew up with and looked at and was drawn to. My dad had a book that had Daumier prints of headless corpses and I looked at that a lot. I probably shouldn’t have been looking at that, I was in preschool. But that’s what I did; I sat around the house looking at books. So I’m looking at Daumier. So its his fault. It’s a lot of people’s fault… There’s a kind of vitality there [in the grotesque] that I’m attracted to, as hard as it is to express. But I try not to pay attention to whatever those publicity lines are… I’m the David Lynch of comics, in case you didn’t know [laughs]. Dan Klaus used to be the David Lynch of comics and, well he probably still is. We’re both probably the David Lynch of comics…unless I’m the Cronenberg and he’s the David Lynch…

All images courtesy of Charles Burns.

Portions of this interview originally appeared in PLANET.

This post may contain affiliate links.