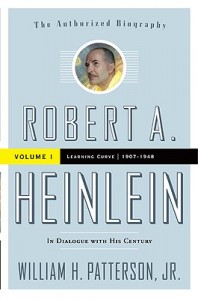

[Tor; 2010]

Robert Heinlein’s best known works, Starship Troopers and Stranger in a Strange Land, seem almost as if they were written by different people. The former is a tract of military fetishism exploring crypto-fascist notions, the latter concerns an orphaned earthling raised on Mars who creates a free-love revolution on earth. From these works, I knew Heinlein was carrying around contradictions. But it wasn’t until I began to read William Patterson’s biography of Heinlein that I realized how important those contradictions were in expressing the Geist of an entire generation.

Born in the Midwest, Heinlein moved to California after attending the United States Naval Academy and serving honorably until being discharged. Briefly involved in Democratic politics, Heinlein began experimenting with a unique brand of Libertarian politics in the 1950s and participated, to an extent, in the burgeoning Libertarian scene. By the mid-sixties he was even stumping for Goldwater. He became an advocate of free-love, free-markets, and an almost neo-colonial type of space exploration. And he advocated for all of this with the kind of positive gusto post-war America was infamous for. Although not a Boomer himself, he was a sort of Ur-Baby Boomer. He was both a product of and an advocate for all of the peculiar passions and flaws that the generation just junior to his would use to transform popular culture.

Besides being one of the first of his time to make that journey from youthful liberal idealism to middle-aged libertarian utopianism, Heinlein advocated space travel — colonization for, from what I can tell, colonization’s sake. He explored the idea of ethnobiological weaponry like lasers that would only kill certain races. He claimed to abhor racism and made many of his lead characters persons of color. He compared communists to insects and glorified their mass-extermination. He was obsessed with personal freedom. He invented fantastical concepts like “groking” in order to deal with existential loneliness. He helped commercialized Science Fiction unlike any author of the genre before him. He coined the phrase “moonbat.” He seemed to advocate, or at least be comfortable with, the concepts of polyandry, polygamy, and incest. He advised Reagan on the Star Wars Defense System. His description of a waterbed predated their mid-century mass production.

If any of this feels familiar on a fundamental level, it’s because it is. The whimsies and preoccupations of Heinlein have become identical to the most tedious aspects of our contemporary culture. They have become one and the same. And although Heinlein was certainly an agent of the post-war shift in consciousness, he was also an artifact of the change itself. It’s telling that the only blurb on the advance copy of the book is from Tom Clancy, another embarrassing boomer who took a modicum of real world experience and transformed it into entire alternate realities — more imaginative space in which their inflated egos could graze. And the most disturbing aspect of their commercial and cultural success is that yesterdays self-indulgent baby boomer fantasies always seem to transform into tomorrow’s policy papers. Heinlein helped to create the Boomer fantasy world in which we now live.

I walked into “Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century Vol. 1: The Learning Curve”, expecting to find an overly-cohesive story. Biographies, especially authorized ones such as this, sometimes let hindsight and fandom cast a cartoonish and misleading clarity on the subject. What we end up gaining in a simple and straightforward narrative we end up loosing in an honestly confused keyhole glimpse at another human. Which is to say biographies should be more in the business of suppressing myth-making than, even inadvertently, creating them by trying to fit disparate elements into a coherent storyline. This book in particular, partisan as it is, excels at placing Heinlein in his time and place. The questions the text raises about a thinker’s place in culture might be asked inadvertently, but drawing on such a rich subject, those questions are impossible to avoid. Instead of asking us to whittle Heinlein the man down to fit our preconceptions or our politics, the book challenges us to instead engage in exploring his complexities.

This post may contain affiliate links.