In his relatively brief life, Steve Abbott was many things: poet, novelist, theorist, community organizer, gay rights activist, single parent, and an originator of the New Narrative movement. Between the 1970s and his death from AIDS-related illness in 1992, he traveled widely across Bay Area literary and artistic circles. Since his death, his work has been beloved by a devoted few. Now, with Nightboat Books’ publication of Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader, Abbott is primed for a reappraisal by the initiated and discovery by a new generation of readers. What follows is an interview with poet Jamie Townsend, editor of Beautiful Aliens.

In his relatively brief life, Steve Abbott was many things: poet, novelist, theorist, community organizer, gay rights activist, single parent, and an originator of the New Narrative movement. Between the 1970s and his death from AIDS-related illness in 1992, he traveled widely across Bay Area literary and artistic circles. Since his death, his work has been beloved by a devoted few. Now, with Nightboat Books’ publication of Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader, Abbott is primed for a reappraisal by the initiated and discovery by a new generation of readers. What follows is an interview with poet Jamie Townsend, editor of Beautiful Aliens.

Joseph Bradshaw: I’d like to begin with you providing a little background on Abbott: Who was he? What was his place within the Bay Area literary world?

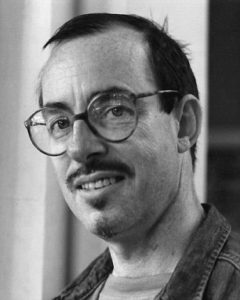

Jamie Townsend: Steve is a pretty unique figure in the history of Bay Area writing. Like a lot of queer young men in the 1970s he was a transplant to SF, but unlike many others he was a recent widow (his wife Barbara died in a car accident just months earlier) and a single parent, moving there from Atlanta with his young daughter Alysia in early 1974. When he arrived he threw himself into a number of writing, art and organizing projects. This work seemed both informed by his new locale and a natural extension of his previous experiences as a social justice advocate and conscientious objector during the Vietnam War (a position he was almost jailed for as a draft dodger), comic artist, writer and editor/publisher. Steve’s idiosyncrasy, in part, comes from this mélange of varied skill sets and lived experiences, but also from his position as the father of a young girl, living as an out gay man in the middle of a robust queer community where parenthood was not the norm. I think this added layer, being a young, single gay father, provided social difficulties, but perhaps gave his work a sense of urgency and perspective as well. As a working-class writer and a dad at the same time, Steve knew how to hustle.

Here’s an example. In his essay “My Kid,” which is composed as an interview to himself, Steve talks about this difficulty of being a single gay parent and the complex relationship he had with Alysia. His solution to feeling marginalized within a marginal community? He helped found a gay fathers’ organization in San Francisco. So, it seems like it was in Steve’s nature to create spaces that didn’t previously exist to address his own needs.

Steve Abbott

One of the spaces he helped create was a community of writers that later came to be known as New Narrative. How was he involved, and what is his place within the New Narrative canon?

It’s interesting to think of “the New Narrative canon.” Until pretty recently it was a movement mostly local to the Bay Area and, as NN writers themselves have admitted, a “school” most likely to be resigned to obscurity. The important work that writers and editors such as Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Rob Halpern, Robin Tremblay-McGaw, and Eric Sneathen (among many others) have done in contextualizing and tracing a history of NN has helped rescue it from the potential dustbin and foster its current widespread interest. Whether it’s primed at this moment for a sort of canon making or (shudder) institutionalization is up for grabs, though it seems like that’s an eventual inevitability. What may stand in the way of this is the fact that “New Narrative” means many different things to many different people, even for those who were there at the beginning, like Steve, talking about what a “new narrative” might look like. Bruce Boone once commented to me that New Narrative wasn’t a literary movement, but rather a small group of friends sharing work with each other (he limited this list to himself, Bob Glück, Steve, Kevin Killian, and Dodie Bellamy). Dodie and Kevin, with their vital Writers Who Love Too Much New Narrative anthology, take an opposite stance, displaying a rangy collection of writers outside this small group of friends who—while often sharing social connections and certain aesthetic affinities (sex writing, autobiography, gossip, metatextual analysis and running commentary, hybridity, etc.)—were actually quite different. There are also some excellent essays that flesh out New Narrative as a style or mode of thinking, including Bob Glück’s essential “Long Note on New Narrative” where, among many other fine insights into his writing practice, he describes its efforts to collapse seemingly opposed thoughts and impulses: “To describe how the world is organized may be the same as organizing the world. I wanted the pleasures and politics of the fragment and the pleasures and politics of story, gossip, fable and case history; the randomness of chance and a sense of inevitability; sincerity while using appropriation and pastiche.”

Steve, for better or worse, coined the term “New Narrative” in the introduction to the second issue of his DIY literary and arts magazine Soup, to reflect a moment in writing where certain modes and interests played off each other to represent overlapping communities of resistance in dialogue. He writes: “New Narrative is language conscious but arises out of specific social and political concerns of specific communities… It stresses the enabling role of content in determining form rather than stressing form as independent from its social origins and goals.” It’s interesting because he is discussing this new form of narrative writing in relationship to LANGUAGE poetry, the dominant post-modern school of writing in the Bay Area at the time. Narrative becomes a place of “both and,” an adjustment to LANGUAGE’s deconstruction of content and the removal of authorial perspective through political discourse and theory. Steve notes the importance of writing emerging from marginalized groups that have unattended needs which, to attend to, require difficult, relational work.

Steve’s later essay “Notes on Boundaries: New Narrative” details a complex intersection of writing, visual art, and social justice work. In it, he’s attentive to different social and aesthetic boundaries, as well as where they blur together or disappear entirely. This also has a lot to do with being queer—a queer phenomenology, to borrow Sara Ahmed’s term. “When women, gays, and ethnic writers bring back narrative, why is it different?” he asks. I think New Narrative for Steve was simultaneously a political practice and an art practice. He persistently comes back to the examination of personal relationships (between friends, lovers, comrades, fellow artists, even enemies), how they can function as a model for larger dreamed about systemic changes, and how writing can be used to move us towards these spaces by shifting perspective. It’s a simultaneously grandiose and humble assertion—the importance of the individual for their ability locate themselves within a larger web of narrative. Steve’s writing often asks the reader to be open to self-critique and surprise, to be open to the process of discovering new avenues for thought, whether hyperbolic, or crass, or even wrongheaded; to create visibility and spaces for traditionally silenced voices to take center stage and speak freely. This is where Steve, as a publisher, organizer, editor and critic really excelled – by providing a sense of permissiveness for this new narrative to exist.

I like that you emphasize he was as a champion of marginalized voices. It’s important for contextualizing his work, and it’s especially relevant now. What do you hope readers new to Abbott will take from it?

This gets back to what I was saying about this current moment of interest in New Narrative. Expanding on that, the intersectional work a lot of New Narrative writers were doing speaks very directly to the current political landscape. Steve’s interest in marginal writing—that is, writing that emerges from groups that have historically had little say in both the mainstream and the avant-garde—is reflected in the efforts of publishers, activists, and artists themselves to spotlight and shift focus towards groups that are still resigned to these margins: queer voices, trans voices, POC voices, victims of abuse, female-identifying voices, immigrant voices. We are living in a time where the field of visibility and access to information is simultaneously wider and more obfuscated, so the need for this kind of focus—as well as the return of trailblazing marginalized voices such as Steve’s—is vital.

Although many of the essays are time and location specific in their details, their general themes are still very resonant. Steve’s essay “There Goes the Neighborhood” details gentrification in San Francisco. “Dialing for Sex” and its examination of technology, intimacy, and sex predates the ubiquity of internet porn by more than a decade. Steve’s most well-known work, “Lives of the Poets,” pieces together snippets of autobiography from a multiplicity of sources to form a single story. I think this constituent body speaks to queer experience in general, and, as a gender fluid and plural identifying individual, to myself in particular. My hope is that readers would be able to find connection in the voice of someone who even 30 years ago was struggling with similar feelings. I think that the work in Beautiful Aliens represents the vast variety of subjects, styles, and artistic practices Steve pursued during his life, and the sheer variety alone is appealing. There’s a permissiveness to Steve’s “jack of all trades master of…some” approach that is inviting and lends credibility to his practice. The rawness of style enriches the rawness of the subject matter.

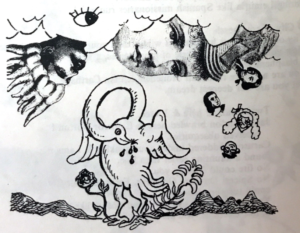

Speaking of the sheer variety of Abbott’s work, Beautiful Aliens includes a selection of his illustrations and comics, many of which offer wry commentaries on the poetry communities in which Abbott participated. These comics seem a clear precursor to the work of poet-artists such as Bianca Stone and Sommer Browning, among other current practitioners of comics poetry. What was the context for Abbott’s comics? Where did they first appear?

Speaking of the sheer variety of Abbott’s work, Beautiful Aliens includes a selection of his illustrations and comics, many of which offer wry commentaries on the poetry communities in which Abbott participated. These comics seem a clear precursor to the work of poet-artists such as Bianca Stone and Sommer Browning, among other current practitioners of comics poetry. What was the context for Abbott’s comics? Where did they first appear?

Steve’s comics are interesting as they can be seen as both the stylistic outliers in the collection and, perhaps, the most straightforward pieces at the same time. They do that great New Narrative fourth wall breaking that removes the self-seriousness of the poetry world at large. I always laugh at “The Vertigo of Loss”, the comic poem that opens Steve’s collection Stretching the Agape Bra. The premise is both wry and absurd. The main character, Lester, finds a “beatnik rib” on the street and uses it to prop up the end of his recently acquired “punk couch.” With the addition of the rib the couch begins to speak, spouting some florid, faux intellectual doggerel. Lester realizes he can make some cash off it during open mic at “The Olde Baloney Factory.” Steve’s goofy critique of both post-beat open mics and the opaque ridiculousness of postmodern writing teeters on self-parody and perhaps even mean-spiritedness, but it’s just weird enough to get away with it, poking a little fun at himself along the way.

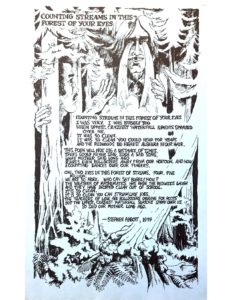

The comic poem is not a form innovated by Steve (the lineage of modern verse illustrators stretches back to writers like Joe Brainard, Kenneth Patchen, and, even earlier, William Blake), but Steve’s illustrated verse is truly “comic” in that it’s drawn from popular comedic work in illustrated form: the Sunday funnies, counterculture comic book artists like R. Crumb and Zap Comix mainstay S. Clay Wilson (who was a friend of Steve during his college years), and pornographic “eight-pager” pamphlets. As I spent time in Steve’s archives I found doodles, half-finished strips and comic poems scattered throughout his papers. Steve was an illustrator as much as he was a writer, and some of his earliest work, from the late 60s to early 70s, was in comic form.

Steve also spent a good deal of time organizing readings, as well as self-publishing chaps and magazines, so the comic poem form became central to his larger practice; many of the illustrated pieces in Beautiful Aliens were published either as flyers/broadsides for events in the Bay Area, or were included in Steve’s literary arts journal Soup. Aside from it being a practice that supplemented his own work, it became a way of grabbing the attention of a passerby that might not otherwise look at a flyer for a poetry event. Steve’s archive contains several illustrated books and many small comics that either feature or are dedicated to his daughter Alysia. Poetry comics and illustrated books became a way for Steve to both connect with her and provide fuel for the fantastical, comedic atmosphere of his poetry and fiction at the same time.

I’m glad you brought up Abbott’s archive; I want to know more about your editing process. Can you talk about the resources you had in your research and your criteria in selecting work for the book?

I’m glad you brought up Abbott’s archive; I want to know more about your editing process. Can you talk about the resources you had in your research and your criteria in selecting work for the book?

It’s sometimes strange to imagine performing this recuperative work having never met Steve (I was 11 when he passed). Looking back on the process of editing the book, I think that without ever having a face-to-face relationship, it’s been similar to having a dialogue with a trusted writer friend who lives far away.

About 4 years ago Kevin Killian, Steve’s literary executor, clued me into the archives. I hadn’t started the process of putting together a book proposal, but I had read enough of Steve to be interested in seeing more of his work up close. Steve’s archive is located in special collections at the James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library and I arranged to view the collection in the winter of 2015. My first visit to the archive was with the plan to scan and begin digitizing a small collection of Steve’s work for my own New Narrative studies, including his unpublished first novel Lost Causes. I think that my first visit there I barely got through one box of materials. Folder after folder yielded a wide variety of writings and artworks, including early journals detailing his first openly gay relationship (while he was still married to his wife Barbara) and his first trip to SF, as well as court documents from his trial for draft dodging as a conscientious objector. As I hunted through these material, I felt increasingly connected to his story and began better understanding the key events and fixations which formed a through-line to his wildly varied practice: unrequited love, queer revolution, esoteric fascination, the fear of obsolescence.

Soon after, Kevin also put me in touch with Steve’s daughter Alysia, who spoke with me about her father’s work beyond the context of biography (as her Fairyland memoir does beautifully). When I started working on the book with Nightboat she was a source of information and further consideration of the range of materials available. She pointed me to illustrated poems that where beautifully drafted on 11×18 broadsheets, that include tiny pine forests, crying giants, and men with flowers growing out of their hair, each bordering bubble-scripted lines of poetry. Looking through all this, everything seemed to be converging together in one place.

I think spending a lot of time in the archive confirmed what I already assumed about Steve’s work. His published books of poetry are scattered with comics and photography and prose explanations, and his archive was a supersized version of that. So, I think the archive became my ideal model for putting together Beautiful Aliens. It was trusting in the natural affinity of the various materials, seeing them as codependent and creating a larger more coherent whole.

Reading Steve requires a certain level of self-awareness. Being able to understand how a critique leveled at a particular cultural artifact or an examination of a particular autobiographical circumstance helps readers to understand the dynamics of queerness in the contemporary sense. How being “outside of” or “in opposition to” is not an aesthetic, but rather a phenomenological stance. I was speaking with a friend today about Steve’s essays and why I find them really vital. In them Steve writes a lot about life in the 1970s and 80s, as well as life as a gay man in San Francisco during those years. On the surface it would seem that a lot of these essays, which examine largely bygone phenomena such as phone sex, or local attractions like the Stonestown Mall in SF, are useful within a particular frame of reference linked to the years Steve was alive. However, Steve’s permissiveness in using seemingly banal or obscure topics to explore complex expressions of desire, shame, isolation, or resistance speaks to the timelessness of a lot of similar work that might be labelled dated. This is not to say that all of Steve’s writing is for a contemporary audience, but the best of it asks the reader to participate in expanding the discussion beyond its seemingly humble origins; he risks being wrong or silly in order to ask questions to his readers. In his essay “Notes on Boundaries: New Narrative” Steve writes: “The meaning of experience isn’t always obvious. Borders shift.” Then later, “truth, love, friendship, lust, community—everything gets mixed up.” It’s statements like these that, for me, really get to the heart of Steve’s project. He’s not looking to instruct, he’s interested in a deeper understanding of his own limitations, and, consequently, ours as well.

Do you think Abbott has been undervalued?

That’s a tricky question. I have a knee-jerk response that wants to ask about whether Steve has been given the opportunity to be evaluated at all yet. I guess if value is based on credit received from doing the supportive labor that is critical for work to be produced in a small writing community, then there are glimmers of appreciation (most notably in Bob Gluck’s essays and in Kevin and Dodie’s anthology Writers Who Love Too Much). Ariel Goldberg also devotes a section of their book The Estrangement Principle to exploring Steve and his work in and around the formation of New Narrative. Other responses have been cursory and at times dismissive, but are often couched in social circumstances and interpersonal histories where I don’t have enough firsthand experience to make an informed evaluation.

Steve was, in a lot of ways, a cheerleader and PR person for the different groups of writers he was involved in. He organized and created flyers for events, published a magazine that featured his friends’ work, and wrote reviews and articles in SF periodicals (including the Bay Guardian, Poetry Flash, The Advocate, and The Sentinel, among others). This supportive work is critical for the creation and growth of artistic communities but, as is the case with most organizational efforts, is not often the work that remains in the spotlight. It’s a shame, but unfortunately a matter of fact, and an attitude that I hope we can change moving forward. I guess that Steve is undervalued in this sense, but he is just one of countless people that work in these supportive roles that too often fall by the wayside and go unrecognized. I hope that this selection of Steve’s work—in addition to giving a wider audience to Steve’s idiosyncratic writings and visual art—displays his commitment to the time, place, and communities he was working within.

Last question. How has your involvement with Abbott’s work affected your own writing?

Last question. How has your involvement with Abbott’s work affected your own writing?

Two touchpoints for me as a writer are Steve’s poem “Elegy” from Stretching the Agape Bra and his book “Lives of the Poets.” Both progress with an earnest lyricism and are constructed from a variety of biographical sources collaged together in a way that has been especially helpful as I’ve begun to explore a non-singular identity in my own poetry.

Outside of his fiction and poetry, I have definitely been challenged by Steve’s rapacious inquisitiveness and dedication to the place where he lived, as well as his friends and contemporaries. His essays, touching on everything from high art to low-brow and quotidian investigations, have been incredibly encouraging to me in their permissiveness. Steve’s writing life seemed to extend seamlessly from his day-to-day, and when he names names and opines over his own fascinations, frustrations, and obsessions, he does so in a way that never feels studied. Yet even at his most amateur, he is never simplistic. I like the questions he asks about what community looks like, how to develop a sense of attentiveness toward blindspots, how one can find strength in the midst of incredible sorrow; I think these are lessons that are still applicable to our own contemporary struggles.

Steve has also encouraged me to develop a more consistent practice of reading my friends and writing about their work. That’s due, in part, to his own long-running series of book reviews and interviews in Bay Area publications. Over the past few years I’ve attempted to make writing on the work of those in my own community part of my writing practice. His shoes are quite big to fill in this regard, but his enthusiasm is infectious and has brought a measure of joy to my life as a writer not just among, but in relationship with other writers, artists, and activists.

Joseph Bradshaw is a poet, essayist, archivist, and educator currently based in the East Bay. He is the author of In the Common Dream of George Oppen (Shearsman Books) and The New York School (Publication Studio).

This post may contain affiliate links.