“They invited me into their home and within a week I was discussing its telegenic potential with a reality show producer responsible for nothing I’d heard of.” This is the opening line of Exquisite Mariposa, and it gestures towards a major plot point in the novel. But it tells you nothing at all about what will soon unfold, as Fiona Alison Duncan explores the complexities of contemporary girlhood and the experiment of being authentic in 2019.

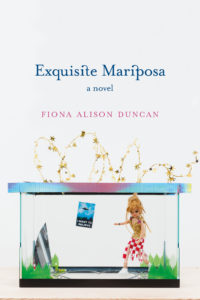

Exquisite Mariposa tells the story of a woman in her late twenties named Fiona Alison Duncan — a fictionalized version of the author. Fiona is early into her Saturn Rising (finally, you’ll know what that means), who moves into an apartment in a building called La Mariposa in Los Angeles. As hinted in the opening line, Fiona quickly becomes so enchanted by her roommates and their shared conversations that she decides they deserve to be filmed, and somehow manages to land them a reality TV deal (“It would be Reality Bites meets Tumblr, The Virgin Suicides but healthful. Young-Girl, art world, recession America, Survivor! A real Real World. The IRL World”). Oh, and Fiona is also romantically entangled to a fuckboy. This is the basic setup of Duncan’s novel, which is by turns bildungsroman, stream of consciousness, cultural polemic, L.A. novel (think Eve Babitz meets Kate Braverman), and a tender love letter to her friends.

As you can see, Duncan’s novel cannot be squarely categorized. Its first bites taste like mainstream contemporary fiction; they go down easy, like candy, or like a Sally Rooney novel. But as you continue to chew — because this novel is chewy — you encounter something quite different. By the end, this novel has spun in all directions, like a piece of thread from your favorite Vetements shirt coming undone.

Duncan’s novel begins with a quote from the unpublished notebooks of Kathy Acker: “I have always been a girl. I have never had a strong sense of reality because I’m a girl.” Starting a novel with a Kathy Acker quote sets Duncan up for a daunting task. She is telling the reader who her influences are (which she ultimately wears on her sleeve), and, whether on purpose or not, that she deserves to be compared to them. Consequently, as a reader you cannot help but be on the lookout for Ackerisms. Which is why it is a pleasant surprise the majority of the novel reads like something contemporary and a bit mainstream — meaning, very unlike Acker. But there is a subversive novel underneath this initial sugar coating, something rebellious and cutting and experimental. It is not until the latter half where you realize Duncan has been driving you a bit off course and into new, less conventional territory. Which is to say, Duncan subverts expectations of contemporary narrative. Instead of following more typical narrative beats, and instead of arriving to a cliched happy ending, Duncan reveals her novel to be a quiet exploration of the fraught relationship between contemporary girlhood and authenticity, with meandering final chapters constructed of philosophical digressions and poetic fragments.

Exquisite Mariposa is less about plot and more about Fiona’s internal conflicts. When it comes to plot, the biggest throughline is the reality TV deal. Fiona desperately believes her and her roommates deserve their own reality show because, with them, it would be “real”:

We’d talk about it all: infinity, etymology, astrology, spirituality, empathy, epigenetics, trauma, rape, race, class, sex, gender, technology, fashion, art, Justin Bieber, black holes, souls, The Matrix, fractals, spirit animals, family, branding, anxiety, the economy, conscious capitalism, collective consciousness, consciousness raising, Kundalini rising, twin flames, nail care, nicknames, rage, age, real estate, acid, Vine, love, and what we should make for dinner.

They have real conversations on class, power, technology, capitalism, feminism, politics — everything that plagues the well-educated, “woke” millennial urban set. To think one’s conversations are more interesting and more intelligent than others’ is self-gratifying and presumptuous. However, I cannot help but admit that my friends and I have had late night conversations that have left us feeling similarly. After talking for hours, we’d confess and share the intimate thought that we should have recorded ourselves. This impulse, and the narratives surrounding it, are not new.

Linda Rosenkrantz’s novel Talk, for example, explores this drive to make public, or to broadcast, our intimate thoughts. Talk, published in 1968, is allegedly a transcription that has only been slightly edited of her summer spent recording her conversations with her friends. It reads more like a play, but the intention is similar: to make a record of your life as it happens. An issue Rosenkrantz is confronted with is the heightened performance of her subjects. In knowing that they are being recorded, her friends approach things with more purpose, caution, choreography. The result here is a critique of performance and a questioning of authenticity. Talk is evidence of people’s tendency to over-perform when aware of the permanency — and eventual circulation — of what they say and do.

Megan Boyle tackles the same impulse — to broadcast, to perform, to let others know you exist, all in a continuous loop with no pre-planned ending — in Liveblog. Over the course of six months in 2013, Boyle experimented with live-blogging her life. Avoiding the character constraints of Twitter, Boyle posted live updates on Tumblr instead. The result is a seven-hundred page book detailing the minutiae of daily life. Boyle often describes the most banal of occurrences but, as a whole, Liveblog is quite remarkable. The reader is invited into a stream of Boyle’s consciousness, analogous to a 24/7 video stream of her life. Uncensored. Uninhibited. Vulnerable. Real.

I am not saying that Duncan writes the same as Boyle and Rosenkrantz. The opposite is true, and it is clear that Boyle and Rosenkrantz have very different literary inspirations than Duncan. Rather, there are clear critical and thematic parallels here. On performance and authenticity and boy problems. But also girlhood, and growing up more generally — all roommates at La Mariposa “saw themselves as sharing states of becoming,” and the apartment was a “place girls come to, to grow to be themselves.” Duncan adds to this lineage of novels that confront performance and technology. But, more importantly, Duncan hones in on the experiment that is being one’s true, authentic self — especially under the pressures of society and media — through a femme lens.

“Our conversations, I felt, were in great contrast to the kind of talk trending online,” Duncan writes. But in Exquisite Mariposa, we do not often hear what the conversations between Fiona and her roommates are (sometimes they are just a laundry list of issues, and not so much an analysis), and we are meant to trust that their conversations are more authentic than most and are deserving of an audience and reality TV show. The novel is socially conscious in the way millennial novels from the past few years have been — I am thinking of Sally Rooney, and when it comes to the drudgery of working under late capitalism Exquisite Mariposa shares DNA with Halle Butler’s The New Me. I admit I was a bit surprised to be confronted with a novel so topical, perhaps even zeitgeisty. But Duncan’s novel isn’t just about being of the moment — it just happens to be the case that it is.

Exquisite Mariposa has some things in common with other hyper-contemporary novels: a coming of age narrative, boys, important “issues,” friendships, (briefly) drugs. But Duncan has created a trojan horse here — there’s something more complex at work. Unlike other hyper-contemporary novels, Duncan has the upper hand: in her tactful prose that fuses poetic language with social and cultural commentary, but also through the moments in which she tosses in sharp philosophical ruminations. She challenges the reader by asking lofty questions, by daring them to think about a variety of issues, and by having them swim through the less conventional moments in the novel.

Ultimately, Duncan proves to be a writer’s writer. There is something to respect in writing the novel that you want — an editor at a major publishing house would probably have had Duncan rework much of the latter part of the novel, and would have pushed her to have the one major plot device — the reality TV show deal — become a more dramatic arc, stripping Exquisite Mariposa of its more renegade traits. But instead, we have a bulldozer of a novel that is unafraid of tossing a wide, niche net, then letting the net self-immolate.

Duncan acknowledges the anatomization of narrative within the last few chapters:

This is the part of the book where readers complain I’ve lost them.

“The narrator disappears,” they say. “My attention waned . . . I couldn’t connect anything.”

To which Duncan responds, “Amen.” But to say any more would be to ruin the surprise of the latter quarter of the novel.

I met Fiona Alison Duncan once, by accident. In search for a bathroom in Chinatown, I walked into the East Broadway Mall, a dilapidated, sooty structure under the vibrating Manhattan Bridge. In the basement, I heard a voice echoing, a voice that was also faint like a whisper. Following the direction of the voice, I was soon confronted by a tiny gallery/bookshop, in which a large television played a video of someone reading a passage from a book. Under the television, I could see Fiona, splayed across a soft, cushioned sculpture shaped like an open book. She was on her phone, bored, next to her a stack of Gary Indiana books. I asked for a press release, bought Fanny Howe’s Indivisible, and then found a bathroom. It was only later, while scrolling through Instagram, that I saw Fiona and I realized I was familiar with her work, and soon I was seeing her everywhere (Spike Art Magazine, Affidavit, The Creative Independent). Funny how that happens — when something, or someone, is brought to your attention, and then you cannot help but notice her everywhere afterwards. A feeling I felt reading Exquisite Mariposa as well, a feeling of serendipity itself, of pleasant coincidences and truths and ironies.

Throughout the novel, I could not help but constantly wonder if, when something occurred, it was something Real Fiona had experienced. If the woman I had briefly met had tripped on shrooms in the desert with a kind boy named David, if she really accepted a Franciscan vow of poverty and spent six months walking the city, unemployed, talking to strangers and letting friends buy her coffee, and if she had seriously, like seriously, dated a fuckboy and, more importantly, and more curiously, was the reality TV deal Real? But isn’t that exactly what Duncan wants? For the reader to be confronted with doubts, and to question their place as it stands. To question their lives under social media, and technology more broadly, in 2019, and what this means for the experiment that is society, and personhood.

At one point, Duncan, speaking via Andrea Dworkin, wonders: why do few women experience themselves as Real? This is the closest the novel has to a thesis. Exquisite Mariposa is charmining in its earnestness like that. It reflects how messy and full of curiosity our twenties can be in a manner that reads as true, especially for the creative set. The novel leaves the reader feeling less alone, like we’re all in this communal struggle together. I imagine this feeling is something the television show described in Exquisite Mariposa would have done as well. But we should be glad it became a novel instead.

Josh Vigil is a writer living in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.