Drawing by Goda Trakumaite

This article appeared on Full Stop in March, 2016. I began writing it in my journal in a hospital waiting room in November, 2015. I was waiting to get my IUD out. Before it was even done (before the gynecologist would pull it out of me and tell me I’d wasted it, the precious device!) I already knew: what was happening to me was phenomenal.

Six days post-insertion, I was sitting in that waiting room fuming with copper and wanting to kill myself, maybe others, too. I was hurting, mentally and physically, in ways I’d never before. I was exhausted and in pain. I’d never felt closer, in a way, to my mother, who has multiple sclerosis. Something had opened and I had no idea what was going to happen to me.

What I learned post-waiting room — in the months after when I was presumably recovering from this insane copper poisoning—is that if this was a phenomenon it was also frightfully common, everywhere. Thousands of women all over the world report the devastating turn their life took post-IUD insertion, whether it was in for 3 days or tens of years. Women report, in such a spectrum of ways, that after using this popular and feminist device their health unraveled—in some instances (like me) immediately, and for some more slowly.

I wrote this article (with encouraging collaboration from Features editor Helen Stuhr-Rommereim) and subsequently heard from people who already knew just what I was talking about, or were glad to get this perspective. Some told me they were not going to get an IUD now, some told me they were going to get theirs taken out. Some told me they feel safe and comfortable with theirs in.

This article has needed an update. I published it in the middle of my recovery from this copper toxicity, at a time when I had a lot of new joint pain. I hoped that as I detoxed the copper, I would heal. That’s what the end of this article is all about, getting the IUD removed and moving on. But I couldn’t bend half my fingers. I could hardly walk. At the time, I still hoped for this detox, but what really happened is that my joint pain got very bad. My bones started bending, fingers looking like pieces of hoops, body horror. In May 2016, I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis.

In August of 2017 I started writing Blackfishing the IUD, which — as its published this October — will be the first book to explicitly discuss the negative health effects of this device. I needed a space to say what had happened — to tell and to warn. Not everyone gets autoimmunity but for someone like me, with that genetic susceptibility, this toxic event in my uterus triggered my first RA flare. Autoimmunity isn’t everyone’s story, but others experience anxiety, depression, heart palpitations, hair loss, and joint pain. Through writing Blackfishing I’ve connected with many people who are as charged as I am about this topic, because their lives are irrevocably altered, too. Some of their writing is in the book, as well as a burgeoning set of research that links the IUD with the onset of autoimmunity, and particularly the disease I now have.

So perhaps I just need to say, the positive note this 2016 article ended on — this note of getting to move on — just didn’t happen. Things got worse, and autoimmunity is, like, forever. I am doing a lot better lately, all fingers bending. I treat myself with conventional and alternative (food) medicine. I’m grateful to Full Stop for supporting this article, my experiments, tries, and vulnerabilities, too, as a human but also as a writer. There is room for so much on this website and really, it made the first room for this book.

***

I was 9 as my mother introduced me (at my desperately embarrassed request and my begging) to Jolen Crème Bleach to heal this newish mustache on my face, and she said to me, with a tremulous and whispering (so embarrassing) pride, in my bedroom where we joined crystals to lotion with a disposable little paddle like a laboratory and applied it: “You know, Caren, women have their secrets.”

My mother is sweet, she meant: “I love.” But I thought bitterly even then, tremulous myself and in the midst of requesting this cure — surely, surely there are better secrets to behold among women, and surely Jolen Crème Bleach, this public product, this disgrace of capitalism (invention of a problem, the solution invents it as such) is a poor secret, a despicably shallow revelation. It’s on the shelf.

The Jolene Crème Bleach changed my brown-black hair on olive skin into white-hot-orange, psychotic and so noticeable and so fucking (I was 9) embarrassing. Now I am grown, and I remove it almost weekly with Sally Hansen Crème Hair Remover Kit, which is nothing too private. If you come over to my house, I will wear it for you and make you tea for the ten minutes it takes like the white fluffed up fog of capitalism + women rolling in right on top of my open mouth: I’ve said nothing.

These products are not our secrets.

Things are mysterious. Do you remember the Sphinx in Oedipus the King?: “The intricate, hard song of the sphinx,” “who sang mysteriously,” “It seemed to say we should ignore what we could not see.” It is the sphinx that troubles the fate of Thebes, though no one knows just what it does. How do you discover the inside of stone, the obtuse face? Capital gives us such a look — dumb and hard. I’m frail before it. I’m perilous with my reserves of health and my funds, and sometimes to such consequence. After the latest bad time with women’s health, I am trying to understand better how to read things.

“Women have their secrets.” How to even read this sentence? “Women” is the operative, “secrets” is the alibi, to say it, “Women,” the word, it puts me right in it.

In November, I had the copper IUD, called Paragard, implanted in my uterus, to ensure a 99% chance of unconceivable fucking. I was sick of fucking and fearing conceiving. It goes without saying that I wanted, like many who fuck men, hot unmitigated cum. I rallied in my mind the other women I know who walk around with IUDs in their uteri no problem. I conjured a sense of empowerment here, of women everywhere saying No to hormones (hormonal birth control makes me feel Suicide) and I just fucking — with Obamacare wings — went for it.

Paragard® is a small, soft, and flexible T-shaped device made primarily of plastic and copper that your healthcare provider places in your uterus at an office visit.

Places, like the language of employment, like a jobseeker is placed within a company and does not ram her way there, pushed in with privilege and lying, nepotism and loose ties, the narrow lace-paths of luck, the accumulation of kindnesses and hard work, you are not placed — to have landed something — no one lands, as we did not land on the fucking moon, you do not only appear: there are voluminous histories of insertions. This insertion took multiple tries, and drugs — Misoprostol, a common abortion pill, softens the cervix. I took it in the morning before my second appointment in the afternoon. In between I went to class to teach Hélène Cixous’s “Laugh of the Medusa,” a call in 1976 for woman to “write her self,” with a body that can overwrite, overriding convention:

This [interrogation of erotogeneity], extraordinarily rich and inventive, in particular as concerns masturbation, is prolonged or accompanied by a production of forms, a veritable aesthetic activity, each stage of rapture inscribing a resonant vision, a composition, something beautiful.

“Write her self.” Female pleasure in Cixous’s essay writes for woman, it takes the reins of writing, but the subject, this self, has to initiate, and Cixous calls her reader to touch herself, to take herself. It is the taking, the touch that takes, and takes back, that sparks a self with which to write. Woman, for Cixous, must become like this, a big thief. In class, I felt I would faint from the Misoprostol, feverish and so dizzy, so I sat down and let my students take the reins for the one class I’d planned to really aggressively conduct, because Cixous (who sometimes seems obvious) keeps changing like female pleasure under anyone’s finger — but my students, while I almost passed out, wrote a beautiful class.

With my cervix softened the IUD went in later that afternoon. It went in easily. It was fucking placed. Ta da! Boing! I thought about going home and just, fucking:

With Paragard®, you don’t have to worry about setting an alarm or remembering to visit the pharmacy. After Paragard® is in place, all you need to do is a simple monthly string check. It’s quick, and your healthcare provider can walk you through it the first time. Otherwise, Paragard® shouldn’t affect your day.

Six days more (there is night), I was back. I was sitting on the vinyl table in there dressed in paper, a dress, praying the doctor on call would remove my IUD. The nurse had said, as she took my vitals, “Maybe,” “If,” “We’ll see.” They would want to convince me to endure the initial bout of side effects — “Heavy bleeding, spotting after periods, and cramping” — and when the doctor finally came in the room and I wouldn’t listen and said, “Take it out, take it out,” coaching myself to sound better, measured, employed, but couldn’t, and when she finally did, she said, “What a waste.” She referred to the IUD, the 900 dollar device that I’d wasted in myself, but I was there — my heart palpitating, I can’t quite say it yet, my whole being fuming with poison — to take myself back. She was hard, annoyed, she had yanked it out of me roughly and showed it to me — the little cross, “Here it is, what a waste” — I was there to steal, to yank myself back.

I want to get to a proposition, but I will say, in the hospital elevator leaving without it, I cried and uttered, “It’s ok, it’s not in us,” which is to say that I was terribly emotional, and that I experience self as a flock, and that, with that little piece of copper in my uterus, I experienced great changes. I felt faint, rigorously depressed, migrainal, more paranoid than usual, implanted with the ghost of a sneering woman who spoke to us, and I smelled bad. Like a corpse. My “heavy bleeding” wasn’t menstruation, it was cut from the jugular of the Styx. I visited my sister and my new nephew — I held him like a jug of mildew. Affectless. Exhausted. I walked a copper life.

I don’t know why I didn’t consider the mysteriousness of all matter — of copper. What is copper? I only read the given literatures of this metal, the Paragard pamphlet, and a few online message boards and articles about the worthwhile travails of IUD insertion (Jezebel has some helpful tips) — because I wanted it, so badly, in me. I wanted my partner’s cum. I wanted to fuse a woman’s problem with its solution, to fuse myself with cum, with capital, become bionic, posthuman, or to at last become like a woman. “I’m an IUD lady!” I said so gleeful to people, to my partner, when the second try for insertion worked. How to read this sentence? I read it now, “IUD,” the alibi for “lady.” That unknowable, un-be-able sphynx. I’ve wanted her, too.

I wish I’d known, or rather thought about — read — copper. The pamphlet boasts that a copper IUD is not hormonal — but it is something. What? What is copper?

A prescribed bibliography is not enough, and it is women who more often are the receivers of a limited set of texts: think of the popular “gift-books” of the 1820’s, marketed for women and containing poetry of sickly sentiment and domestic concern, the “woman’s film” of the 1930’s, where proms, weddings, and births are represented in a dulling (naturalizing) repetition of the “mythemes of femininity,”[1] or today, any number of self-help books designed to help woman understand self as pathologically as possible to thus change this self and thus change life. Think of a million things.

Having a copper IUD implanted in my uterus was, for me, a big disaster. If it had stayed inside longer, perhaps for the nine years it is meant to rust and endure there, I would have lost great portions of my health, happiness, and relationships. But I don’t wish I had understood myself better. There is nothing to really understand there, no secrets. I wish to read copper, O mysterious material. And I think we need — especially women, or anyone oppressed, or prone to being handed texts that are limited to being for us and our purposes (“purposes” invent this “us”?) — to build messy bibliographies that can’t perceive limit.

“Write her self”: I want to read a thing — the copper IUD called Paragard — against the hard song of the sphinx, and I am building, in the aftermath of my copper insanity, a new Paragard library.

The library includes the archival material of Paragard’s own pamphlets, quoted above, and online material designed for women, an article in Jezebel titled “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love My IUD,” which celebrates, too, what copper isn’t, the hormones. What is it?

CAConrad writes about copper in one of his somatic poetry exercises, “Aphrodisios”:

Wash a penny, rinse it, slip it under your tongue, and walk out the door. Copper is the metal of Aphrodite, never ever forget this, never, don’t forget it, ever.

Copper, metal of the goddess of love, functions in the uterus as sperm killer. But like things, it does more. It mysteries. The somatic exercise changes registers; Conrad first asks his subject to meditate on love with copper in the mouth, but moves this penny to the top of her head, and changes the subject:

Be quiet while thinking about that Love. If someone comes along and starts talking, quietly shoo them away, you’re busy, you’re a poet with a penny in your mouth, idle chitchat is not your friend. Be quiet so quiet, let the very sounds of that Love be heard in your bones. After a little while take the penny out of your mouth and place it on the top of your head. Balance it there and sit still a little while, for you are now moving your own forces quietly about in your stillness. Now get your pen and paper and write about POVERTY, write line after line about starvation and deprivation from the voice of one who has been Loved in this world.

You attend to a thing by putting it in your mouth, and on your head—to taste, to balance, to put your body in the path of its force. You put your love, its great force, into the path of Poverty.

I began to read the new copper in my body, while the IUD was still in it. It could be read. I had become upset by something with my partner. It was something quite subtle — an affect, a line of discourse at a dinner party — and as I unpacked my upset, the upset kept growing worse, and strange. Its language — a few sentences — gummed my entire mind and I thought them, and said them, thought and said them, again and again, for hours, in the shower, in bed, in creepy whispers, out loud on an interminable wheel to my sister, these sentences — two, three — indissoluble, my mind was entirely made from them, and my heart was highly palpitating, and I felt anger and paranoia and depression and produced a new sentence, “I will punish him,” and with an oncoming migraine, and no affect, my nephew a mere jug, I decided — another new sentence! at least! — “I will kill myself.”

I typed into my computer “IUD copper and depression,” and it flooded with message boards and support groups full of thousands of women. An article titled “In Online Forums, Women Share IUD Fears” predicts me:

Many [women] are drawn to online forums after they search for a possible relationship between ‘copper IUD’ and ‘depression.’ Theories about copper toxicity are the first to pop up with a simple search on the Internet.

The Facebook group Paragard Don’t Get One has stories from its 5,500 members like this, from Ebony:

I had the Paragard inserted in Jan 2012. After having it put in, I cramped and spotted for a few days, nothing out of the normal. As the weeks and months went on, I never felt “well”. I could never pinpoint what was wrong, just didn’t feel well. After about 6 mths I started having terrible heart palpitations that got so bad, I went to the ER because at the time I thought I was having a heart attack. I also started to experience panic attacks & anxiety….I always felt like the worst was near. In August of last year I had it removed and I instantly started to feel better. Below is a pic of what it looked like on the day I had it removed. I only had in for 2 1/2 years, look how rusted it was.

Why would I want rusting metal in my uterus? You are supposed to get a tetanus shot if rusted metal is scraped across or makes an open wound. What is a uterus?

In the U.S., the only available copper-releasing IUD is called ParaGard and is produced by Teva Pharmaceuticals, an Israeli company that acquired the product in 2005.

I have been practicing BDS since the summer of 2014, when Israel’s “Operation Protective Edge” killed (according to the UN) 2,251 Gazan civilians; the Gaza Health Ministry reports that 578 of these were children. BDS — “The global movement for a campaign of Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel until it complies with international law and Palestinian rights” — had me disabling and trashing my SodaStream in July, and prevents me from buying Victoria’s Secret underpants. I had written a careful letter to my university’s reading series suggesting we no longer put Sabra Hummus ($2.98) on the food table. Imagine my horror when I found out what glowered, for $900, in my uterus.

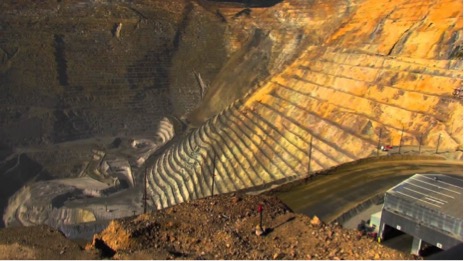

The glower of the copper holes of Utah, my recent home of four years, whose copper mines would fill my winters with a noxiously sweet smell I don’t know like the pussy of a car. These holes responsible for a third of Utah’s notoriously bad air quality, people in winter wearing fibrous high-tech masks, and I could see such fumes sometimes from my canyon’s rim, to the right of the lake, copper was maybe on fire.

In October of 2014, Noam Chomsky spoke at the UN:

Last August, August 26th, a ceasefire was reached between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. And the question on all our minds is: What are the prospects for the future? Well, one reasonable way to try to answer that question is to look at the record. And here, too, there is a definite pattern: A ceasefire is reached; Israel disregards it and continues its steady assault on Gaza, including continued siege, intermittent acts of violence, more settlement and development projects, often violence in the West Bank; Hamas observes the ceasefire, as Israel officially recognizes, until some Israeli escalation elicits a Hamas response, which leads to another exercise of “mowing the lawn,” in Israeli parlance, each episode more fierce and destructive than the last.

“Transpierce the mountains instead of scaling them, excavate the land instead of striating it, bore holes in space instead of keeping it smooth, turn the earth into swiss cheese,” is how the philosophy duo Deleuze and Guattari talk of mining the earth for metal, an anti-agriculture. Antivegetal, in-vegetable, the flow of matter is essentially metallurgical:

In metallurgy, the operations are always astride the thresholds, so that an energetic materiality overspills the prepared matter, and a qualitative deformation or transformation overspills the form.

Uncontained, or the container, it fumes, dislocating, vague and pervasive, a dis-place, metal for D & G is a “destratified, deterritorialized matter”: “Metal is neither a thing nor an organism, but a body without organs.” It “enters assemblages [like a Paragard?] and leaves them.” D & G unmetaphor metal and roam in purest haecceities — in Latin “thisness,” the characteristics of a thing that would make it such — touching at metal/metallurgies like a Cixousian clitoris, prolonging a production of forms:

Metallurgy is the consciousness or thought of the matter-flow, and metal the correlate of this consciousness. As expressed in panmetallism, metal is coextensive to the whole of matter, and the whole of matter to metallurgy. Even the waters, the grasses and varieties of wood, the animals are populated by salts or mineral elements. Not everything is metal, but metal is everywhere. Metal is the conductor of all matter.

And thought is born more from metal than from stone.

“The medical profession is never, ever going to be interested in [copper toxicity] because there’s no drug that you can use (to cure it),” says Theresa Vernon, a nutrition consultant quoted in the article I had found.

The internet pulses, heavy-ing, with Cassandras. A contributor to the group copperiuddetox has only been able to confer the seriousness of this matter with other sufferers (940 in this group) of its force:

I know exactly what you mean about the copper being related to the myriad of symptoms / health issues… Sometimes my fiancé looks at me like “are you really going to blame copper on THIS too!” But I’m not kidding … My entire life has been effected… And YES I DO blame this F’n IUD for it because it was the only thing that changed in my life and this is no coincidence. It’s just ridiculous. Feeling paranoid about everything and it’s really taken a toll on my self esteem which greatly effects all areas of my life. I, too, was crying yesterday… And do often. I just feel exhausted and overwhelmed by all this and the NOT knowing exactly what to do to fix all this is the worst part … It feels like some days I’m just standing here watching myself in total chaos feeling like death and looking like it too and I feel helpless.

Many women in copperiuddetox had their IUD for years. Mine was in for 6 days. I try to read it in me still, a pyrite tailing of what happened. Sometimes I feel the way copper tilts in me now, the tip of too much metal. A flash of new, uncharacteristic, acne — a new, sick sentence that begins in me to make its mouth. I was always walking a copper life, now I am sensitive to the delicacy of the narrows of this path. Many of the IUD’s effects have lifted, or can no longer be read. And I fuck my partner with condoms. I say, while fucking, “I want your cum.” I fucking beg for cum. I don’t mean it. Words don’t mean, or they are metallurgical, they fume from their beautiful assemblages. There is pleasure in not meaning anything, not even what I want. What I say, while we fuck, splits from what is, will, or can happen. Pleasure floods unmitigated into this space. Words can’t mean, it’s why I want so much.

[1] Mary Anne Doane’s phrasing in her essay on the woman’s film, “The Desire to Desire” (1987).

Caren Beilin is the author of a novel, The University of Pennsylvania, a memoir, Spain, and Blackfishing the IUD. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in the Berkshires.

This post may contain affiliate links.