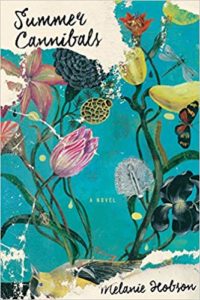

[Grove Press; 2018]

[Grove Press; 2018]

In the classic novels of waning patrimony — Brideshead Revisited, The Sound and the Fury, Lie Down in Darkness, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle — the impacted spoils of privilege spell the undoing of proud names and palatial estates. With time’s groaning passage, buried antipathies turn prominent families into feral village pariahs. The absence of a suitable heir, whether in the bloodline or in wider modernity, strands reclusive specters drifting through abandoned manses. Luxuriant demesnes go back to nature in the wake of suspicious bigotry and protective denial.

Summer Cannibals, Melanie Hobson’s addition to the canon of Country Manors In Sharp Decline, proposes another reason for the downfall of polite society: the patriarchy itself. During a tense reunion at their parents’ lakeside Hamilton mansion, three virtually estranged adult sisters revisit the scenes of their youth and the domineering male influences which dictated their childhood traumas. Bordering on caricature, Hobson paints an Ontarian hellscape of rape culture, suggesting that the defensive malice of the elders in Waugh, Faulkner, and Styron’s novels might be more succinctly encapsulated in the simpler concept of toxic masculinity.

The Blackford sisters are, tellingly, each named for men, and even amidst their far-flung adulthoods evince a fierce competitiveness inherited from their squabbling parents. The reunion coalesces around Pippa, the youngest, who’s retreated home from the South Pacific in the late stages of her fifth pregnancy. Ex-party girl Jax is floundering in the doldrums of middle age and an unhappy Florida marriage while Georgina, the eldest, has undertaken a quiet career in local academia.

The old house on the lake proves an inopportune haven for pregnant Pippa because their father David, a ferocious gardener, has planned a civilian tour of his immaculately maintained grounds. “Life, he often thought, was a never-ending fight for virility,” David declares to himself during an introductory monologue. In the lead-up to the tour, the strain of David’s relationship with his wife Margaret manifests in petty aggression and, eventually, physical violence. Packed into a home with four women and facing the slow erosion of white male privilege, he asserts his diminishing position through his long-standing practice of beating and raping his wife.

The garden tour is his latest obsession for the opportunity it poses to preen his feathers before the uncultured masses. But once the philistines arrive at the gate, it’s clear he’s made a fatal error, cheapening the ancestral terrain by turning it into a tourist attraction. As hosts the Blackfords — even Margaret and the girls, who are indifferent to the whole endeavor — are reduced to groveling before vulgar gawkers, waiting on hand and foot as the daytrippers trample David’s meticulously cultivated plots. Craving the approval of his neighbors, David realizes his miscalculation once he beholds the boorish hobbyists running amok on his property. He is lost and besieged when the greater world impinges upon his walls.

Summer Cannibals’s sluggish first half is all foreboding, a protracted redrawing of territories and alliances among the Blackford clan. They bicker over fruitcake and air conditioners, goading one another with a malicious, desperate intensity. David and Margaret’s discord is described: “At times like this, they knew from experience, those grievances would overwhelm if given half a chance and neither of them could afford that because each had their hobby horse to ride, and neither wanted to surrender the lead — because each felt they had the upper hand.” While David is an abusive monster, Margaret is herself a manipulative ghoul, her feminine cunning a propeller of the family’s turbulence as she resumes control of her daughters’ schedules and emotions. Hobson empowers Margaret as a witchy femme fatale, but her supposed villainy at the expense of her daughters is hardly tantamount to David’s unconflicted savagery and egotism. Casting her manipulation as a counterweight to David’s depravity has the unfortunate effect of conflating a vengeful woman with a hysterical rapist. David’s violence is alluded to but mostly occurs offscreen, at best minimizing it and at worst imbuing it with an inconsonant Fifty Shades kink.

The disastrous garden tour upends their uneasy balance, exposing each of the Blackfords’ vicious appetites. It’s also the point where Hobson shifts from listless domestic drama to outrageous fairy tale. After spying a couple copulating in a grove during the garden tour, David and Margaret take the young woman prisoner and, together, make her their sex slave. It’s later revealed that she’s a prostitute, and, even more incredibly, she somehow accepts her imprisonment. The painstakingly developed tone of the novel’s first half is undone as the Blackford hierarchy is reset by the introduction of a concubine. Yet through all this the sisters proceed with their limp, wayward homecomings, despairing over their comparably civil marriages and reminiscing on teenage flings.

The sisters are intended as the most, if only, sympathetic characters, but their mopey self-examinations border on absurdity as David passes days raping his wife and prisoner behind closed doors. While aware of his cruelty the sisters are oddly dismissive of it, in the same way they’re resigned to their mother’s importunate qualities. Georgina and Margaret’s characterization predicated on their devotion to art is flat, whereas Jax’s as an aspiring playwright who neither watches nor reads plays is hasty and dubious. The sisters’ unfulfilling marriages are insufficiently distinctive, and while the narrative might easily have sustained a single daughter or two sisters, it is overladen with three separate subplots.

Hobson is most impressive when her omniscient narrator executes naturalist depiction, tacitly suggesting that the domestic atrocities of Summer Cannibals are another function of brutal biologies. Driving into town Georgina notes that “The black maples and sumac and birch on either side of the narrow road taking her down the escarpment had the weary August appearance of leaves that have taken on too much.” Meeting her extremely pregnant sister at the airport,

It was as if her actions and thoughts were slowed down to the tempo of something as primordial as one revolution of the sun and the moon. She seemed tidal. In motion, but deceptively so. You’d have to close your eyes for an hour and reopen them to notice a change, and even then it would be so slight you wouldn’t be sure it was true.

During the garden tour, Pippa observes an unruly group of guests invading the swimming pool:

She watched as the four at the edge turned, in unison, and began pulling themselves hand over hand around the edge and back to the steps and out, like flotsam being pushed by this rogue tide that had risen from god knows where with a pull stronger than the sum of them.

Yet this also serves to rob Hobson’s characters of agency, rendering their lascivious impulses as primal and even normal. The exception is an internal monologue in which Pippa considers her role and experience as a mother, featuring some of Hobson’s sharpest insights:

It had been a continuous twenty-four hour cycle of loving and hugging and nocturnal shifts into their parents’ bed until by morning the whole family was draped across each other like a heap of laundry, their bedroom a den. She’d set out to construct a utopia of wonder and amazement, populated by little foot soldiers of joy who would go out into the world and cast their joy around — a storybook on homemade paper, written in vegetable dyes and drawn with love, where the words were symbols so anyone could understand. . .But what she’d gotten were junkyard dogs. Scrappy animals. A howling mess.

Of course, these pearls are subdued by their encasement in a rape-centric fairy tale, one reliant on heavy-handed imagery such as a lawn statue of Aphrodite and a predatory character who introduces himself as Lucifer. Even with its ridiculous S&M politics, Summer Cannibals is governed by such a straight-faced sensibility that it’s a rather humorless affair.

As the narrative approaches its surprising climax — no small feat given the mounting absurdities — the exposition is contingent upon a glimmer of hope that David, an incorrigible rapist and bigot, might be somehow redeemable. As victims Margaret and their prisoner are conveyed as far from blameless, and their continued tussles dull the misdeeds of a character far too vile for absolution.

With its timely satire of sex and manners, Summer Cannibals inverts the beach read by promising a lusty domestic romp which in fact houses something much darker. But its brutality and antipathetic characters result in foggy resolutions. Margaret derives a sly, vindictive power from her femininity, but this also makes her seem like a witch; after capturing her winsome young prisoner in the tower like a streetwalking Rapunzel, Margaret drugs her to indulge in her adolescent beauty. If marriage is an outdated, misogynist institution, it is, via Hobson, still inevitable. The author’s ambivalence toward marriage is captured in the way Jax and Pippa effectively cancel each other out: upon the birth of her daughter Pippa declares that her days as a swinger are over, whereas Jax ultimately decides that the way to fix her quiet domestic life is to embrace promiscuity in middle age. Even the nuclear family is presented as a necessary evil, a vehicle for self-determining units to claw for rabid footholds upon one another.

As broadstroke commentary on the nature of patriarchy, however, Hobson’s debut is by turns riveting and resonant. In contrasting a light patrician tone with bloody assaults, she proposes that houses of splendor are built upon inequality and submission, that the leisure class is founded on individual misery, and that even if society’s old money influence is subsiding, its history of rape and plunder is stifling. As in any worthwhile battle of the sexes, the men of Summer Cannibals have underestimated their opponents, but it’s not a satisfying outcome for either side.

Pete Tosiello‘s literary criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, The Village Voice, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. His music writing has appeared in SPIN, Vice, Forbes, and The Atlantic. He lives in New York City and works in technology

This post may contain affiliate links.