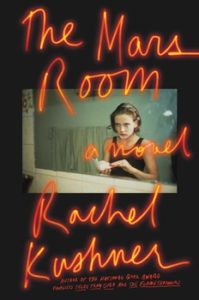

Rachel Kushner’s first two novels — Telex from Cuba and The Flamethrowers — were worthy finalists for the National Book Award. Given the enthusiastic pre-publication reviews of The Mars Room and its intense empathy for female victims of poverty and of the penile/penal system, the novel looks like an early favorite for an award, maybe the Pulitzer this time around.

One of our smartest and most adventurous younger novelists, Kushner belongs to the Nan Graham school of fiction. Graham, the Vice President and Publisher of Scribner’s, edits Don DeLillo, who has been cited as an influence by Kushner and Dana Spiotta, both of whom Graham has also edited. What the three have in common is their approach to fiction as cultural anthropology, a form for exploring the intersections of mysterious private needs, rituals of popular media, micro social systems, and global politics. Underworld is the grand exemplar. Telex from Cuba and The Flamethrowers have some of that novel’s historical and international breadth, plots against traditional power structures, and a mix of underground characters and “real” people, along with DeLillo’s methods of formal collage, multiple points of view, alternating styles, and authorial neutrality. Telex from Cuba is about Americans in that country during Castro’s revolution. The Flamethrowers moves its American protagonist from aesthetic radicalism in 1970s New York City to political radicalism in late 70s Italy. Even when the characters in these novels are not intellectuals, one senses that they emerge from a long and rigorous intellectual — anthropological — engagement of Kushner with her settings. “What to think?” one thinks when finishing the books.

The Mars Room also has an “exotic” setting but is more limited in its scope and more visceral in its effect. Most of the novel takes place over four years early this century in a California prison for women that Kushner calls Stanville. An inmate refers to “mass incarceration,” but The Mars Room isn’t really about that because most of its characters are guilty of major, violent felonies, not minor drug offenses. About two-thirds of the novel is narrated by Romy Hall, who is 29 when she begins serving two life sentences for murder. Another substantial portion is told through the eyes and mind of Gordon Hauser, a young teacher in the prison who befriends Romy, sends her books, and smuggles her contraband. A crooked male cop, a lifer in another prison, has his story told, as does the man whom Romy killed. Though the three men are presented in the third person, Kushner gives them as much interiority as her first-person protagonist.

Even an anthropological novelist needs plot, and Kushner has three — the backwards revelations of why Romy killed, the present possibility of a romance with Hauser, and the future potential of an escape. But the novel’s primary appeal — and it is very powerful for someone who has seen only one episode of Orange Is the New Black — is Romy’s inside observations of the prison, its physical spaces and procedures, the other inmates, and the guards. In a remarkably forthright interview with Deborah Treisman for a New Yorker blog, Kushner discusses the years of research she did for the novel and calls some of the inmates she met her “friends.” Romy and the other prisoners do not consider interested outsiders such as Kushner as “friends,” only as potential “victims,” what they call “runners” who may be cajoled or seduced into doing something for inmates. Reading Kushner’s interview, I wondered — as I did when reading The Mars Room — if she had gotten too close to her characters, if she created them without the kind of objectivity that would ask readers to think about them rather than feel for them as visitors might for friends. Since “feeling” has increasingly become the quality prize juries reward, Kushner’s shift toward the solicitation of intense emotional response is probably a good career move.

There is a “thinker” in The Mars Room. Hauser, a failed graduate student in literature, lives in a mountain cabin far above the Central Valley prison and, like Thoreau (who is quoted) and the Unabomber (whose diary passages are inserted every 50 or so pages), Hauser bemoans the industrialization of nature — the mechanized routines of the prison and the large-scale farming of the land. In case we don’t understand the negative influences of the characters’ backgrounds from their anecdotes and stories, Hauser points out that most of the inmates were shunted toward crime by family abuse, poverty, race, ethnicity, drug abuse, mental illness, and other fateful circumstances. Hauser ultimately becomes a “runner” who helps, unwittingly, a woman on death row put out a contract on the crooked cop and who gives Romy the tools of escape. Kushner incorporates the literary Hauser for an external perspective on Stanville, but here’s another thing I wonder: does Kushner recognize that her book may make her a figurative “runner” serving her imprisoned new “friends”?

Romy Hall is a compendium of pathologies: no father, an alcoholic and indifferent mother, sexual abuse as a child, early drinking and heroin use, petty crime, no possibility of college, sex work at the club called the Mars Room, an unplanned pregnancy, bad “luck” with men, and inability to escape the past. But she remains a plucky heroine, insisting on her dignity even in the ugliest circumstances. She moves from San Francisco, where she lived into her twenties, and begins to have a new life with her seven-year-old son in Los Angeles. But one of her former lap-dance customers at the Mars Room, who stalked her in San Francisco, shows up on her porch. Unable to stand without canes because of a motorcycle accident, the stalker is physically unthreatening, but Romy may not know this — just as she doesn’t know a lot of things outside of her demimonde existence. She clubs him with a tire iron, a murder just about as irrational as the shooting at the center of Underworld and as unpremeditated as Raskolnikov’s second murder in Crime and Punishment, to which Kushner refers. In prison, Romy says, rather vaguely, that “pressures” in her life built up and she acted on “instinct.” Her sentences she blames on an incompetent public defender. Although this rationalization and Romy’s violent act revealed near the end of the novel may unexpectedly modulate a wholly sympathetic response to her, Kushner closes with Romy’s lyrical epiphany in a natural setting (I’m being intentionally vague here) that may allow readers to leave The Mars Room with a good feeling.

Romy and other inmates say prisoners always lie, but Kushner seems to present her as a reliable first-person narrator, one with whom readers are encouraged — sometimes by use of the second-person — to empathize without questioning her story. A more thought-provoking way of investigating the relation between a prisoner and the outside world (including readers) can be found in Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace where Grace the convicted murderess may use her “feminine wiles” to manipulate a “sensitive” character like Hauser and others. Atwood’s readers are uncertain about Grace’s character, guilt, and rehabilitation — and what those words might mean. There’s little space for this kind of ambiguity in The Mars Room. Yes, it is a fiction, and some of its devices — such as metafictional references and multiple viewpoints — remind readers of that fictionality, and yet it appears that Kushner wants readers to believe — and feel — that the book is transparent, almost literally true.

Most of the inmates of Stanville admit they are guilty of felonies. I think that Kushner is also guilty — of an aesthetic misdemeanor, earnest sentimentality. She includes numerous references to country music, simple songs about intimate tragedies of love and violence. She also alludes to Steinbeck, though not to Grapes of Wrath, which ended in California farming country. Accused of sentimentality for his ending of that novel, Steinbeck traced long and complex chains of causality to elicit empathy for his Joads. The Mars Room is more like a country music album than a naturalistic novel as Romy and the characters recorded by her tell their sad stories in capsule form and vernacular language. As in some country music, the city is blamed for unhappiness. For Romy, the Mars Room represents the “curse” of San Francisco. For the mountain-dwelling Hauser, Stanville (a word that combines the Hindi for “place” or “home” with “ville”) is a city of the plain. In this novel that ends in a redwood forest, the pastoral is one more component of Kushner’s appeal to sentiment. As is the situation of Romy’s son, Jackson. After Romy’s arrest, he is taken in by her mother, whom Kushner kills off in an auto accident, leaving Jackson a ward of the state, Romy desperate to get out of Stanville, and Kushner desperate to help her with some implausible plotting. Like that American classic of sentimentality Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Mars Room takes its title from a closed space of exploitation, but Kushner’s novel has nothing like the cultural range or moral authority of Stowe’s.

Among the books that Romy and Hauser discuss is Charles Willeford’s noir novel of San Francisco Pick-Up. Romy says “it was good and bad at the same time.” Houser replies, “I know what you mean. The end is ridiculous, right? But it makes you want to reread the book.” I might have been more impressed by The Mars Room had I refrained, but rereading this novel was just not as rewarding as, for example, my second reading of The Flamethrowers. When fewer and fewer people are reading literary fiction for a first time, perhaps this second-reading criterion is a pathetic holdover from a bygone age. But I think rereading is still a useful way to judge, once the flame has been thrown, if there’s anything left to think about.

Tom LeClair is the author of three critical books, six novels, and hundreds of reviews and essays in national periodicals.

This post may contain affiliate links.