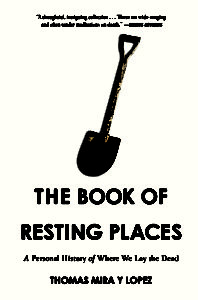

Thomas Mira y Lopez’s The Book of Resting Places is a monumental collection, if only because the essays in this first book examine so many of the grand structures humans have assembled throughout history to house and commemorate the dead – pyramids, vast networks of catacombs and cemeteries, looming obelisks, empyreal arbores. In addition to this architectural legacy, the book also draws on the literary heritage of death with unassuming erudition. Rarely have Virgil, Dante, and Hans-Georg Gadamer sounded so conversational. Up against this heft of tradition, the present can seem small. But even when Mira y Lopez dips journalistically into some of the curious morbid practices in our current age – tempered in his record by the personal struggle to grasp his father’s death – he encounters a tension between body and essence, a tension that has been preserved in our discourse much longer than our bodies ever will.

A pilgrimage to Alcor’s cryonics lab in Arizona provokes this tension, as the sensible author and his girlfriend get a freakshow tour of every appliance and extreme measure in force to keep dead bodies and dismembered heads from further degeneration. Setting aside the debate over how likely it is in the medically-advanced future to thaw out the bodies and bring them back to working order, Mira y Lopez is struck by the indignity of keeping a body going beyond some kind of natural threshold. In his caring tribute to his father, he also wrestles with the ambiguity of this threshold, the natural time to go, and for loved ones to let go, against an “unnatural” macabre delay. “What seemed not just surreal but downright unnatural,” he writes in “The Eternal Comeback,”

was that I believed I was going to a place that ran counter to the human body’s most natural instinct. I thought of my father and his seizures, his craniectomy, and how when a quarter of his skull was removed, his brain seemed to breathe of its own accord. I thought of how his body was sending a message, however much I didn’t want it to, that it bore intolerable pain and wanted to rest. I thought how life meant death: that this was what we’ve been told everywhere, all the time, as long as we’ve been alive. How then did a group of people convince itself so thoroughly of the opposite?

A conventional piece of feature writing would end it there, choosing its side and ridiculing the opposing subculture through a series of superficial gross-outs. But here, this is only the beginning of an essay that dives head-first into the futuristic crypt to a depth of genuine curiosity and soul-searching, striving to decode the hidden values behind an unknowable opposition. The virtue upheld by cryonics supporters is that although much of their high-tech practice is rooted in their blind faith in the future, this faith is a wager on human progress. Their hearts are in the right place, and yet the “totem pole” of heads crammed into a single pod symbolizes some kind of essential violation the author can’t ignore. “It wasn’t exactly the viscera that unnerved me, or the body’s desecration,” he reasons. “Instead it was the sense of hope that threw me off, the violence that accompanied such wishful thinking.”

There is an unavoidable politics of death that marks this collection like so many headstones. How societies treat their dead says a lot about their management of the living. This continuity manifests at the personal level in the opening essay, “Memory, Memorial,” which plants associations between parallel fragments about the illness and death of Mira y Lopez’s father, Rafael, the mythical river Lethe and about the buckeye planted by Rafael before his death, on the grounds of the family’s second home in Pennsylvania. This essayistic impulse to forge continuity extends across the country in several essays, and it manifests globally when Mira y Lopez writes about experiences abroad in Venice and Rome.

“Overburden” follows Mira y Lopez from the Manhattan haunts of his youth to Tucson, Arizona, where his assumptions about the eternal safeguarding of sacred burial grounds is rudely laid to rest. Old favorite restaurants and video stores die, but cemeteries live forever. Or do they? When Pima County inspects the site for a new courthouse, they discover an unmarked cemetery. Retracing the history of Tucson through this site, and researching some of the 1,300 human remains buried there, Mira y Lopez turns investigative reporter, gaining access to the site and unearthing the reality that even permanent resting places are in flux, whether through old land acquisitions or more recent city planning. In the ongoing struggle between the dead and the living, the local burial grounds are like “a grandparent who has you by the ear,” our underworld cicerone intones. “A cemetery,” he continues,

needs an audience to pass along its memories of a city’s past occupants, yet it’s also there to send a message, a basic inevitable truth: a city of the living one day turns into a city of the dead. Though we all die, with the proper record-keeping and a bit of endowment, we might not all be forgotten.

So much of what delights in this collection goes beyond official documents and authorized histories. At the same time, facts and fact-finding shape several essays. One in particular, “Parallax,” begins almost like a grade school science report, so fascinated it is by Galileo’s study of sunspots. This leads to Mira y Lopez recalling the sunspots on his father’s skin, a kind of skin he also has, this organic connection with his father. Unlike cold hard facts, people from Mira y Lopez’s past are subject to change and vanish. At age twenty, his life is upended by his father’s passing, yet by reflecting on this change, his understanding about memory – the life-source of essays – evolves to recognize the importance of place, which makes this loving tribute also an impressive collection of travel writing. “By staking memory to a place,” states the author, “we absolve ourselves its full weight; the bookmark replaces the finger that might have been kept on the page.” In the case of Paulo, a somber host while visiting Rome, the experience of exploring the catacombs is indistinguishable from memories of the hardworking person who shared quiet dinners with Mira y Lopez. Years later, this same Paulo can’t be found on any social media search, and so has met a kind of death.

Mira y Lopez’s encyclopedic interests flirt with the ready information saturation of the current moment, but his facile movement between subjects, both cerebral and intimate, honor the careful attention of authorship over hiveminded wikis. The book’s subtitle, “A Personal History of Where We Lay the Dead,” makes clear the autobiographical cohesion of the project, and moves beyond formal anxieties about the classification of longer works, be they novels, novels-in-stories, or, in this case, a memoir-in-essays. The development of characters, though ostensibly true to life, impart a crafted, though genuine-seeming, novelistic build. The reader comes to know several of these people quite well, or aspects of them, putting into practice what Mira y Lopez has learned about the impossibility of remembering another, even his father, in a comprehensive way that satisfies his encyclopedic desire. Knowing the history of a place, or a person, isn’t the same as spending time with that same person.

All these merely formal and epistemological dissonances culminate in a masterful tale, “The Rock Shop,” set in Old Tucson. The survival of a creepy curiosity shop in the iPhone era makes an unlikely hero of its “telluric” proprietor, Roger. In this piece, Mira y Lopez trades the digressive animus of Melville for truly Poe-like arabesques. The kind shopkeeper invites the visitor and his mother to see an ancient mummy Roger “inherited” from an Egyptologist (every gladiator’s skull and mummified pack rat has a story behind it), but the real horror surfaces, in a contemporary twist, when we read Roger’s hateful messages on Facebook. But the tangential quality of this climax calls attention back to the journey, the campy benediction over a 3,500-year-old mummy named Heck, hiding in the American Southwest next to a teepee once inhabited by Geronimo’s supposed grandson. In this scene, as elsewhere in the book, Mira y Lopez’s mother, Judy, brings her funny blend of superstition and portent. Objecting when her son rubs the mummy’s head, she punches him in the arm.

For all the studied excavations bound up in The Book of Resting Places, the people remembered in its pages, those passed and still with us, remain glowing torchbearers for the living.

Christopher Wood is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, who now lives on Long Island.

This post may contain affiliate links.