[Nightboat Books, 2023]

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, I wrote a memoir. Like many others, I found myself underemployed, holed up at home with no children, and free to write. At first, I wrote to snuff my restlessness. I craved control. I sat at my desk and scribbled essays about pack rats, Covid, and the city’s housing crisis. I was grieving the loss of my pre-pandemic life but also processing the traumatic relationship and domestic situation I had fled days after California issued its first Stay At Home Order. I wrote to make sense of both the immense loss and the newfound joy I felt every day. This novel pleasure pulsed alongside daily reminders of sickness, death, and misinformation. I wrote on, through summer and into winter. In Spring, when I returned to in-person work, I abandoned the manuscript.

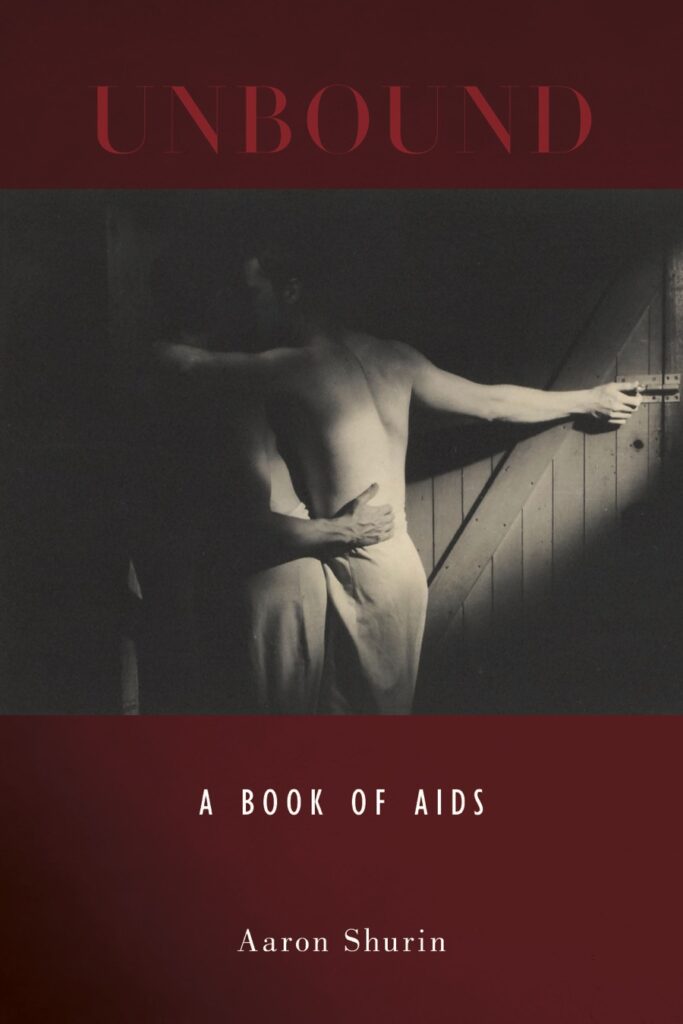

The project was finished. I stuck to this story. When I revisited the manuscript in early 2023, I found it lacking. Specifically, I was shocked by how little I wrote about the pandemic even as I was living within it. This was especially surprising considering my memoir is in the style of a daybook. I set out to expand the work, forcing myself to linger within those early days of the pandemic. Yet, whenever I sat at my desk, I struggled to accurately capture the pandemic’s horror, mundanity, and drama of waiting for test results. I couldn’t find a way back in, not until I read poet Aaron Shurin’s Unbound: A Book of AIDS, originally published in 1997 and recently reissued by Nightboat Books. Intimate and rangy, Unbound’s sixteen essays offer not only a nuanced portrait of the AIDS era but also a priceless guide for how to write about catastrophic collective and personal loss.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the loss Unbound charts is its ongoingness. The enduring nature of this loss is reinforced by the book’s chronological structure, which features essays written between 1985 and 1997, as well as a new forward that situates the book within the current ongoing COVID-19 moment. “As the COVID-19 pandemic rages around us,” Shurin writes in the forward, “how could I not recall that other epidemic, unrelenting, ferocious.” To underscore the ferocity of the AIDS era, Shruin cites a 2018 statistic: 700,000 people have died of AIDS in the United States since the beginning of the epidemic. This is the only statistic in the book. Shurin otherwise eschews hard facts in favor of intimate data: personal reportage, gossip, and snatches of conversation between lovers and friends.

Each essay offers an intimate glimpse into the daily experience of AIDS, where sharing a joint and a piece of berry cobbler with a sick friend at a BBQ is as important a detail to report as the number of occupied hospital beds. Statistics, and other big-picture takes on human tragedies, powerfully capture the scope of loss, but Unbound aims for more. Shurin places us on couches, in hospital beds, and on the foggy streets of San Francisco so that we may not only know the scale of the tragedy of AIDS but also feel it. Shurin’s essays break through the haze of information: People who are loved, and are loving, perished. Every single life mattered.

Shurin gifts us with detail, the zoomed-in moment where we’re allowed to see an individual’s life in full color, with all its complexities. In Unbound, Shurin explodes the binary between living and dying. In “Notes from Underground,” Shurin shows us how his friends lived even as they were dying. “Some men I’ve seen . . . live sharper, richer, after diagnosis, become bigger, more generous . . . as they become thinner and weaker,” he writes. Consider Eric, a friend of a friend to whom Shurin only grew close in the last months of Eric’s life. “A possessor of erotic power most of his life, [Eric] never let go of it,” Shurin writes. “His body never became an ugly thing, though he was radically disfigured. His desire to charm outpointed his powerful adversary.” Together, Eric and Shurin pass through afternoons laughing, listening to show tunes, and feeding themselves with “holy dish.” To properly gossip, you must care deeply about other people—their desires, opinions, and decisions. One cannot dish alone. It’s Eric’s deep investment in his social connections and his ultimate desire to give and receive social pleasures that renders him “erotic” and “beautiful,” even as his physical body wastes away.

In Unbound’s world, caretaking is not a selfless act. Rather, caretakers gain great insight into the experience of dying and living. In Shurin’s hands, caretaking is a site of empowerment. “The server and the served were connected by a line of interdependence that constitutes a meaningful act,” Shurin tell us. “By turning the occasion away from illness and towards sociability, [Eric] located himself as a giver as well as a taker—a liver instead of a die-er.” Here, Shurin spotlights the inherent interconnectedness of all people and redefines what it means to be alive. It is our desire to connect with other sentient beings that give us life.

As the epidemic rages on, Shurin finds himself mourning not just the loss of close friends and acquaintances but also strangers, the nameless faces he once passed on the street. In “Some Hauntings,” he describes the bewildering experience of walking through the city hallucinating the faces and bodies of those who have passed. “These visions are gone in the next shift of wind,” he tells us. “[But] too late, for me, who has been struck by recognition.” He is haunted by these visions even as he no longer fears their appearance. He’s already confronted his fear of the impossible. As he reminds us, the impossible is already happening. How does one limn inconceivable loss? When implausibility gives way to brutal possibility.

In the essay “Inscribing AIDS: A Reflexive Poetics,” Shurin confronts the limits of poetry to address the rupture of AIDS. “By the time, the early 80s,” Shurin writes, “[when] AIDS began to claim unavoidably my most attention, the poem was emerging as an explorative maneuver, and the idea of thematic writing had become problematic.” The movement of poetry toward semiotics and conceptualism presented a challenge: how to write about the very literal theme of AIDS as a poet?

As Shurin reminds us, AIDS found him. “Meaning may be delivered,” he says, “bouquet or bomb—head on.” AIDS forced him to learn a new vocabulary; a vocabulary that called for a new language, a new approach. Shurin turned towards the essay, a generous form that allowed him to include ephemera, intimate letters, dance-texts, literary criticism, poetry, and more. “It was as if every valence in life were commandeered by the virus,” Shurin writes. “One needed every form of literary address to meet it.”

As a writer, Shurin can’t escape his impulse to sense-make through language. Metaphors seek him out and announce themselves. In “Generation,” one of the book’s most moving essays, Shurin walks through the Golden Gate Park after a destructive wind storm. A mess of snapped cypresses and other trees lines the pathways. He feels a tinge of sadness at the sight of so many felled beauties. As he walks on, he notices that the fallen trees have created a new refuge for the park where many birds that now make their homes among the wreckage. The birds are not the only benefactors of the newfound mess. This particular stretch of public land was once a popular cruising spot due to the coverage its overgrowth offered. Shurin tells us that a team of park rangers cleared the area in the early days of AIDS. Yet, the storm, and its destruction, redefined the space yet again, offering lovers a new-old place to play.

Through each essay, Shurin skins his sense of loss to show us the nerves twitching below. In Unbound, loss isn’t a static state but is always already dynamic. Life springs forth from the detritus of our losses. Shurin may not have wanted to spend years of his life writing about death, public health, and grief, but this is his world. In Unbound, there is no separation between our embodied life and our art practice. There is no pure form of art that isn’t touched by the historical moment that produces it. “Virus is also a form of life,” Shurin writes in one of the last essays in Unbound. “Its dogged contentions are inescapably creative . . . it’s writing me.” One of Unbound’s great offerings is its unsentimental recognition of the generative power of loss to write us as we write it. In the weeks after reading Shurin’s essays, I renegotiated my own approach to writing about COVID-19, and in turn, the abusive relationship I was lucky enough to escape during lockdown. I now understood I couldn’t explore one without exploring the other. Unbound gave me a way back into my work. Unbound let the light in.

Elizabeth Hall is the author of the book I HAVE DEVOTED MY LIFE TO THE CLITORIS, a Lambda Literary Award finalist. You can find her on instagram at @badmoodbaby

This post may contain affiliate links.