There are many versions of epistemology’s Gettier problem, but the one Edmund Gettier first presented describes two men, Smith and Jones, applying for a job. Smith has counted the coins in Jones’s pocket, and knows there are 10 of them. He also has good reason to believe that Jones will get the job—but actually, Smith is the one who will get the job. He also happens to have 10 coins in his pocket. Smith has a justified true belief that the person who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket at that moment, but it doesn’t feel like a case of knowledge to most people.

There are many versions of epistemology’s Gettier problem, but the one Edmund Gettier first presented describes two men, Smith and Jones, applying for a job. Smith has counted the coins in Jones’s pocket, and knows there are 10 of them. He also has good reason to believe that Jones will get the job—but actually, Smith is the one who will get the job. He also happens to have 10 coins in his pocket. Smith has a justified true belief that the person who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket at that moment, but it doesn’t feel like a case of knowledge to most people.

Gettier problems always have a structural “but actually” part when it turns out the sheep is actually a dog, the clock is actually broken, there are actually false Potemkin barns in this country—the “but actually” refers to a source of truth beyond what the character has access to. The source of this truth is the omniscient narrator. The narrator knows who is getting the job, and can say with absolute authority how many coins everyone has in his pockets. Smith has to judge whether his beliefs are sufficiently justified, but the narrator has direct access to the truth.

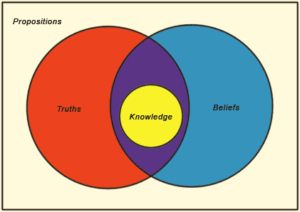

When Gettier first presented his paper in 1963, these examples seemed to many philosophers to complicate or refute the idea that knowledge could be defined as “justified true belief.” Most of the efforts to repair the study of knowledge attempted to fix Smith’s side of the equation, adding provisions about luck, or throwing out the source of our discomfort with these Gettier problems as only intuition about the nature of knowledge, which seems like a flimsy thing to question.

We shouldn’t be pressing on Smith, though—the reason Gettier problems feel tricky is the omniscient narrator that tells us what’s actually going on. This category of thought experiment can’t give us any insight into the nature of knowledge because we don’t have omniscient narrators in reality. We apply the word “knowledge” in circumstances with no equivalent source of absolute truth. The omniscient narrator is essentially supernatural, a source of information that has no real-world antecedent—in reality even divine revelations are not considered universally trustworthy. Gettier is putting his thumb on the scale of the exact quantity he’s supposedly measuring by giving us parallel tracks of information about the job and the coins, one that has to be justified and another that does not. It’s not a problem of luck or intuition; it’s a problem of examining Smith’s justifications for his true belief and not the narrator’s.

If we took out this omniscient narrator and re-described the Smith and Jones problem from a limited first person point of view—the way people all encounter the world and develop knowledge—it would go like this: Smith heard that he got the job and was surprised, but trusted that the person telling him he got the job was likely telling the truth. He looked through his pockets and found exactly 10 coins and didn’t remember taking any coins in or out of his pockets since the interview, so he thought it very likely that he had the same number earlier, too. With his new information, he had reason to believe he was mistaken earlier about Jones getting the job, but not about his belief that the person who would get the job had 10 coins in his pocket.

There’s no tricky Gettier-esque question about whether his earlier belief counted as knowledge in that case; it’s just a normal case of a person getting more information that partly contradicts his earlier understanding. There could be yet more information later: that he had a hole in his pocket and had lost an eleventh coin through it, or that someone had prank called him with the job news. In real life, there is never a point at which the final, incontrovertible truth is confirmed; there is only evidence that accrues.

The trick inside the Gettier problems is a mismatch between one use of the word “knowledge”—the kind that matches a mental thing (a belief) to a physical thing (truth) with a semi-reliable process (justification)—and another, which is more of a rhetorical flourish, and that is the way we “know” for the duration of a single fiction, that Snow White met seven dwarves. If we hear another retelling of the story in which Snow White meets six dwarves, that doesn’t contest the “knowledge” we have of the seven dwarves. It’s a briefly relevant definitional truth that only pertains within that story. When we “know” something within a story, it’s only a case of understanding a proposition from a narrator and holding it in mind for the course of the story.

If we could have equivalently certain knowledge of the world, it would have to come directly from an omniscient God, and then we would need justification for the God’s trustworthiness, ad infinitum. The narrator is the element of these problems we should be pressing harder on, rather than only Smith. The slipperiness of the mismatch between these two sources of knowledge is not an incomplete justification on Smith’s part—it’s the presence of this artificial certainty that has no real-world analog.

If we approached the Smith and Jones case like scientific knowledge, the problem with the omniscient-narrator use of the term “knowledge” is clearer. We’re more accustomed to thinking about science as a truth-sensitive process that isn’t perfectly reliable in any individual case, even if the method is observed carefully, and the results of the scientific process are held as a true-pending-other-evidence kind of knowledge. Science is not reliable, but it’s reliable enough to keep our airplanes in the sky.

If Gettier’s Smith were seen as a scientist, he would have done an experiment to confirm or deny the hypothesis “a person with 10 coins in his pocket will get the job”—and he found it confirmed. Scientific experiments don’t tell us why, and they don’t tell us how. The experiment can only confirm or deny the hypothesis. If Smith wanted to know more, he would have to conduct more experiments and try to fit the results together into an understanding of what really happened with the coins and jobs. His further experiments could test whether there are holes in any of the pockets, and whether the boss is surprised if Smith shows up on the first day of the job.

We do not describe the findings of experiments with reference to an external omniscient narrator, and to do so would be a misunderstanding of our relationship to those findings. That’s where Gettier’s examples aren’t only mismatching two unlike categories (natural and supernatural knowledge) but are actively misleading, away from a better epistemology.

If a scientist has conducted an experiment that she thinks shows rats are afraid of the color red, but the narrator says, “actually, rats are afraid of her squeaky shoes”—this does not tell us anything useful about how science is conducted. We already know that it’s a condition of all scientific knowledge that later experiments may indicate the results depended on some variable we hadn’t accounted for. We know we’re looking for a preponderance of evidence rather than an unassailable claim.

The narrator is not useful to understanding science, and is no more useful to understanding our more prosaic knowledge. Even wishing to be shown which parts of our knowledge could eventually be disproven and which couldn’t is a misunderstanding of the nature of knowledge, because we would have to subject that new information and its source to as much rigorous experimentation as we do with the data we already have.

The fact that our processes of justification aren’t completely reliable is important—but that’s not the hole into which Gettier falls, which is only the mismatch between natural and supernatural propositions.

Catherine Nichols lives in Massachusetts. Find her on Twitter @clnichols6.

This post may contain affiliate links.