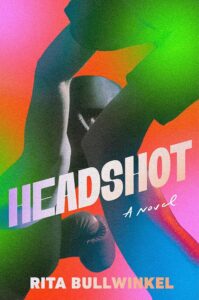

Headshot is an experimental sport novel that accomplishes what many sport novels can only dream of: it made me want to take up the sport it describes. Since reading it, I’ve begun to box.

Rita Bullwinkel renders a Daughters of America Cup national tournament with precise detail and contextualizes it within an unfathomable scope, from the original Olympic tournaments to an off-planet future. Each of the eight teenaged girl fighters in the book is treated with scrutinous care, but they are never coddled. Instead, they are entirely exposed, their redeeming qualities and their flaws equally bared. Headshot explores identity, sport, and the way our relationships and interactions with strangers—things over which we ultimately have very little control—can change our relationships with ourselves.

I feel incredibly fortunate to know Rita as a writer, mentor, and friend. In the following interview, conducted via email and collaborative google doc, we discuss underdogs, regular dogs, delusion, and of course, sport.

Hannah Lamb-Vines: I’m obsessed with Headshot. It’s like nothing I’ve ever read before! I think a lot of the surprising, exciting unfamiliarity has to do with the narrator. They’re so omniscient. They know everything, all of the characters’ pasts and presents and futures, internal states, external states, what they think of each other and themselves and the world. But the narrator also seems to have their own perspective or attitude, personality and opinions about the world and the people in this book. To me, they seem blunt and judgmental, but not cruel. Whose perspective did you feel like you were writing from for Headshot? How did you land on this all-knowing voice?

Rita Bullwinkel: Blunt and judgmental, but not cruel!! Sheesh, write it on my tombstone, Hannah, ha! I love that read on the narrator, and I think it’s true. I thought of the narrator as a Greek chorus of all the girl boxers that have come before the eight main characters in the book and all of the girl boxers that will come after. I feel like the narrator is collective and god-like in that they know all of what has ever happened in the past, and they know the molecular details of what is happening in the present, and they also know all that will ever happen in the future and when the universe will end. It was really fun to have a narrator like this. Nothing was off-limits. When I got married I requested my sister and two of my best friends, both women, read an excerpt from a poem of my choosing in unison, as a chorus. I can’t remember the excerpt. I could find it if I looked for it. The narrator is maybe them, or a collective voice that sounds like them. I love the way that words sound when they are read in unison.

“God-like” is totally how I felt about their perspective. They evoke a mythos of boxing, almost a religion, with each fight having its own afterlife. I’m thinking specifically of the description of each fighter’s world as a discus that stacks atop the fight that follows it, all the way to the ceiling of the gym. I was reminded of Deb Olin Unferth’s description of chickens’ particular spirituality in Barn 8.

Oh wow, the greatest compliment of compliments. I absolutely adore Unferth’s writing and love Barn 8 and was completely changed by those chicken spirituality sections.

One thing the narrator doesn’t know—or at least doesn’t reveal to the readers—is who will win the tournament. How much of the outcomes of the fights did you know before you started writing them? Or maybe another way of asking that question is: in what ways was writing Headshot like watching a boxing tournament?

I never knew who would win a fight while I was writing it. I found out the victor at the same time as the reader. I was always surprised by the winner. While I was writing Headshot I didn’t feel like I was watching a boxing tournament, I felt like I was fighting in it. I was trying to write from a space of inside the girls’ bodies, and inside the space of the tournament. Youth sports tournaments can have their own physics. They’re incredibly claustrophobic, spaces that can feel like space stations.

I’m so curious with every novel I read, and feel so lucky to be able to ask you since you’ve written such an extraordinary one: What was the starting point for you with Headshot? How and why did you decide to tell this story?

I have many childhood memories of the space of the sports tournament, and knew I wanted to try to write about those memories. When I remember them, it’s like looking at someone else’s life. I have great difficulty trying to figure out what I was doing there, inside the tournament. I still don’t know. That’s what started the book, and what drove it.

One of the fighters, Andi Taylor, is described as an underdog. It seems to me like a few of these fighters are underdogs, actually—maybe even all of them?—but I’m wondering what you think makes an underdog? In a story? In boxing? In life?

I think you are right that all the fighters are underdogs! I think an underdog in a story is the character that is capable of the most change. There are so many different types of underdogs in life. It’s not culturally appropriate for anyone to claim that they themselves are an underdog. People have to project the idea of underdog upon you. I suppose underdog-hood is about projection in that way. It’s about the way other people, in a given context, view you. You’ve got me realizing that there are actually a lot of dog-dogs in this book, ha!, and one fighter who thinks she is closer to being a dog than to being a girl. I’ve also always loved the word “dogged.” I also just love dogs. I am a hopeless dog person. It’s the Tony Soprano in me. I think you are too? Dogs can be desperate in a way that resonates with me. They can also be incredibly, unreasonably trusting. It doesn’t take much for most dogs to show you their belly, to roll over and say, here, look at the most vulnerable part of me.

Yeah, but whenever my dog is vulnerable like that it’s because she wants me to give her something–food or a walk or attention. As soon as she sees me seeing her belly she rolls back over and levels a look at me like a challenge. Like, “Okay, now it’s on, what are you bringing?” I guess boxing is a way to be both vulnerable and challenging, too!

I think so! I like your dog a lot. She’s wonderful.

Thanks! I think so too. All dogs are wonderful, but it’s hard not to see our own dogs as the most wonderful of them all.

Headshot is a simultaneously deeply embodied and cerebral novel, which is another reason I love it. I know you have a background as an athlete, and in an interview with Patrick Cottrell for the Paris Review you said, “I have almost no connection anymore to that part of my identity.” I’m scratching at the “almost” in that statement, and I wonder what connection does remain (or how that “almost” has changed in the six years since that interview was published), and if there’s a relationship for you between exercise or sport or physical activity and the creative process.

I look back on that past self, the self that exercised six hours a day and structured her entire life around sport and competing, that chose schools and housing because of their proximity to sports facilities and sports programs and sports equipment, and I am mystified by her, by the sheer hours she spent, not speaking, not even thinking really, just using her body for specific, very hard, highly trained things. I do have corporeal memories from those times, but when I graduated from college I kind of fell off a cliff. When I graduated, many of my teammates went on to play pro in Europe and Australia, where they have pro women’s leagues, and I, I just moved to New York and worked the graveyard shift in a windowless Anthropologie basement while I tried to find better work. I did have a self outside the sport, I had other interests. It was when I was in college that I became an obsessive reader of fiction. I like art, have pretty much always liked art, would take CalTrain from the suburb of my youth to San Francisco with frequency, so that I could see what was up at SFMOMA, The DeYoung, The Legion, The Asian Art Museum, you know, those “Great Institutions.” But sport was really where most of earth hours were funneling. It was a supremely strange way to live. Lots of authors have athletic practices, and I think that is because writers are obsessive and addictive. There is also the tradition of the flaneur, of the walker-writer. It makes sense to me that moving and writing are twinned activities.

In that characteristic blunt and judgmental voice, the narrator deems many of the fighters delusional. The delusions are less about whether or not they will win their fights than what winning—or even just fighting—means about them. I was really interested in what it means for a teenager to be delusional about their identity. Are all teenagers delusional in this way? Are all people? Do you think you held any delusions about writing this book that the narrator would call out?

I think the act of writing is an act of delusion. You have to make a fictional universe, and then make fictional people, and sit inside of all of them. I think of writing like those novelty Shakespeare productions where one person plays all the parts. You have to give over to the idea that you could be many people, that maybe you even are many people, and certainly that you used to be someone else than the person you are now. I think it’s a gradient and certain delusionals are more socially acceptable than others. Youth women’s boxing and novel writing are both barely acceptable by most people’s standards.

What were you reading while you wrote Headshot? Who would you name as the literary elders that inspired this book?

I read constantly, and can’t remember what exactly I was reading when I wrote specific parts of the book. I love the way Natalie Diaz writes about basketball, and the way that David Foster Wallace writes about tennis. Both Diaz and Wallace are interested in what it feels like to play a sport, as opposed to what it feels like to watch a sport, which resonates with me. I also really love two voice-driven books about horseback riding: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon and Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlan. Swimming Studies by Leanne Shapton is also brilliant.

What are you reading lately?

Yuri Herrera’s new book of stories, Ten Planets, is absolutely amazing. I also loved Dead in Long Beach, California by Venita Blackburn.

Are you working on anything new that you’d like to brag on?

I am working on another novel.

Finally, you may have seen that since reading Headshot I myself have ventured into the world of cardio kickboxing. I talk about it a lot on my Instagram stories. I haven’t hit anyone with my fists (yet!), but I do have a pair of gloves (loaned by an enthusiastic boxer) and a couple sets of handwraps (purchased on his insistence).

Do you have any advice for those of us whom you’ve inspired to take up the fist?

Oh wow! A tremendous compliment. Find someone to fight against who you respect, who is just as much fun to lose to as to win.

Hannah Lamb-Vines is learning to box in Berkeley, California. They edit interviews for Full Stop.

This post may contain affiliate links.