Tr. by Marina Warner

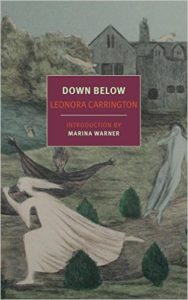

Perhaps better known as a visual artist, Leonora Carrington stands as something of a connecting thread between the older Dada and surrealism of André Breton and Max Ernst, the scene in which she emerged as an artist, and the politically-radical surrealism of Mexico, where she became associated closely with fellow-exile Remedios Varo. Carrington’s writing and art outlines a feminist take on surrealism, a movement often —rightly — considered overly-masculine. If the aggressive, often-misogynist, and homophobic masculinity of the surrealists seems more out-of-step than ever, Carrington’s writing has never felt more timely. And there is now, thankfully, a flood of Carrington’s writing newly available. The New York Review of Books edition of Down Below –— first published in 1944, in French, in the magazine VVV and out of print since the 1988 Dutton Edition — coincides with their re-release of her children’s book, Milk of Dreams, and Dorothy’s publication of her Complete Stories, all aimed to commemorate the centennial of her birth.

The publishers could not have predicted just how necessary these new editions would be right now, particularly Down Below, which narrates the author’s mental breakdown and subsequent internment in an asylum in Franco’s Spain after fleeing across the border of Nazi-occupied France. Carrington shows how social antagonisms are all routed through the female-gendered body, a process that quite literally creates a subject from such external/objective phenomena.

As Joanna Walsh writes in an excellent earlier review of the book, this experience was itself “a surrealist nightmare.” It might also be thought of as the story of the nightmare that produces surrealism, the aesthetic an unintended and perhaps unwanted by-product of radical trauma. For Carrington, the body — and its physicality, its health, mental and otherwise — stands as the primary medium for experiencing and analyzing the world. All well-and-good, and a mainstay of any feminist or queer reading of history. But particularly notable is the fact that Carrington roots this experience not just in an identity — as if that weren’t enough — but an identity rooted, and in fact trapped, within history.

Deportations, borders, identification papers, refugees, fascism — in other words, the oppressive elements of the State — are central to the book, with Carrington illustrating the way in which the state and its borders are internalized, and work directly upon the body to both pacify and sublimate it. Down Below begins immediately after her lover, the surrealist artist Max Ernst, is interred by France as an “undesirable foreigner” in the lead-up to the Nazi invasion (he was later freed, and, during the occupation, interned again by the Gestapo before escaping to New York with Peggy Guggenheim). After Ernst’s arrest, Carrington experiences a very physical sense of bodily trauma. The passage is worth quoting at length:

For twenty-four hours, I indulged in voluntary vomitings induced by drinking orange blossom water and interrupted by a short nap. . . . I know now that this was but one of the aspects of those vomitings: I had realised the injustice of society, I wanted first of all to cleanse myself, then go beyond it brutal ineptitude. My stomach was the seat of that society, but also the place in which I was united with all the elements of the earth. It was the mirror of the earth, the reflection of which is just as real as the person reflected. That mirror — my stomach — had to be rid of the thick layers of filth (the accepted formulas) in order properly, clearly, and faithfully reflect the earth; and when I say ‘the earth’ I mean of course all the earths, stars, suns in the sky and on the earth, as well as all the stars, suns, and earths of the microbes’ solar system.

The body, in this passage, becomes — in a very literal sense — the site of social antagonisms, a reflection of society, the cure for which is vicious, volatile purgings. I’ll return to this at greater length below, but here I want to propose that Carrington’s later art and writings — her surrealism — is not just the result of this purge and cleansing, but the “vomitings” themselves.

Carrington makes-literal the Kleinian concept of introjection — in which external objects are incorporated into the psyche — as all manner of social objects and institutions become embedded within her body, as when she writes: “This was the first stage of my identification with the external world. I was the car. The car had jammed because I too had was jammed between Saint-Martin and Spain.” As opposed to the male surrealists, such as Breton, who seemed to associate insanity with a form of freedom or release from the conventions of society, Carrington’s mental breakdown only brings society further into the center of the body.

It’s a torture both psychological and, later, horrifically physical. Both as a refugee in Madrid and, after, as a prisoner in the sanitarium, Carrington is subject to a battery of abuses including beatings, rape and sexual assaults, physical restraint, forced tube feedings, the implementation of “artificial abscesses,” and, most traumatic, regular Cardiozal treatments that induce seizures. Much of this violence is administered by the sanitarium physician, Dr. Luis Morales. As the narrative advances, and as more and more Cardiozal treatments are administered, the world and its objects transform into signs, symbols, and mythological avatars. The final part of the narrative finds Carrington attempting a mythical quest to get to the seat of mystical power in the hospital field house — the titular Down Below. This quest-narrative-set-within-an-institution gets a fictionalized, and fully-surreal-ized treatment, in Carrington’s later novel, The Hearing Trumpet (1976). Down Below, however, shows that the material origins of such fantastic literature lies in the violence of fascism.

Thrown through imprisonment and torture into a world of delirious fantasy, Down Below suggests the dark side of the unconscious — not as an immutable series of timeless laws and structures, but as a regressive primitivism unleashed by the violence

Certainly, this much has been said before regarding primitivism in modernist art, but Carrington shows precisely how the formation of this sense of the fantastic, the surreal, is rooted in the torture, imprisonment, and mutilation of the body. For Carrington, surrealism seems less of an art movement designed to attack the world, and more like something purged from the body, like a ball of mucous or grease on the skin after a fever.

These purgings take a form both surreal and, importantly, fantastical — and it’s important to re-locate Carrington not just as a pivotal figure of surrealism and the avant-garde, but also an important figure in the history of literature of the fantastic or, in the currently in vogue terminology, weird fiction. Indeed, Down Below has something of the structure of a Gothic novel, or its Sadean imprint, with Dr. Morales in the role as the imprisoning aristocrat and Carrington herself as the victim. Down Below can then be read as the aestheticization of life as a response to trauma — but, also, as about how art and, in particular, the genre of the fantastic, can be used to give a structure to suffering, a materialist grounding to otherwise un-acknowledgeable trauma. Science fiction novelist and theorist Samuel Delany has argued, in his critical writings, that a primary function of science fiction and speculative fiction is to bring into discourse things that are otherwise unsayable — not just new ‘scientific’ ideas and concepts but also those marginal experiences that exist in the shadows, unacknowledged and silent. Carrington’s work, then, complicates this assertion, showing the complexity and ambiguity of discourse: sometimes speaking is better thought of as being made to speak, being forced out of silence by the sheer inability to do otherwise. Down Below closes with just such a testament to the transubstantiation of trauma into meaning through art and writing, with Carrington writing that after her release from the asylum and rescue from Spain (she would travel to New York and, later, Mexico), “I was tormented by the idea that I had to paint, and when I was away from Max [Ernst] and first with Renato [Leduc, her husband for a brief time during her emigration to Mexico], I painted immediately.”

Artistic creation is, here, figured not quite as therapy, but also as another form of “torment.” We are left, then, in an ambiguous position: has her suffering given her revelation, as Breton might say, or as Gloria Orenstein, as quoted by Joanna Walsh, argues, might Carrington’s breakdown “be more accurately viewed as a breakthrough”? Despite the aesthetic development that her experiences led to, it’s not at all clear that it was ‘worth’ it. Although, that’s probably the wrong question, and not really the question Carrington poses. Rather, like the world historical events in which she is caught up, the facts are just that . . . facts, unalterable and, in some ways, resistant to being judged positively or negatively. As the cool, detached tone of Carrington’s writing suggests, they are events that happened, objective and . . . well . . . historical. Down Below can then be read as a materialist history of feminist surrealism and weird fiction, wherein écriture féminine can be seen not as an essentialist feminine trait but as a product and response to objective historical conditions. Seen from this perspective, Carrington’s fantasy feels less than fantastic, and more like the only viable realism in the face of the barbarisms of modernity.

Aaron Winslow’s novel, Jobs of the Great Misery, is available from Skeleton Man Press. His fiction, reviews, and essays have appeared in journals such as Theme Can, P-QUEUE, Smallwork, and Jacket2, among others. Additional information and writing can found at aaron-winslow.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.