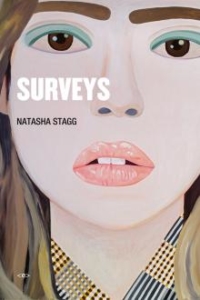

[semiotext(e); 2016]

The cover art for Natasha Stagg’s debut novel, Surveys, is a painting by Brian Calvin of a close-up view of the face of a girl. She is wearing pale blue eye makeup, her glossy lips are parted as if she has just exhaled, and her eyes are wide with an expression I could not name. Her expression could be a bit tired, a bit sad, perhaps it is a face at rest and approaching something, but more than all of these guesses, her expression felt blank to me. I could project any emotion, and her face might reflect it back.

It is this projection and recursive logic of filling in the blanks — looking to see only what you want to see — that characterizes the 23-year-old female protagonist of Surveys. Stagg traces the life of Colleen, a recent college graduate who works at a survey center in a Tucson mall. She differentiates herself from the teenagers walking by in “their neon accented phones and crap from Claire’s” and asserts: “they belonged to the mall world, and I belonged downtown” — a thought shared by almost every kid who wants to get out of the suburbs, but Colleen is driven by the dream of being desirable and loved, a dream of fame. She knows that documenting her life online and connecting with the right people will get her there. At the end of the prologue, Colleen says:

When I was legit famous, it was hard to tell when the change had occurred. It was traceable, sort of, because of the internet. . . . with the internet, it was easy to see the fame, and so everyone had to acknowledge it. If I had been born famous, the moment I would have started engaging in social media, I would have seen this fame, not the rise of it. But first I saw the low numbers, and later, the high ones.

More inviting than the retrospective narration that hooks with the desire to know more and read further is Stagg’s first-person narration: the trustworthy, subjective “I” coupled with casual language implying vulnerability and honesty very slowly reveals its shiftiness and unreliability. A present “I” in Surveys speaks more about the absence of an “I”; important events take place off the page, and we are rarely told about them firsthand from the “I” we have been primed to trust.

Chapter after chapter, we meet different people in the life of Colleen, who remains unnamed for most of the novel. For the first third of the book, we meet her coworkers: Jewelia, her boss at the survey center who does her best to report to “Corporate,” the business owners; Bryan, a focused worker who asks survey responders on dates, and who thinks “[girls] like getting hit on, no matter who it’s by”; and Frank, an obese man who can’t bring himself to lie in the office, and who continues to live with his mother. They are pressured to meet the company’s demands, even filling in surveys themselves to meet the expectations of Corporate, who are meeting the expectations of the client. The catch-22 of adaptation and prediction repeats in every character throughout the novel, creating a subtle mood of ubiquitous paranoia that foregrounds Colleen’s fixation with others’ perceptions of her.

Nightly, Colleen blogs about her admirers and gains followers rapidly, ignoring many advances online, until she comes across “semi-famous” Jim with whom she develops an intimate online relationship. They document their interactions, gain followers, and become famous almost instantly, after which she decides to move to L.A. to meet Jim:

Guy after guy after guy, and then one was this guy, this semi-famous person, who I’d seen a million times. He was this character of masculinity and reclusiveness, but since I knew all that without seeking him out, he had to be very social in order to project it. . . . I met him online, it doesn’t matter how, and we began to merge our following. Describing it would be pointless, and anyway, you can look it up. It was interaction, and people love to see that. I used a fake name so I could freely write without the burden of imagining my friends reading. . . . Together we became more famous than Jim had been alone in a matter of months. We were on buzz sites as lists, and then models played us in magazines as editorials, and then we were on buzz sites as items, but there were no photos of us together, just screen grabs of our live face-to-face chats.

Stagg doesn’t write about the content or quality of their interactions — just that “it was interaction, and people love to see that.” By doing so, she cuts off thought that may lead to aesthetic and moral judgments; what we think of as “connection,” “presence,” and “authenticity” might as well not exist as “interaction” becomes the quantified material in and of Surveys — as followers are gained and Colleen grows into a new life of fame. This is not to say that Stagg includes numbers and statistics to chart Colleen’s rise to fame. Stagg knows her strengths as a storyteller and continues to tell the story with lots of dialogue and minimal interiority instead of resorting to numbers, or to the pristine artifice of online forms such as screen-caps and chats, as done by some contemporary novelists who try hard to capture a current sensibility by directly representing and reproducing online interactions on the page.

Jim and Colleen become rich and famous, traveling across America to attend sponsored parties whose organizers pay them to use their name. Like the surveys collected by Corporate to meet the expectations of their clients, Jim and Colleen become thingified as they fall into a self-fulfilling cycle. They act according to the expectations of others in order to see an increase in followers and maintain their brand. Colleen’s fame-grounded self is thrown into question after she learns about Jim and his new lover, “Lucinda.” She hears about Jim and Lucinda’s relationship from her high school friend who hears about it via “gossip.” Colleen develops a compulsion, checking Lucinda’s blog for updates, questioning Lucinda’s worth based on people’s reactions to her, and men’s public displays of affection for her. When Lucinda makes a post about objectification, Colleen drafts an email in agreement, but criticizes her style, which she says is “like a high school teacher’s, using easy to digest examples. . . . You have a lot of good points, but the way you get people to like you with them is a little cheap.” When the need for recognition and expression is played out online, judgments are made not according to how meaningful the expression might be, but according to the amount of recognition the expression receives: the number of followers, and the social influence and popularity of people who validate the expression by paying attention in the form of a retweet or reblog.

Surveys does not follow the neat curve of the downfall of an innocent girl who tries to make it big in L.A. (I despaired when I thought Stagg would offer a Happy Christmas ending). The novel ends as Colleen says she’ll leave for Berlin to meet a guy she’s been talking with online. It’s very similar to her interaction with Jim, and despite Colleen’s preceding epiphany on Ecstasy that hints at a possibility of self-realization, the more urgent realization to me was the continuation of an earlier compulsion.

By returning full-circle, Stagg refocuses the person as an object, instead of a subject. By being a thing, the external forces of institutions — the institutions of work, marriage, family, and of monogamy and heteronormativity — become visible in the structures of social life. Surveys demands a rethinking not only of female subjectivity, or the definition of a human being as an object, but a rethinking of the social self in which the categories of “subject” and “object” are no longer enough when information and data form the material of everyday life.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji lives in Vancouver, BC where she works as an editor at Talonbooks. Her work has recently appeared in Room and Canadian Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.