[Punctum Books; 2015]

[Punctum Books; 2015]

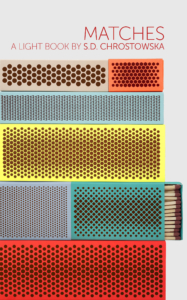

There are books that have the ability to throw your whole life into question, but these are the terms of engagement. “The mind was meant to be set ablaze, though not necessarily to survive the heat,” S.D. Chrostowska warns in the opening pages of Matches: A Light Book. A collection of essays, meditations, fragments, aphorisms, epigrams, vignettes, fables and digressions, Matches is an ambitious work of short-form philosophy, an examination of everyday life under late capitalism. Matchbooks have long been connected to literature through advertising, and Chrostowska’s words pay tribute to flame-making: “The words are matches; those that strike ignite.” These matches — which are sometimes no more than a single sentence, often just a paragraph, and just occasionally one or two pages — aim to rub up against the friction of the everyday.

Light can spread like wildfire, leaving a trail across the page, but more often, “as with damp equipment,” the flame will flicker and die, the burnt match tossed. But Chrostowska’s matchbook looks to spark thought rather than settle it conclusively. It is an interlocutor, a book to think with, through and alongside. A critique of the present in the spirit of Adorno, Nietzsche and Cioran, Matches is organized into six parts, each loosely structured around a particular set of themes: art and aesthetics; nature and technology; knowledge and power; politics and religion; history and ethics; and contemporary literary culture. Each section contains fragments made up of Chrostowska’s literary and philosophic musings on subjects as contemporary as Anonymous and Rachel Dolezal, with references ranging from Thomas Mann to Chris Marker to Francis Bacon. In these fragments, we begin to piece together a kaleidoscopic view of our cultural and intellectual landscape.

But Chrostowska’s language is slippery, and meaning is never determinate — nothing is ever solely “good” or “bad.” Ideas play against each other. Her writing does not seek to resolve the contradictions that exist beneath the surface of the everyday, but to draw them out. “Notice what has happened,” she writes in a critique of the creative industry, “creativity has replaced simple, vulgar productivity.”

The ubiquity of competitive creativity under late capitalism is, we are told, liberally rewarded. More importantly, it is not the soul-destroying work of yesteryear, but the personally fulfilling, self-realizing activity that is well worth hacking your own life to get better at.

But this is critique aimed to prod rather than persuade. Chrostowska’s tone is seductive: at once scathing and genial, cynical and sincere, it refuses to settle anywhere in between. And though she is suspicious of the way creativity has been mobilized in service to the creative industry, Chrostowska is equally quick to point out that creativity is not itself inherently valuable: “We value creativity as we value change, transformation,” she writes. But transformation is only worth celebrating if we are moving in the right direction.

It is difficult to get your footing when the ground is always shifting beneath you. This is rarely comfortable: the mind is not always meant to survive the heat. Chrostowska’s matches push us to think in ways that hurt: in the weeks I spent reading Matches I was more jittery than usual, my mind constantly reeling. I felt like I was on the edge of something, though I could not tell what that might be. I am always behaving badly, but this was different. I wanted to quarrel, I needed to question everything. Books seemed to be ruining my life. It did not help that I was also reading Auto-da-Fé during this time, Elias Canetti’s novel about a bibliomaniac scholar whose marriage to a brutish housekeeper precipitates his destruction. But I love changing my mind. And as Chrostowska writes, “Now that you have lost your faith in Literature — it does nothing for your amour proper these days — you can believe in writing.”

To read Chrostowska’s Matches is to experience a grappling against one’s own mind, to engage in the process of reading as thinking, as learning. Matches forces us into the uncomfortable territory of re-thinking our most familiar assumptions; it pushes us to turn the critical lens upon ourselves and re-examine our own lives. Here, an ethics of reading does not mean that “goodness comes bundled with books” or that “certain books should be put down for your own good.” It means beginning with yourself. Chrostowska asks not how philosophy can become praxis, but how the “becoming-praxis of philosophy [can] become its motive force, instead of an afterthought.” This is the mobilizing force behind her writing, which always challenges us to think about what lies just beyond our reach.

And so Matches is not a prescription for how to think, but an incitation that you think. Against a cultural and intellectual landscape that seeks increasingly to professionalize and instrumentalize thought, Matches carves out the space — and time — for thought outside of the programmatic. “TED talks make ideas cool, grad school makes them sexy, art makes them kinky,” Chrostowska writes. But Matches makes them circulate. Chrostowska takes ideas and puts them next to each other, so as to see how they might react — so as to test how they might combust. Hers are words to peruse and ponder rather than easily consume. I mean that this is a book to pick up and put down, and then pick up again. “Who has time for reading nowadays,” she teases. Yet Chrostowska’s tome lends itself to interruptions and quick consultations, to reading a sentence or a paragraph on the bus, or in bed before falling asleep. It is a book for the busy and easily distracted as much as it is for aficionados of the form. A challenge to contemporary reading practices, Matches resists easy summarization or classification. It is impossible to distill meaning or extract a definite message.

The only kind of resource Matches aims to become, then, is one for survival. Since we are so insistent on burning everything down, maybe in this book of ideas — which only need to be struck in order to combust — we can find a way to spark the flame. Words can illuminate the way, even if briefly, even if the flame flickers and is quick to extinguish. As Chrostowska writes, “I made this book of matches for the cold-stiff and the light-poor, with their survival at heart . . . Should my matchbook, however, fall into the hands of hot-blooded pyromaniacs who, having gone through it and finding it ‘light,’ cast it empty into the furnace of their mind, then I will fan the flames myself.”

Anna Zalokostas is a reader living on the east coast. You can find her at @azalokos.

This post may contain affiliate links.