[BookThug; 2015]

[BookThug; 2015]

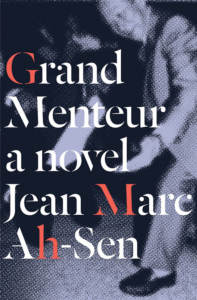

Grand Menteur, Jean Marc Ah-Sen’s debut novel, begins in Mauritius in 1956 where the father of the narrator — a young girl of imprecise age — is very senior in the Mauritian gang the Sous. Sergent Mayacou, or Serge, is the gang’s official Grand Menteur (Great Liar). Even by the time of the novel’s opening, however, much of the gang’s story is history: the first line reads, “My father used to run around in the mid-forties with a group of hustling street toughs called the ‘Sous Gang.’” This contradiction is ongoing throughout the novel: although Serge and by extension his daughter have apparently left their criminal activity behind, they are still fully tangled up in the gang’s machinations.

Serge grew up in extreme poverty, begging on the streets but dreaming of material riches. By the age of sixteen he was entirely involved in gang life and creating a reputation for himself among the thieves and liars of the underworld, although the narrator is at pains to tell us that he rarely stole. In the best tradition of the Sous Gang, each member acted according to their own particular skill, and Serge’s was lying — in particular, handling the police in the aftermath of a crime committed by other members of the gang. It’s a delicate arrangement:

They [Serge and his police contact Malbar] had kept schtum about their business with most others, allowing them to go about their business, their transactions of exchanged information, with a celebrated facility of movement. The dates for an unscheduled police training exercise could be traded for the location where stolen merchandise was being stored, or perhaps even where a fellow gang member could be nabbed for indecent behaviour; but the balance sheet constantly threatened to spill over into lopsidedness on either side.

But someone has been keeping tabs on both Malbar and Serge, recording their secrets and lies. After the first chapter, we don’t see the characters for another nine years. In 1965 Serge and his daughter are living in Brixton, in London, having been forced to leave Mauritius because of the existence of a document, the Sous Futura, that catalogues all Serge’s criminal activity. Malbar is also living in London, having received his own anonymously authored document. Serge likes to tell tales of his Sous past, hoping to impress both his daughter and their new English neighbours. The narrator worries about Serge, who is increasingly reliant on his old memories yet reluctant to do anything that might create something resembling a new life, and is increasingly dissatisfied with her own life, which involves frequent moves between England’s less picturesque locations.

She deals with all the disruption by inventing an alternative narrative: one in which her mother is well and living with them (the mother’s illness and absence are another mystery in the book), her father has safely and without repercussion extracted himself from the Sous, and they live in an extremely grand country house while the girl continues her studies. Poignantly, it’s not just the material comforts she craves: she imagines being “granted teenage heartache, pissy tantrums of the warbliest order — colours not being bright enough, wrong brands of foodstuffs, non-quality makes, and the like.”

But this narrative — the literary trope of the child of criminals or social misfits having the morals and willpower necessary to haul themselves up by the bootstraps and make good — is available only in the girl’s imagination. Despite her father’s hamfisted, overly dramatic and only partially successful attempts to rescue her, the girl never does manage to escape the influence of the Sous. In the early seventies the narrator is shipped off to Canada by herself to live with relatives she barely knows, and by 1979 she’s working at a homeless shelter in Toronto, and often secretly sleeping there herself to save money. But the past has a habit of catching up with her whenever she thinks she’s sorted her life out. When Cherelle, another Sous daughter, shows up in the shelter and reveals the narrator’s whereabouts to Serge, the girl is soon involved, against her wishes, in a massive Toronto Sous meeting at the shelter. But the gang has passed its heyday and the many members, ready to rebel, are there to cause trouble in one final Sous episode.

During the novel we are essentially as much in the dark as that narrator about the group’s activities both criminal and personal. By the end, however, she has become the Sous Grand Archiviste, and even describes herself as a “testament-taker and witness to their activities.” This is a little odd, since we never actually find out the crimes at the centre of the Sous’ activities, which makes it a gang novel without any real crime, a sort of history-lite version of gang life. How are we to interpret these past-their-best characters who seem bogged down in the minutiae of administrivia and nostalgic one-upmanship? The gang has its official titles (of which Grand Menteur is just one), and each member has his own well-guarded codex — a book of lies and alibis intended to protect him in case of capture, but somewhat short on meaty action.

This hole of what the gang actually did ties into a tricky overall structure. I’m torn between thinking it somewhat messy and unfocused, and comparing it to the dizzying effect of a merry-go-round — you can almost catch hold of images as you pass, but never fully. Deliberate disorientation is often par for the course with BookThug, a press which specialises in experimental literature and books that push boundaries, and for the greater part of the novel it nicely reflects the girl’s own position. It’s only at the end that the reader is disappointed: in a novel where so much hangs on the suspense of both reader and narrator being kept in the dark, it feels a little abrupt to discover that the girl has moved into a place of knowledge and initiation while we must stand in ignorance at the threshold, door closed.

This issue of truth and knowledge spools through the novel. The narrator can never trust her father since he is, after all, a professional liar: “Tell me, dear girl, which truth do you want? The world has not been sparing in that regard. I can give you economic truths, political truths, eternal truths even. But these will do you no good. Because, in the end, there are no Truths, and there are no Falsities.” But can we trust anything about the novel? Is it perhaps a version of one of the codices, with crimes all but written out of history so that the Sous can portray themselves as nothing more dangerous than a men’s club or secret society? Or did the narrator actually become a Sous member (we do get hints of her talent for violence and intrigue at several points), which would make this book her diary, her own codex, and therefore entirely fabricated?

Whatever the answer or answers to these questions, the real success of Grand Menteur, is the writing. The vocabulary and language are alive on the page, with sentences like “Malbar [the policeman] was an imposing fellow, hunched shoulders and an itinerant jawbone giving him the air of a constipated volcano.” In addition, the mixture of Mauritian Kreole, complete with a glossary at the back, French and English — even UK slang — adds another layer of flamboyance to the already exuberant prose. Even if the control of the ambitious, meandering structure falters a little as the novel progresses, Jean Marc Ah-Sen has written a fascinating debut.

This post may contain affiliate links.