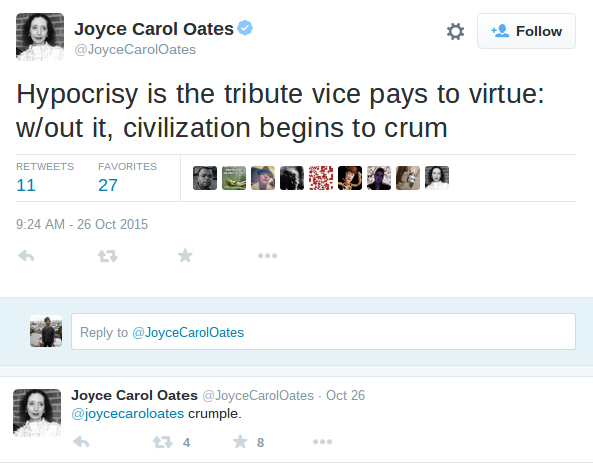

The growing number of authors who embrace social media are kicking over the final bricks in the wall between those who write books and those who read them. One glance at any 24-hour window of Joyce Carol Oates’ Twitter feed highlights this fact—and also conjures the same stupefying effect as her massive list of published works. In equal parts, she issues missives on the writing process, her political views, and cultural miscellany.

The growing number of authors who embrace social media are kicking over the final bricks in the wall between those who write books and those who read them. One glance at any 24-hour window of Joyce Carol Oates’ Twitter feed highlights this fact—and also conjures the same stupefying effect as her massive list of published works. In equal parts, she issues missives on the writing process, her political views, and cultural miscellany.

At 77 years old, Oates demonstrates a full understanding that the core challenge of modern publishing is engagement. She is emblematic of what the industry seeks out in writers: she is accessible, insightful, and most of all, present (perhaps even too present). But is it possible for her kind of rapid-fire acuity to become the cultural and industry norm? Is this what we should expect from writers from now on?

Unreachability and self-seriousness used to define many of our best-known authors, but the public appetite for writerly swagger in both old and new media is at an all-time low. Jonathan Franzen, for example, continues to spark minor firestorms with his pooh-poohing of Twitter: “I see people who ought to be spending time developing their craft […] making nothing and feeling absolutely coerced into this constant self-promotion,” he said on BBC Radio 4’s Today program.

Franzen is behind the curve, but not because he doesn’t like Twitter. It’s his fundamental misunderstanding of social media that makes his opinions so quaint. In reality, constant self-promotion is the easiest way to be ignored online. He mistakenly lumps Twitter into the sphere of added responsibility, just another chore on the long list of publicity commitments foisted upon writers who should be doing other, more culturally valuable, activities.

Because social media sites are freely accessed by anyone, it’s not uncommon for writers to worry over how widely sharing their thoughts without direct compensation could be giving away their creative insight to anyone with a passing interest. This is a cynical view, and one that’s built on the assumption that there are finite ideas in a writer’s mind and depleting them for an “RT” or a “favorite” is a self-harming exercise. Social media is not a threat to a writer’s creative development but a continuation of it—or perhaps its very beginning.

Many of Franzen’s peers subscribe to the outdated doctrine that the work speaks for itself. Until recently, the work was the only one doing the talking. Social media changed everything. Writers who still cling to the past need to consider that the public is, and has always been, primarily interested in voice, not just its products.

Teju Cole represents a new wave that isn’t making extra efforts to embrace social media, but restoring engagement as a natural responsibility of the storyteller. A 2014 profile in The Guardian described how he wasn’t afraid to start a fight on Twitter or challenge opinions he thought were out of line.

“The question could be: why are you so political?” he says. “Whereas my question would be: why aren’t you? And I think that comes from the non-American part of me which is saying that novelists in every other country, with the exception of the American or the Anglo-American sphere, actually consider it part of their work to engage.”

Like Oates, Cole enjoys a large online following. This is tied directly to his continued success in the traditional literary industry, which exists in an in-between time where physical books are still revered but consumed less.

Non-engagement with social media, or public media in any form, therefore becomes a kind of new-yet-outmoded curiosity. Elena Ferrante’s determination to remain anonymous has generated the opposite effect. The popularization of her novels in English triggered tireless public speculation about her identity. We’ve filled her absence with an ill-defined shadow that occupies more mental/cultural space than if we knew who she really was in the first place. By withholding the basic details of her life, by communicating only in written interviews through a proxy, Ferrante exhibits more than Franzenesque snobbery or a reticence for the chore of publicity. This is a full rejection of the author’s public existence beyond the printed page.

In a letter to her publisher, delivered before the publication of her first novel, Ferrante wrote, “Books, once they are written, have no need for their authors.” But the reading public, having demonstrated a declining interest in traditional publishing over the past decade, might reply with “What if our need for an author extends beyond her books?”

If a writer is to have a role in shaping what we may become in the future, then engagement with popular forums for mass communication like Twitter is crucial. Rejecting them outright can be read as a rejection of us and the promise of a digital commons. This is a risky step for a writer, and one that could lead to obsolescence.

If ever revealed, the details of Ferrante’s personal life, whether they be commonplace or extraordinary, will never quite measure up to the presence we seek from her, from anyone whose voice we value. Every author is free to choose to dismiss or embrace social media, to see it as a threat or responsibility. There are no exact rules for how to do this right. Their choice won’t alter what’s on the page, but it can absolutely flavor a reader’s experience. Those who read Ferrante will flip through her novels knowing that the author behind these words doesn’t want to be found (a mystery that can be alluring, if distracting). Teju Cole’s readers, conversely, can complete his books knowing that he’ll be there online, casting more thoughts into the void we call “the conversation.”

Voice is not a commodity but the slow accretion of individual perspective. This is a writer’s most valuable asset. Typically honed over a long period of work, a strong voice, such as that of Ta-Nehisi Coates, can galvanize people and provide tinder to a debate. With the publication of Between the World and Me, Coates established himself as a powerful figure in the discussion of racism in America. One doesn’t have to read this book to get a superficial understanding of what Coates is saying. That’s because he’s committed to engaging the culture surrounding him—whether it’s via Twitter or televised interviews or his writing in The Atlantic. Those who are intrigued or enflamed by his perspective can then go deeper into Coates’ world and read his book. There are gradations of intensity to the conversation, and that allows more people to be exposed to his contribution to it. Social media isn’t a distraction from the seriousness of what he’s published. It’s an affirmation of his argument’s importance.

Books are the ideal arena for developing deeper ideas. The public hunger for them will never go away. They are, however, just one of many possible vehicles for creative expression in our varied and complex media environment. We are not likely to see a full return to the days of unreachable geniuses whose only communication with the world arrives in long-awaited novels. And this might be a sign of progress. But it depends upon writers accepting the open invitation to join us in the space where we’ve chosen to focus so much of our attention each day.

This post may contain affiliate links.