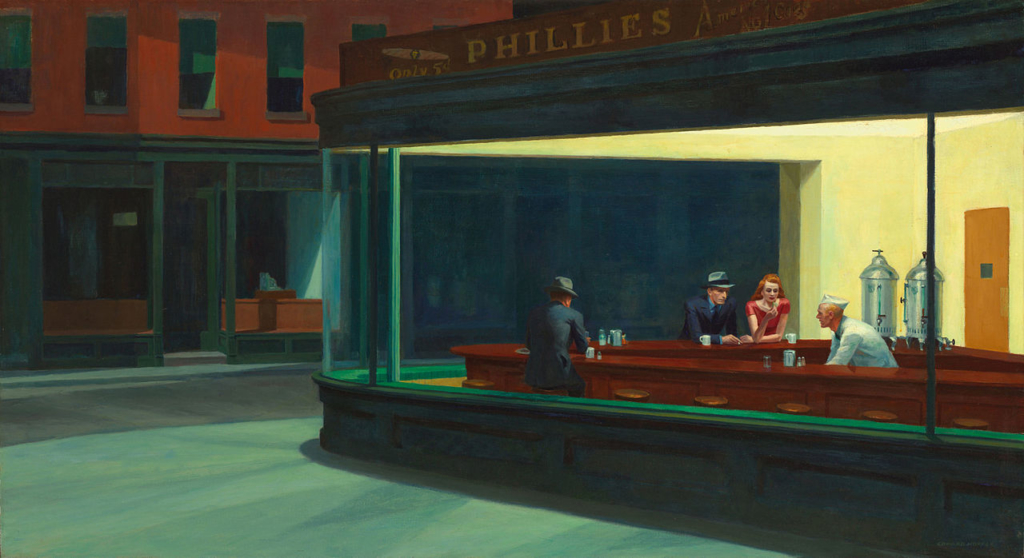

Nighthawks, by Edward Hopper, 1942.

On November 17th, 1959, three days after executing the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas, Dick Hickock and Perry Smith had lunch at the Eagle Buffet in Kansas City. According to In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s creative history of the crime, the meal included “several chicken-salad sandwiches… an untouched hamburger and a glass of root beer.” Dick eats Perry’s hamburger, then orders another. “During the past few days he’d known a hunger that nothing — three successive steaks, a dozen Hershey bars, a pound of gumdrops — seemed to interrupt. Perry on the other hand, was without appetite; he subsisted on root beer, aspirin, and cigarettes.” Despite their crimes, Dick and Perry are not inhuman killers, or so Capote leads us to believe. They are characters, flawed and rounded, antiheroes who binge or starve and whose experiences of the world correlate roughly with our own.

The fiftieth anniversary of In Cold Blood has passed with little fanfare, perhaps because the story is tired. Two men, one gun, four bodies. Variations on a theme since 1965, with a single constant: Two white men, four guns, thirteen bodies (Columbine); one white man, three guns, twelve bodies (Aurora); one white man, three guns, twenty-eight bodies (Sandy Hook); one white man, one gun, nine bodies (Charleston). Two white men, one gun, four bodies (Holcomb).

Capote subtitled his classic, “a true account of a multiple murder and its consequences.” For Capote and his readers, the phrase “multiple murder” suggested an extraordinary crime. Armed robbery taken to the limits of sanity. Although the basic components of murder in cold blood have persisted — random victims, nonsensical or accidental motives, whiteness as violence — terms like “mass shooting” and “domestic terrorism” have replaced Capote’s “multiple murder,” and rightly so. Multiple murder can be described in the language of criminal law. It may be grotesque, brutal, or unfathomable, but it does not express a political comment. The evolution of multiple murder into mass murder, mass shooting, or terrorism marks the eruption of the extraordinary crime into politics.

Jason Bell’s work has recently appeared in Guernica, Vice, The Brooklyn Quarterly, and Alimentum. He writes a monthly column for Full Stop about food and culture and lives in New Haven, CT, and St. Louis, MO.

But multiple murder, in Capote’s novel or journalism or nonfiction or whatever, does not explode into a political statement but is rather infused with a more generally American quality. In Cold Blood is committed both to the extraordinariness of the crime and the American banality (or wholesomeness) of its participants. The Clutter family and their killers are printed on two sides of the same buffalo nickel. A more accurate and disturbing way to gloss this type of crime story might then be “murder Americana.” The extremity of violence suspended against a commonplace. No battlefield but the farmhouse. The movie theater. The school. The church. The diner.

One starting point for thinking through murder Americana is Capote’s fantasy of the Eagle Buffet. In Cold Blood construes the diner as a sign of normality. And more specifically, an occasion for community that figures Dick and Perry as still part of the American social order. Still human. Yet the scene — and it is theatrical, this scene, the movement of Capote’s fly-on-the-wall, the reportorial insect observing at a distance but capturing every sentence — the scene represents Dick and Perry living within and outside of American life. Inside the diner, in Kansas City, eating chicken-salad sandwiches, unable to eat hamburgers; hunted, inhuman, sociopaths. But “American life,” in cold blood, means an artificial, universal Americana derived from the exceptionality of the murderers. Still American. Or American because they are two white men, one gun, four bodies, many chicken-salad sandwiches, an untouched hamburger.

Capote’s theory of the diner as murder Americana has itself become a cliché. Here’s a short order catalogue: Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill, and Reservoir Dogs, Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive, The Big Lebowski, Taxi Driver, Goodfellas. In all these films, the diner is the space where extraordinary crime is ordinary. Unpredictable but expected. The most extreme point on a range of American experiences, murdering and being murdered, looped into the center of Americana.

An extraordinary criminal is just like you and me, could be you or me. He eats “three successive steaks, a dozen Hershey bars, a pound of gumdrops.” By virtue of his actions, which of course follow from some inhuman flaw in his human soul, he could not be you or me. But he is always you and me, because he in part constructs the medium of violence and terror that surrounds us, is inescapable.

The meal on display in the recent film Nightingale, starring David Oyelowo, is a strong counterpoint. Peter Snowden (Oyelowo) murders his mother, maybe by accident, and spends the rest of the movie preparing an elaborate dinner for an Army buddy. Trout with walnuts. Like In Cold Blood, Nightingale uses food to establish the basic humanity of its criminal subject. His Americanity. But when the murderer is more obviously insane, a hermit locked up in his murdered mother’s home, dinner can represent an intensity of feeling unavailable to Dick and Perry. Peter’s aestheticism is at odds with murder Americana because his crime, his sensitivity, and his desires are not extraordinary or perverted. Instead, they come from his love, his trauma, his confinement, his military career, isolation, loneliness, blackness: excessively American and never American enough, he cannot assimilate into the logic of the diner. In the diner, we eat alone among others. In Nightingale, Peter eats alone.

That is why — spoiler alert — Peter kills himself rather than surrendering to police and facing the death penalty, and why Dick and Perry have the opportunity to eat the ultimate diner meal. Death row dinner, gorged or ignored. Disembodied voices of the condemned for company. “Read in the paper, afternoon paper, what they ordered for their last meal? Ordered the same menu. Shrimp. French fries. Garlic bread. Ice cream and strawberries and whipped cream. Understand Smith didn’t touch his much.”

This post may contain affiliate links.